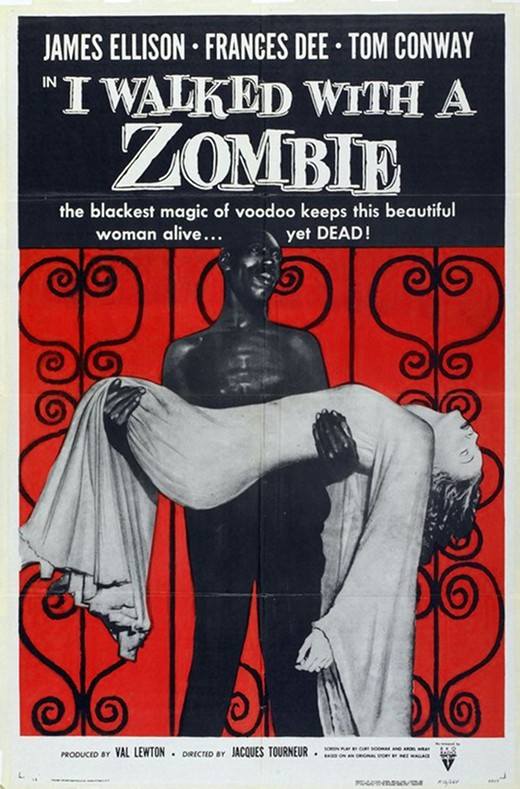

A guest post by George Lawson, Lecturer in International Relations at the London School of Economics & Political Science. He is the author of Negotiated Revolutions: The Czech Republic, South Africa and Chile, Co-Editor of The Global 1989: Continuity and Change in World Politics and has written a number of articles on historical sociology, revolution and world order. He is currently a Co-Editor of Review of International Studies and a Convener of the BISA Working Group on Historical Sociology and International Relations. He is currently working on a monograph on the anatomy of revolutions. Images by Pablo.

Daniel Drezner is no fool. This is a scholar who produces major publications, who teaches at a major institution, and who contributes to a major International Relations blog. So you have to wonder why he wrote Theories of International Politics and Zombies. Because this is, by any criteria I can come up with, a very foolish book.

Daniel Drezner is no fool. This is a scholar who produces major publications, who teaches at a major institution, and who contributes to a major International Relations blog. So you have to wonder why he wrote Theories of International Politics and Zombies. Because this is, by any criteria I can come up with, a very foolish book.

Every now and again, I come across films, music or books and wonder how, in a world where so many talented people fail to make the grade, it can be possible to create, develop, sanction and, ultimately, sell products that are so banal. Often, the answer is simple – money. Perhaps that is the case here too. But I have a feeling that something else is involved in this book as well – Drezner, and plenty of others, seem to think that the connection between zombies and IR theory is uproariously, hilariously, side-splittingly funny. Judging by much of the commentary on the book – and listening via podcast to the guffaws of the audience at a panel devoted to the book at the 2011 International Studies Association Convention – many people clearly share Drezner’s sense of humour. So perhaps I am the curmudgeon here. Because I found this book diverting only in a way popularised by a recent headline in The Onion: ‘Time Between Thing Being Amusing, Extremely Irritating Down To 4 Minutes’. I lasted about half that long with Theories of International Politics and Zombies.

Why is it that so much hoo-hah has been made about this book (10,000 copies sold within six months of publication)?

It can’t be its depth – the main text of the book runs to little more than 100 (small) pages. It can’t be its breadth – Drezner is a mainstream American political scientist who stays within conventional American debates taking place within the narrow bandwidth of the American academy. It can’t be on the basis of scholarly contribution – Drezner’s book neither carries the élan of work exploring the links between IR and popular culture, like Jutta Weldes et al.’s To Seek Out New Worlds: Exploring Links Between Science Fiction and World Politics, nor does it deliver a considered treatment of the ways in which zombie rituals provide insights into many of the world’s cosmologies. And it can’t be the argument, because the book doesn’t have one. Drezner merely runs through the analysis and predictions provided by what he considers to be the main theoretical approaches in IR (realism, liberalism, neo-conservatism and constructivism, with a passing nod to ‘second image’ approaches and bureaucratic politics, plus a brief section on prospect theory) if the world was faced with a zombie attack. The closest Drezner gets to making a serious point is when he spends a single paragraph arguing that current IR theories are too state-centric when it comes to assessing security threats.

So perhaps, as the ISA panel appears to demonstrate, the popularity of Zombies stems from its comedy? Well, here are (some of) the gags: ‘To paraphrase Thucydides, the realpolitik of zombies is that the strong will do what they can, and the weak must suffer devouring by reanimated, ravenous corpses’ (p. 38); ‘In the end, realists would caution human governments against expending significant amounts of blood and treasure to engage in far-flung anti-zombie adventures – particularly blood’ (p. 43); ‘To paraphrase Robert Kagan, humans are from Earth and zombies are from Hell … The zombies hate us for our freedoms – specifically, our freedom to abstain from eating human flesh’ (p. 62-3); ‘A risky but intriguing policy option would be for human governments to use psychological operatives to engage in “cognitive infiltration” of the undead community … Through suggestive grunting and moaning, perhaps these operatives could end the epistemic closure among zombies and get them to question their ontological assumptions’. (p. 107); ‘A specter is coming to haunt world politics – the specter of reanimated corpses coming to feast on people’s brains’ (p. 109).

So perhaps, as the ISA panel appears to demonstrate, the popularity of Zombies stems from its comedy? Well, here are (some of) the gags: ‘To paraphrase Thucydides, the realpolitik of zombies is that the strong will do what they can, and the weak must suffer devouring by reanimated, ravenous corpses’ (p. 38); ‘In the end, realists would caution human governments against expending significant amounts of blood and treasure to engage in far-flung anti-zombie adventures – particularly blood’ (p. 43); ‘To paraphrase Robert Kagan, humans are from Earth and zombies are from Hell … The zombies hate us for our freedoms – specifically, our freedom to abstain from eating human flesh’ (p. 62-3); ‘A risky but intriguing policy option would be for human governments to use psychological operatives to engage in “cognitive infiltration” of the undead community … Through suggestive grunting and moaning, perhaps these operatives could end the epistemic closure among zombies and get them to question their ontological assumptions’. (p. 107); ‘A specter is coming to haunt world politics – the specter of reanimated corpses coming to feast on people’s brains’ (p. 109).

Is this funny? I guess so. But surely only in a Beavis and Butthead kind of way. However, regardless of whether or not people find Drezner amusing, there is a serious issue at work here: Theories of International Politics and Zombies falls into the well-worn trap of using popular culture as a faddish way to popularize the claims of existing theories. It is difficult to see how the book offers much beyond a shallow translation of ‘high’ theory to ‘low’ culture. As others have pointed out, Drezner’s ‘in the box’ approach regurgitates IR’s tradition of apocalyptic thinking in a way which asks no new questions, breaks no new ground and works to reinforce existing hierarchies in the discipline. At its best, the use of popular culture and fiction does exactly the opposite of this: questioning taken-for-granted assumptions about world politics; transgressing existing boundaries; and opening up the discipline to utopian and dystopian thinking, counterfactual analysis, and cultural encounters which otherwise go unproblematized.

Kafka, Huxley and Orwell used speculative work to highlight complex political issues which went unaddressed by standard genres. The best academic work in this field does this too, using non-traditional themes and issues as imaginative sources by which to open up fields of enquiry. Michael Shapiro, Cynthia Weber, Jutta Weldes, Iver Neumann, China Miéville and others focus on big, important issues: power and the production of knowledge; identity and representation; the blurriness of reality and fiction. In contrast, Drezner’s book serves up the same old stories, told by the same old theories. By the end of the book, I was not even sure how much he knew about zombies, at least not beyond the recent vogue for Anglo-American books and films on the subject.

All in all, therefore, Zombies appears less an exercise in fertile intellectual exploration than a belated realization by mainstream scholars that there is something interesting – and profitable – in more radical approaches to world politics. When you think about it that way, books like Theories of International Politics and Zombies are neither clever nor funny; they are the academic equivalent of playground envy. And if this is the current state-of-play in IR, then I, for one, find it all just a wee bit depressing.

Great post, George. I find myself in wide agreement with it and particularly with the point that the issue is not one of policing the material which ‘proper’ IR scholars should or should not engage with but of the individual intellectual merits of such forays into fiction and popular culture. Where these are the conduit for trite restatements of IR doxa peppered with cheap laughs, the merits seem very questionable.

As for the motivations, financial reward may indeed be an incentive (although perhaps more so for the similar themed books it will inevitably spawn than for this one, the publishing success of Drezner’s book probably exceeding his own expectations by quite a margin) but a lot of its manifest appeal seems to be the knowing self-indulgence of IR scholars for their inner geek.

In the final instance though, what concerns me perhaps most of all is that, pitched at least in part at an introductory undergraduate level, ‘Theories of International Politics and Zombies’ seems to amount to a pandering to popular culture in order to make IR ‘cool’ or ‘relevant’ to a generation of learners presumed to be too engrossed in a diet of Hollywood films and Internet memes to find international politics interesting in its own right. While it is no doubt healthy for IR academics to interrogate the way in which the discipline is taught and to be sensitive to the needs of their students, the notion that students learn best when entertained and engaged within the familiar confines of their cultural zeitgeist seems to express a loss of faith in the discipline’s own worth and a further abdication to a consumerist model of higher education.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Living Dead: On the Strange Persistence of Zombie International Relations « The Disorder Of Things | #OCCUPYIRTHEORY

Pingback: The Return of IR and Zombies (the straight to dvd sequel) « Chaos and Governance