Roots, Radicals, Rockers and Reggae by Stiff Little Fingers

And lest we forget the roots, here’s the original:

And lest we forget the roots, here’s the original:

Men cannot live without seeking to describe and explain the universe to themselves. The models they use in doing this must deeply affect their lives, not least when they are unconscious; much of the misery and frustration of men is due to the mechanical or unconscious, as well as deliberate, application of models where they do not work… The goal of philosophy is always the same, to assist men to understand themselves and thus operate in the open, and not wildly, in the dark.

-Isaiah Berlin, The Purpose of Philosophy

Last month I presented two papers on human rights at the ISA conference in Montreal (both are available in draft form from the ISA website, here and here, please do not cite, but comments are welcome). Attempting to offer a summary of those papers, however, has made clear to me that they are importantly connected and perhaps incomplete as separate papers – hence the “should” in the title. Together, the papers offer a pluralistic and agonistic reconstruction of human rights as a political concept and an ethical ideal. I’ll try to offer a shorter version of the argument that connects these two papers here, though broken into three (relatively) short posts. My reconstruction begins (Part 1) with a theoretical analysis of human rights, which forms the basis for an argument (Part 2) about how we should understand the history of human rights and, finally, (Part 3) leads to a defence of a democratising reconstruction of human rights.

The Nature of Human Rights Claims

Human rights, I argue, are of central importance for contemporary political theory because they respond to the basic question of legitimate authority, which is most simply the question of what justifies the coercive power of political authority. Traditionally, the question of legitimate authority addressed to the modern state and it is from this line of thinking that we inherent the rights discourse – in which authority is rendered legitimate by protecting the rights of individual members of the political community, which is a group importantly distinct from those actually subject to the coercive power of the state.

The details of this can be filled-in in many ways, but the logic of rights is central to modern political thought. These political rights, and the institutions of governance they support, in turn, are justified by an appeal to moral rights. The moral appeal is central to the rights tradition as it is the absolute and certain quality of moral principles that justify the limitations imposed upon political authority and the powers granted to political authority to exclude, harm and constrain. Human rights emerge from this modern rights tradition, but the conditions and consequence of their emergence are complex. Continue reading

Ending is such sweet sorrow. Yesterday the alphabet series over at Bad Reputation came to a close. Its task: “..to address (with reasonable neutrality), the make-up of the English mother-tongue, to consider how the language has evolved over the centuries, and in the process to prompt some questions about how gender issues are woven into the fabric of the language we use everyday.”

Ending is such sweet sorrow. Yesterday the alphabet series over at Bad Reputation came to a close. Its task: “..to address (with reasonable neutrality), the make-up of the English mother-tongue, to consider how the language has evolved over the centuries, and in the process to prompt some questions about how gender issues are woven into the fabric of the language we use everyday.”

And what an unravelling it was. Here are some disordered excerpts. Direct your thanks at Hodge.

Z is for Zone:

The Medieval West was not to be left behind in all this sexy-talk: no right-thinking female of the thirteen-hundreds considered herself fully sexed-up without a gipon, a type of corset designed to flatten the breasts and emphasise the stomach. And in case this proved insufficient, she might also pad her belly out for extra effect – well-rounded bellies appear again and again in contemporary art – and, as with the Cranach Venus, a decorative zone was the perfect way to emphasise its shape, making this a garment no less sexually charged in the 1340s than the 1940s (when, of course, its job was to hold the belly in). Like a garter, then, a girdle could serve as a fetishistic focal point for erotic (and indeed erogenous) zones, marking them out and keeping them restrained at the same time.

H is for Hysteria:

One explanation for [Hysteria’s] seeming explosion during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is its use as a catch-all term for Generic Women’s Troubles (hence calling it, essentially, ‘womb-problem’), and indeed, it does seem to have been partially conflated with chlorosis (a type of anaemia), which is perhaps better known to Renaissance drama fans as ‘green sickness’. Thus, in John Ford’s play ‘Tis Pity She’s A Whore (you’d think you couldn’t top that title, wouldn’t you?) Annabella is thought to be suffering from ‘an overflux of youth’, in which case ‘there is no such present remedy as present marriage’. Translation: get a willy in her, quick.

The presentation I gave at the International Studies Association (ISA) conference was on the broad topic of technology and world politics, with more specific reference to the use of crisis mapping software in humanitarian situations. One of the main contentions of this research is that the role of technology in world politics tends to get massively overlooked by the field of IR. This is a bit odd considering the important role of technology in issues of world politics – weapons systems, financial systems, communications systems, surveillance technologies, social media tools, etc., etc. In fact, it’s hard to point to a single standard IR issue that isn’t infected with technological aspects. Yet IR remains a science limited to a focus on disembodied individuals. Whether it be rationalists or constructivists, little mention needs to be made of the actual materiality of these actors and their contexts. Instead, international relations is taken to be comprised of these actors alone.

To get a sense of the materiality of the world, you have to turn to alternative fields – political psychology and its attention to our embodied nature; gender studies for focus on the body and its political roles; and in my particular case, science and technology studies (STS) for an understanding of technology’s unique form of agency. Growing out of sociology, STS became known originally for taking a specifically social approach to the study of science. That is to say, it began looking at how scientists operate in practice in order to create facts. In doing so, it created a lot of controversy – first, for its willingness to suspend the truth of scientific claims in order to look purely at how they gain legitimacy. Second, for its undermining of naïve visions of the scientific method (a naivety that plagues IR to this day). Finally – and for the purposes here, the most interesting controversy – was the agency it attributed to nonhuman objects. I won’t go into the nuances here (maybe another time), but the basic point here is that agency is not primarily about intentional action (a problematic claim about human agency anyways), but instead it is about action changing a structural context. [1] In this sense, it seems unproblematic to agree that technical objects do have agency – in other words, they can change structural contexts by being introduced into preexisting assemblages (a term which itself points to the mutual implication of technology and society).

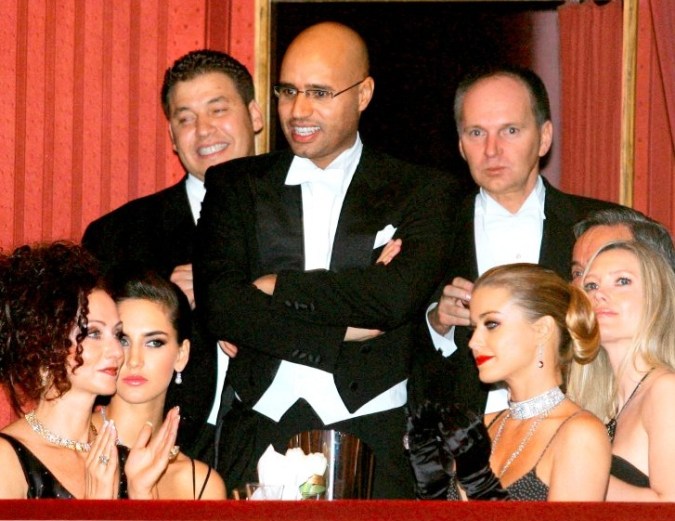

You might have thought that the realities of muscular interventionism in Libya had by now trumped the apologetics of constructive engagement. But Benjamin Barber has other ideas. His counter-attack to the nay-sayers deploys several connected themes, all of which appeal, once again, to the purported political realism of befriending Saif Gaddafi and the corresponding idealism and naivety of opposing such benevolent stewardship.

First, the attacks on the fortunate son have been “overwrought”, and have materially endangered the chances of peace by pissing him off. Second, Saif remains “a man divided, torn between years of work on behalf of genuine reform that at times put him at risk”, and thus still open to our charms. Third, he is even now working for civil society and democracy, pressuring his father to release journalists and in effect continuing the work of his foundation as a fifth column within the regime. Yes, Saif has been naughty (I’m not angry, I’m just disappointed), but his intentions are still at least partly good, and failure to achieve a better Libya through a rapprochement with him ultimately condemns we who would rather cling to the saddle of our high-horse than descend into the messy realities of progress.

The riposte is bold, and at least has the merit of maintaining the original analysis, no matter how much short-term developments may seem to degrade it. But the rationalisation, wrapped in what Anthony Barnett so aptly characterises as a ‘cult of sincerity’, falls somewhat short. The central meme, repeated by David Held, represents Saif Gaddafi as an enforcer-cum-reformer of near schizophrenic proportions. While it is (now) readily admitted that he is personally responsible for human wrongs, it also becomes necessary to insist on his internal, and magnificently cloaked, commitment to human rights. This may work for those who knew him personally and remain invested in his personal quirks and charms, but can hardly stand as a recommendation for his role as good faith mediator. As Barber himself argues (with a different intent and a suspect logic) if Saif is both revolution and reaction then he is also neither, and therefore a cipher for the projection of political fantasies.

These justifications repeat binaries of politics/morality and realism/idealism in dismissing critics (we were engaged in a calculated politics while you luxuriate in abstract ethics). Yet they also almost attempt, ham-fisted and inchoate, to escape them. After all, the defence is not that Saif is merely our bastard. Nor is it that he is a true rebel son, prepared to overthrow not only the personal dynamic of filial submission but also the political fatherhood of little green books, torture prisons and outré couture. He is said to be both, flickering and indistinct, as if this commends him. As if he can only change things because he is the natural heir of the old order. He moves between our worlds, you see. A Venn-diagrammed endorsement.

UPDATE (19 April): I’ve just received confirmation that a proposal based on this Symposium has been accepted as a Special Issue for the International Feminist Journal of Politics. All papers will be peer-reviewed. Papers not presented at the Symposium will not only be welcome but are actively encouraged. The deadline for first drafts is likely to be in August 2011 for eventual publication in 2012. Further details to follow…

A call for participation in a one-day Symposium at LSE I’ve been involved in organising. It’s taking place in just over three weeks and promises to be very productive and, yes, exciting. Thanks to some funding, places are free, but do email me if you want to come so we can get a sense of numbers for food. There will also doubtless be continuing discussion afterwards. Please distribute widely.

Thursday 5 May 2011

Thursday 5 May 2011Room Clem.D702, Clement House (on Aldwych), London School of Economics & Political Science

Keynote: Professor Cynthia Cockburn (City University and University of Warwick)

Sponsored by the British International Studies Association Gender IR Working Group, the LSE Department of International Relations and the LSE Gender Institute.

Thinking about masculinity, maleness and men has always had a place in the interdisciplinary fields of feminist, queer and gender studies. Discussion and debate about the relevance of masculinity as a shifting concept has recently been further developed in the fields of politics and International Relations (IR) where scholars have explicitly tried to address women’s experiences in relation to the persistence of the ‘man question’.

Despite this, masculinity in international politics remains somewhat amorphous. Research has tended to be disconnected, addressing particular wars or media events, rather than masculinity as an organising concept or its role across space and time in its historically variable forms. This symposium (and a proposed journal Special Issue arising from it) therefore seeks to extend and deepen work on the conceptual character and concrete forms taken by masculinity through the lens of violence and conflict settings.

“I saw folk die of hunger in Cape Verde and I saw folk die from flogging in Guiné (with beatings, kicks, forced labour), you understand? This is the entire reason for my revolt.”.[1]

I sincerely believe that a subjective experience can be understood by others; and it would give me no pleasure to announce that the black problem is my problem and mine alone and that it is up to me to study it…Physically and affectively. I have not wished to be objective. Besides, that would be dishonest: It is not possible for me to be objective.”.[2]

For some time, I have been preoccupied by the connections between the ways in which we see, analyse and interpret the world, and the forms of political action to which this gives rise. In general, for critical social theory, the challenge is how to think about the world such as to understand and overcome structures of injustice or violence in it. As a particular instance of this, the anti-colonial movement of the middle part of the twentieth century provides much food for thought, not least when so many point to patterns of colonialism and imperialism in world politics today.

In the paper I presented to the International Studies Association conference a few weeks ago, I offer a particular reading of Frantz Fanon and Amílcar Cabral as philosophers of being, knowledge and ethics. Commonly, but not exclusively, these two figures are understood as having important things to say about revolt and resistance – Cabral is portrayed as the arch-pragmatist who emphasises the need for political unity and realistic objectives, whereas Fanon is frequently engaged for his affirmative treatment of violence in an anti-colonial context. In this sense, they are largely approached as political thinkers and activists rather than philosophers per se.

Yet, their systems of thought stem from distinctive, and in important ways shared, philosophical commitments on the nature of being (ontology), ways of constructing knowledge (epistemology) and the ethical foundations of engagement (um, ethics). These foundations are strong, coherent and compelling points of departure and important in terms of understanding what kind of future order they envisaged. What are these, and how do they support an anti-colonial political programme? What is the relevance of this intellectual legacy today? Continue reading

In amongst a typically judicious review of Treasure Islands and Winner-Take-All Politics, David Runciman draws a suggestive comparison between the contemporary politics of financial ‘mobility’ and the legacy of colonialism.

In amongst a typically judicious review of Treasure Islands and Winner-Take-All Politics, David Runciman draws a suggestive comparison between the contemporary politics of financial ‘mobility’ and the legacy of colonialism.

Shaxson’s book explains how and why London became the centre of what he calls a ‘spider’s web’ of offshore activities (and in the process such a comfortable home for the likes of Saif Gaddafi). It is because offshore is the offshoot of an empire in decline. It perfectly suited a country with the appearance of grandeur and traditionally high standards, but underneath it all a reek of desperation and the pressing need for more cash.

As Shaxson shows, many of the world’s most successful tax havens are former or current British imperial outposts…What such places offer are limited or non-existent tax regimes, extremely lax regulation, weak local politics, but plenty of the trappings of respectability and democratic accountability. Depositors are happiest putting their money in locations that have the feel of a major jurisdiction like Britain without actually being subject to British rules and regulations (or British tax rates)…

…The other thing most of these places have in common is that they are islands. Islands make good tax havens, and not simply because they can cut themselves off from the demands of mainland politics. It is also because they are often tight-knit communities, in which everyone knows what’s going on but no one wants to speak out for fear of ostracism. These ‘goldfish bowls’, as Shaxson calls them, suit the offshore mindset, because they are seemingly transparent: you can see all the way through – it’s just that when you look there’s nothing there.

In some senses this confirms an established story. Imperialism 101. For others, it will unsettle the idea of globalisation and inter-dependence as essentially the negation of great power politics.

Saif Gaddafi (PhD, LSE, 2008) has lost a lot of friends recently. Even Mariah Carey is embarrassed by him now. The institution to which I have some personal and professional attachment is implicated in a number of intellectual crimes and misdemeanours, as may be a swathe of research on democracy itself. Investigations are under way, by bodies both official and unofficial. All of this now feels faintly old-hat (how much has happened in the last month?), even rather distasteful given the high politics and national destinies currently in the balance. So let the defence be pre-emptive: the academy has political uses, and those with some stake in it need feel no shame in discussing that. If crises are to be opportunities, let us at least attempt to respond to them with clarity and coherence. After all, our efforts are much more likely to matter here than in self-serving postures as the shapers of global destiny.

Saif’s academic predicament is both a substantive issue in its own right and a symptom. As substance, there is now a conversation of sorts around complicity and blame. Over the last weeks, David Held has appealed for calm and attempted a fuller justification of his mentorship (Held was not the thesis supervisor and Saif was not even a research student in his Department at the time, although he, um, “met with him every two or three months, sometimes more frequently, as I would with any PhD student who came to me for advice”). Most fundamentally, it was not naivety but a cautious realism based on material evidence that led a pre-eminent theorist of democracy to enter into what we could not unreasonably call ‘constructive engagement’. [1]

Held characterises the resistance of Fred Halliday to all this as reflecting his view that “in essence, [Saif] was always just a Gaddafi”, which of course makes him sound like someone in thrall to a geneticist theory of dictatorship. The actual objection was somewhat more measured, and, if only ‘in retrospect’, entirely astute:

Today the Arts & Humanities Research Council responded to yesterday’s piece in The Observer claiming that the government had readjusted the rules (specifically The Haldane Principle) to increase their control over the direction of research in the UK within the state’s ‘national priorities’. Shorter version: the Tories didn’t pressure us, we’re completely independent and the funding to ‘The Big Society’ is coincedental.

Today the Arts & Humanities Research Council responded to yesterday’s piece in The Observer claiming that the government had readjusted the rules (specifically The Haldane Principle) to increase their control over the direction of research in the UK within the state’s ‘national priorities’. Shorter version: the Tories didn’t pressure us, we’re completely independent and the funding to ‘The Big Society’ is coincedental.

Iain Pears is on the case. As he notes, it’s simply not convincing that the approved language suddenly appeared in the relevant documents unconnected with the political agenda of the governing party. The pressure may have been implicit, and the relationship might have been more informal and complicit than hierarchical, but the consequences for research are much the same.

But the AHRC not only wants to defend itself from these specific charges but also to maintain the legitimacy of the government setting overall priorities. Once again, the exact mechanics are expected to be taken on trust. Indeed, in 2009 a Commons Select Committee (Innovation, Universities, Science and Skills, since you asked) addressed this exact point. While agreeing ‘in theory’ that the government had a role in setting overarching strategy, the relevant MPs (hardly a selection of Parliamentary rebels) put their collective figure on the aspects of policy that still concern us most: