Monday 17 January marked the official US holiday honoring Martin Luther King, Jr. While watching Monday’s Democracy Now! program, featuring substantive excerpts from King’s speeches, the clarity with which he connected the domestic fight for equality to international politics, in particular poverty and war, struck me. The international aspects of King’s thinking, I believe, are important for two reasons.

King’s Radicalism

First, it challenges the interpretation of King as an insufficiently radical leader offered by some critics, and the co-option of King’s legacy not only by “moderate” liberals but also by conservative political figures in the US. King has become a symbol in the public consciousness of a safe reformism and a favorite icon for the type of liberal who abhors radicalism above any other political sin. As Michael Eric Dyson says, “Thus King becomes a convenient icon shaped in our own distorted political images. He is fashioned to deflect our fears and fulfill our fantasies. King has been made into a metaphor of our hunger for heroes who cheer us up more than they challenge or change us.”

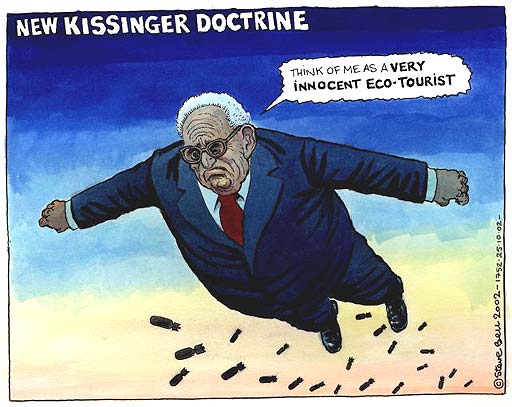

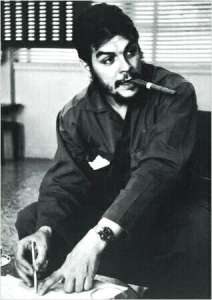

A personal anecdote to illustrate the point: a couple of years ago while handing over the editorship of Millennium to the incoming editorial team, one of the new editors commented on the large poster of Che Guevara that hangs on the Millennium office door. The Che poster, so far as I know, predates most of us currently associated with the journal, therefore I suggested it should stay. I then asked why Che should go. My colleague suggested that Che’s participation in revolutionary violence made him an inappropriate icon – in many academic disciplines this might be a rather devastating point, but International Relations is full of characters far more violent and less admirable than Comrade Che – see Paul’s post on Kissinger, for example.

When asked who might better grace the walls of the office my colleague suggested Martin King or Mohandas Gandhi (a political figure subject to a similar post-hoc liberal deification), with their key qualification as acceptable iconography being that they had not participated in political violence. While I have a great deal of sympathy for non-violence, my own introduction to both King and Gandhi came through the study of non-violence political strategy, the liberal (and I think my colleague would gladly accept that identification) embrace of King or Gandhi, paired with the repudiation of Che, is (unintentionally?) disingenuous.

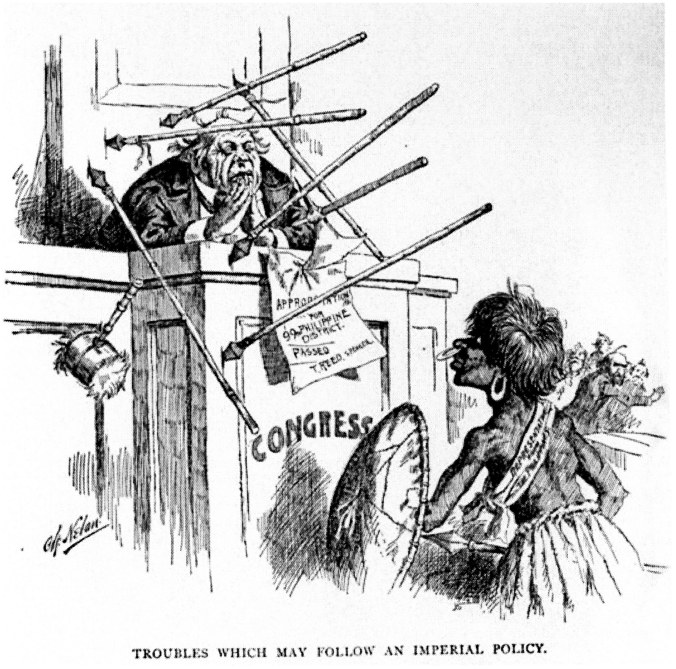

It’s a disingenuous embrace because it insists that the first rule of acceptable political action is a renunciation of physical violence, while at the same time turning a blind eye to the violence institutionalized in the state through everyday police brutality and legalized/legitimized imperial warfare, as well as the structural violence inherent to global capitalism. This misses the radical content of non-violence as practiced by King and obscures the link that exists between non-violent agitation and armed resistance. The political commitments and motivations of King and Che are remarkably similar, even as their fundamental orientations (Marxism vs. Christianity) and tactics (non-violent direct action vs. guerrilla insurgency) diverged. Continue reading