A trailer for my next post about The Roots

Taken from Phrenology – featuring lyrics by Amiri Baraka, music by The Roots and the unofficial and strangely charming video by a local Philadelphia film maker, Bryan Green. More on this album to come…

A trailer for my next post about The Roots

Taken from Phrenology – featuring lyrics by Amiri Baraka, music by The Roots and the unofficial and strangely charming video by a local Philadelphia film maker, Bryan Green. More on this album to come…

UPDATE (10 March): Material is coming thick and fast on #Kony2012, so I’m adding three recent interventions. The first is from Ismael Beah, he of child soldier fame, on CNN (apologies for the awful interviewer).

The second is from Adam Branch (who just has a book out on Uganda, war and intervention) on the wrongness, and also the irrelevance to Northern Ugandans, of Invisible Children:

My frustration with the group has largely reflected the concerns expressed so eloquently by those individuals who have been willing to bring the fury of Invisible Children’s true believers down upon themselves in order to point out what is wrong with this group’s approach: the warmongering, the self-indulgence, the commercialization, the reductive and one-sided story it tells, its portrayal of Africans as helpless children in need of rescue by white Americans, and the fact that civilians in Uganda and Central Africa may have to pay a steep price in their own lives so that a lot of young Americans can feel good about themselves, and a few can make good money. This, of course, is sickening, and I think that Kony 2012 is a case of Invisible Children having finally gone too far. They are now facing a backlash from people of conscience who refuse to abandon their capacity to think for themselves.

The third, from Teddy Ruge, beautiful in its rage:

This IC campaign is a perfect example of how fund-sucking NGO’s survive. “Raising awareness” (as vapid an exercise as it is) on the level that IC does, costs money. Loads and loads of money. Someone has to pay for the executive staff, fancy offices, and well, that 30-minute grand-savior, self-crowning exercise in ego stroking—in HD—wasn’t free. In all this kerfuffle, I am afraid everyone is missing the true aim of IC’s brilliant marketing strategy. They are not selling justice, democracy, or restoration of anyone’s dignity. This is a self-aware machine that must continually find a reason to be relevant. They are, in actuality, selling themselves as the issue, as the subject, as the panacea for everything that ails me as the agency-devoid African. All I have to do is show up in my broken English, look pathetic and wanting. You, my dear social media savvy click-activist, will shed a tear, exhaust Facebook’s like button, mobilize your cadre of equally ill-uninformed netizens to throw money at the problem.

Cause, you know, that works so well in the first world.

Glenna Gordon‘s 2008 image of the Invisible Children founders in cod-Rambo pose with the Sudan People’s Liberation Army now defines the #Kony2012 backlash. Jason ‘Radical’ Russell – he who speaks excitedly of ‘war rooms’ – and his compatriots have thus far notched up 12 million-odd Vimeo hits and over 32 million YouTube hits with their 30-minute hymn to awareness, social media, atrocity prevention and youth power. A simulacrum of solidarity now not quite besieged, but at least peppered, by an array of critiques and counter-points, almost always from scholars and activists with their own well-established records of engagement and internationalism.

That backlash is now, predictably enough, giving rise to a counter-backlash from newly enlivened global citizens, and the predominant form taken by this response is itself instructive. Comment threads on posts like Mark’s consistently reveal a nascent activist consciousness which is hugely fragile, but also aggressive. Although many presumably did not know of Joseph Kony until this week (and in this minimal sense, #Kony2012 clearly ‘worked’), they are now so outraged at even the hint of complexity or counter-point that they denounce others as self-promoters, ignorami (ignoramuses?), complacent and/or complicit (by some unspecified metric) in human suffering. The juxtaposition is telling: the fresh anger and one-dimensional vigour of discovering atrocity and of being “empowered” (however vaguely) to end it is simply too appealing to withstand reasoned discussion. And so newly-minted ‘doers’ find themselves in the position of having to attack those old established ‘cynics’, Ugandans and Uganda hands among them, in whose very name they “won’t stop”. Say, at what point exactly did common humanity come to mean lecturing Ugandans that they were “ungrateful” and “negative” for pointing out that Museveni is not so nice either?

But what has been the content of this unbearable counter-critique? Continue reading

The second of us to achieve doctorhood since the inception of The Disorder Of Things, our very own Roberto this afternoon survived interrogation by Charles Tripp and Toby Dodge to become a fully certified Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations. His thesis being entitled Gramsci in Cairo: Neoliberal Authoritarianism, Passive Revolution and Failed Hegemony in Mubarak’s Egypt, 1991-2010. Timely and on trend, awarded sans corrections.

In lieu of a substantive post, some bits worth reading on the broad theme of inequality.

Andrew Hacker, “We’re More Unequal Than You Think”

China Miéville, “Oh, London, You Drama Queen”

Ari Berman, “The 0.000063% Election”

John Bingham, “Upper Classes More Likely to Cheat”

David Wong, “6 Things Rich People Need to Stop Saying”

The Onion, “Cost of Living Now Outweighs Benefits“

This is a continuation of my previous post…

Who Are Human Rights For?

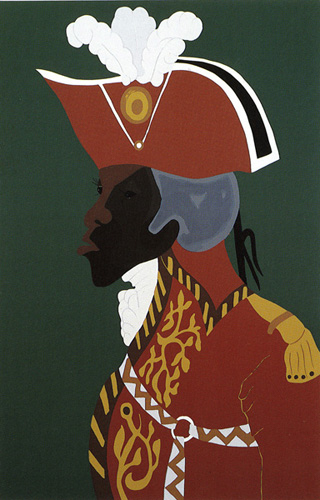

All of the authors take account of the ambiguous history of human rights, in which they can be said to have inspired the Haitian, American and French revolutions, while also justifying the counterrevolutionary post-Cold War order dominated by the United States. Yet recognising this ambiguity without also acknowledging the distinctive reconstruction of contemporary human rights that makes them part of a neo-liberal international order and the unequal power that makes such a quasi-imperial order possible would be irresponsible. A primary contribution made collectively by these texts is that they clearly diagnose the way human rights have been used to consolidate a particular form of political and economic order while undercutting the need for, much less justification of, revolutionary violence. Williams says of Amnesty International’s prisoners of conscience, who serve as archetypal victims of human rights abuse,

the prisoner of conscience, through its restrictive conditions, performs a critical diminution of what constitutes “the political.” The concept not only works to banish from recognition those who resort to or advocate violence, but at the same time it works to efface the very historical conditions that might come to serve as justifications – political and moral – for the taking up of arms.

Human rights, then, are for the civilised victims of the world, those abused by excessive state power, by anomalous states that have not been liberalised – they are not for dangerous radicals seeking to upset the social order.

This post (presented in two parts) is drawn from a review article that will be forthcoming in The Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, which looks at a recent set of critical writings on human rights in order to consider the profound limitations and evocative possibilities of the contested idea and politics of human rights.

Human Rights in a Posthuman World: Critical Essays by Upendra Baxi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Surrendering to Utopia: An Anthropology of Human Rights by Mark Goodale. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009.

The Divided World: Human Rights and Its Violence by Randall Williams. Minneapolis, MN and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

After Evil: A Politics of Human Rights by Robert Meister. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2011.

The central tension of human rights is that they propagate a universal and singular human identity in a fragmented political world. No one writing about human rights ignores this tension, but the most important question we face in judging the value of human rights is how to understand this tension and the divisions it creates. The expected divisions between good and evil, between moral universalists and dangerous relativist, between dignified interventionists and cowardly apologists, have long given shape to human rights, as both an ideal and a political project. Seeing the problems of (and for) human rights in these habituated ways has dulled our capacity for critical judgment, as few want to defend evil or violent particularisms or advocate passivity in the face of suffering. Even among serious and determined critics our inherited divisions are problematic (and increasingly over rehearsed), whether we think of human rights as the imposition of Western cultural values, or in terms of capitalist ideology serving the interests of neo-liberal elites, or as an expression of exceptional sovereign power at the domestic and global levels. The ways that these divisions deal with the tension at the heart of human rights misses the ambiguity of those rights in significant ways.

Rather than trying to contain the tensions between singularity and pluralism, between commonality and difference, in a clear and definitive accounting, the authors of the texts reviewed here allow them to proliferate. Rather than trying to resolve the problem of human rights, they attempt to understand human rights in their indeterminate dissonance while exploring what they might become. To create and invoke the idea of humanity is not a political activity that is unique (either now or in the past) to the ‘West’. The people most dramatically injured by global capitalism sometimes fight their oppression by innovating and using the language and institutions of human rights. Political exceptions – the exclusion of outsiders, humanitarian wars and imperialist conceits – are certainly enabled by the same sovereign power that grants rights to its subjects, which is a metaphorical drama all too easily supported by human rights, but it is only a partial telling of the tale, a telling that leaves out how human rights can reshape political authority and enable struggles in unexpected ways. The work of these authors pushes us to reject the familiar divisions we use to understand the irresolvable tension at the centre of human rights and see the productive possibilities of that tension. If human rights will always be invoked in a politically divided world, and will also always create further divisions with each declaration and act that realises an ideal universalism, then our focus should be on who assumes (and who can assume) the authority to define humanity, the consequences for those subject to such power, and the ends toward which such authority is directed. Continue reading

The Royal Society has just released a fascinating report entitled “Neuroscience, Conflict and Security” that examines the increasing role that neuroscientific research is playing in the military today (thanks to Nick for drawing my attention to it). Indeed, as was reported by Wired’s Danger Room a couple of years ago, the US Air Force has been soliciting research proposals for “innovative science and technology projects to support advanced bioscience research” that include “bio-based methods and techniques to sustain and optimize airmen’s cognitive performance”, “identification of individuals who are resistant to the effects of various stressors and countermeasures on cognitive performance” and “methods to degrade enemy performance and artificially overwhelm enemy cognitive capabilities.” Likewise, DARPA (the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency that gave us the Internet) has long shown significant interest in the potential military applications of neuroscience.

As the Royal Society report puts it, military neuroscience can be seen to have “two main goals: performance enhancement, i.e. improving the efficiency of one’s own forces, and performance degradation, i.e. diminishing the performance of one’s enemy” (p.1). It is with reference to these two goals that I will attempt in this post to make some sense of the wider context and implications of neuroscience’s entanglement with contemporary martial practices.

This post summarises a piece for the European Journal of International Relations just published online. An inconsequentially different pre-publication version is also available for anyone unable to breach the pay wall.

UPDATE (8 March): Sage have kindly made the full EJIR paper open access until early April, so you can now get it directly that way too.

I’m sure you have reasons

A rational defence

Weapons and motives

Bloody fingerprints

But I can’t help thinking

It’s still all disease.

Fugazi, ‘Argument’ (2001)

‘Weapon of War’ could be many explanations and I’m not sure of any of them.

UNHCR official, Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo, June 2010

1. War Rape in the Feminist Imaginary

Rape is a weapon of war. Such is the refrain of practically all contemporary academic research, political advocacy and media reporting on wartime sexual violence. Once considered firmly outside the remit of foreign policy, rape is today labelled as a ‘tactic of war’ by US Secretaries of State who pledge to eradicate it and acknowledged as a war crime and constituent act of genocide at the highest levels of international law and global governance, a development which for some amounts to the ‘international criminalization of rape’. This idea of rape as a weapon of war has a distinctly feminist heritage. Opposed to the historical placement of gendered violence within the hidden realm of the private, feminist scholarship was the first to draw out the connections between sexual violence and the history of war, just as feminists fought to make rape in times of nominal peace a matter for public concern. Feminist academics have, then, pioneered a view of sexual violence as a form of social power characterised by the operations and dynamics of gender. Sexual violence under feminist inquiry is thus politicised, and forced into the public sphere.

But the consensus that rape is a weapon of war obscures important, and frequently unacknowledged, differences in our ways of understanding and explaining it. Continue reading

It took at least 200 years for the novel to emerge as an expressive form after the invention of the printing press.

So said Bob Stein in an interesting roundtable on the digital university from back in April 2010. His point being that the radical transformations in human knowledge and communication practices wrought by the internet remain in their infancy. Our learning curves may be steeper but we haven’t yet begun to grapple with what the collapsing of old forms of social space means. We tweak and vary the models that we’re used to, but are generally cloistered in the paradigms of print.

When it comes to the university, and to the journal system, this has a particular resonance. Academics find themselves in a strange and contradictory position. They are highly valued for their research outputs in the sense that this is what determines their reputation and secures their jobs (although this is increasingly the value of the faux-market and the half-assed quality metric). This academic authority, won by publications, is also, to some extent, what makes students want to work with them and what makes them attractive as experts for government, media and civil society. They are also highly valued in a straight-forward economic sense by private publishing houses, who generate profit from the ability to sell on the product of their labour (books and articles) at virtually no direct remuneration, either for the authors or for those peer reviewers who guarantee a work’s intellectual quality. And yet all (OK, most) also agree that virtually nobody reads this work and that peer review is hugely time-consuming, despite being very complicated in its effects. When conjoined with the mass noise of information overload and the extension and commercialisation of higher education over the last decades, our practices of research, dissemination and quality control begin to take on a ludicrous hue. As Clifford Lynch nicely puts it, “peer review is becoming a bottomless pit for human effort”.

This is an attempt to explore in more detail what the potentialities and limits are for academic journals in the age of digital reproduction. Once we bracket out the sedimented control of current publishers, and think of the liveliness of intellectual exchange encountered through blogs and other social media, a certain hope bubbles up. Why not see opportunity here? Perhaps the time is indeed ripe for the rebirth of the university press, as Martin Weller argues:

the almost wholesale shift to online journals has now seen a realignment with university skills and functions. We do run websites and universities are the places people look to for information (or better, they do it through syndicated repositories). The experience the higher education sector has built up through OER, software development and website maintenance, now aligns nicely with the skills we’ve always had of editing, reviewing, writing and managing journals. Universities are the ideal place now for journals to reside.

Tuesday 14th February 2012, 5.30pm-7.00pm

Westminster Forum, 5th Floor, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Westminster, 32-38 Wells Street, London W1 (nearest tube Oxford Circus)

Panel with Editors David Chandler and Meera Sabaratnam, followed by publisher’s reception

The 1990s was a weird decade for all kinds of reasons. The dice that were thrown into the air as the Soviet Union retreated landed in a particularly intriguing configuration for those politicians, public functionaries and academics from wealthy countries and institutions concerned with ‘peace’ and ‘development’. Their missions, marginalised for decades under concerns for national (i.e. military) security, were quite suddenly elevated as symbols of the new world order and installed as defining foreign policy priorities of wealthy states. Continue reading