A shorter version of this post appears at the Oxford University Press blog. It was invited – if that’s the right word – some months ago as a tie-in with the new edition of The Globalization of World Politics. Obviously, I was planning on writing about questions of imperial feminism and intersectionality. Things didn’t turn out that way. Apologies for repetition of good sense already promulgated elsewhere, and for the inevitable commentary fatigue.

If Hillary Rodham Clinton had triumphed in last Tuesday’s presidential election, it would have been a milestone for women’s political representation: a shattering of the hardest glass ceiling, as her supporters liked to say. Clinton’s defeat in the electoral college (but not the popular ballot, where she narrowly triumphed by about 640,000 votes at last count) is also the failure of a certain feminist stratagem: namely, the cultivation of a highly qualified, centrist, establishment (and comparatively hawkish) female candidate, measured in speech and reassuringly moderate in her politics. But the victory of Donald Trump tells us just as much about the global politics of gender, and how it is being remade.

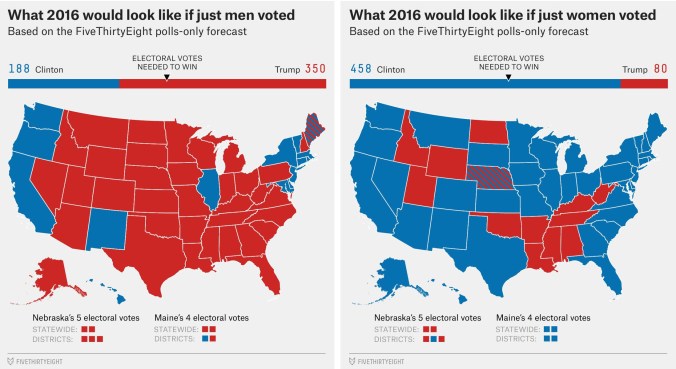

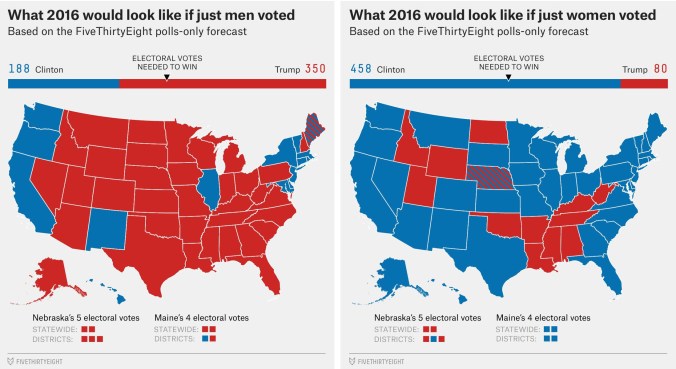

The election itself was predicted to be the most divided by sex in US history. Polls from a few weeks before the election had Clinton’s lead among women at the highest level for a presidential candidate since records began in 1952. A widely shared meme celebrated the trend and declared that “women’s suffrage is saving the world”. Activists from the ‘alt-right’ (a conglomerate of neo-Nazis, xenophobes, men’s rights types, lapsed libertarians and professional agitators) trolled in response that the 19th amendment should be repealed. Time called the election a ‘referendum on gender’; The New Yorker a question of ‘manifest misogyny’.

In the end, the politics of race mediated the politics of gender: white women were by many leagues more comfortable with Trump’s candidacy than women of colour. As Kimberlé Crenshaw pointed out on Wednesday morning, the claim for a singular female worldview – one that could be mobilised to ordain Clinton ‘Madame President’ – collapses under the pressure of other cross-cutting histories, interests, and ideologies (the idea that women share a common political perspective has of course been under attack within feminist theory for many decades). As has now been much rehearsed, NBC’s exit polls measured a 10% lead for Trump among white women, and an almost 20% lead amongst white women between the ages of 45 and 64. By contrast, CNN data indicated that 94% of black women voted for Clinton. Opinions now vary on how much blame to apportion suburban white women, or what have been called ‘Ivanka voters’, for the result. Somewhat confoundingly, Pew Research finds that the overall gender gap was indeed larger than in the last presidential elections (with women leaning Democrat). In either case the most significant shifts took place within the cohort of white voters (in favour of the Republicans).

And yet the power of race and racism in deciding the election should not be taken to mean that gender is irrelevant after all. As predicted, it was white men who voted for Trump in the greatest numbers. Trump is moreover symbolic of, and personally implicated in, a resurgent strain of misogynistic thinking: regularly dismissive of the intelligence and professionalism of women, speaking about them as sex objects or harridans, and fuelling conspiracy theories and denialism over sexual assault. And although the collapse in the predicted female vote for Clinton is surprising, it is at the same time no novelty to observe that women may also disqualify a politician on the basis of her sex – for example, in setting higher standards for female than male candidates, in believing that only men are aggressive enough for politics, or in judging women more harshly on their appearance and demeanour. Continue reading →

‘commitment to the men and women who live around you’, ‘recognizing the social contract that says you train up local young people before you take on cheap labour from overseas.’ And perhaps astonishingly, for a Conservative Prime Minister, May promised to deploy the full wherewithal of the state to revitalize that elusive social contract by protecting workers’ rights and cracking down on tax evasion to build ‘an economy that works for everyone’. Picture the Brexit debate as a 2X2 matrix with ideological positions mapped along an x-axis, and Remain/Leave options mapped along a y-axis to yield four possibilities: Right Leave (Brexit), Left Leave (Lexit), Right Remain (things are great) and Left Remain (things are grim, but the alternative is worse). Having been a quiet Right Remainer in the run-up to the referendum, May has now become the Brexit Prime Minister while posing, in parts of this speech, as a Lexiter (Lexiteer?).

‘commitment to the men and women who live around you’, ‘recognizing the social contract that says you train up local young people before you take on cheap labour from overseas.’ And perhaps astonishingly, for a Conservative Prime Minister, May promised to deploy the full wherewithal of the state to revitalize that elusive social contract by protecting workers’ rights and cracking down on tax evasion to build ‘an economy that works for everyone’. Picture the Brexit debate as a 2X2 matrix with ideological positions mapped along an x-axis, and Remain/Leave options mapped along a y-axis to yield four possibilities: Right Leave (Brexit), Left Leave (Lexit), Right Remain (things are great) and Left Remain (things are grim, but the alternative is worse). Having been a quiet Right Remainer in the run-up to the referendum, May has now become the Brexit Prime Minister while posing, in parts of this speech, as a Lexiter (Lexiteer?).