A guest post from Stephen Pampinella, continuing our occasional series on left/progressive foreign policy in the 21st century. Stephenis Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Relations at the State University of New York (SUNY) at New Paltz. His research interests include US state building interventions, hierarchy in international relations, race and postcolonialism, US grand strategy, and national security narratives. He is on leave from SUNY New Paltz during Spring 2019 and is conducting research on the practice of diplomacy in the Ecuadorian Foreign Ministry in Quito, Ecuador.

A guest post from Stephen Pampinella, continuing our occasional series on left/progressive foreign policy in the 21st century. Stephenis Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Relations at the State University of New York (SUNY) at New Paltz. His research interests include US state building interventions, hierarchy in international relations, race and postcolonialism, US grand strategy, and national security narratives. He is on leave from SUNY New Paltz during Spring 2019 and is conducting research on the practice of diplomacy in the Ecuadorian Foreign Ministry in Quito, Ecuador.

Alex Colás’ “The Internationalist Disposition” provides an excellent framework for evaluating foreign policy debates in the Democratic Party. The failures of the War on Terror combined with the emergence of economic and environmental threats have led many to engage in a far-reaching reappraisal of US foreign relations based on left critiques. This new approach toward foreign affairs is called progressive internationalism. It attempts to resolve the tension between adopting greater military restraint and remaining engaged in global governance.

But in recent weeks, establishment voices have sought to reassert their control over foreign policy debates by arguing for the necessity of US hegemony and classic liberal internationalist forms of cooperation. Colás’ methodological internationalism illustrates why traditional US foreign policy approaches will fail to provide actual security for ordinary Americans. It also suggests (somewhat counterintuitively) what kinds of grand strategies could do so. A great power concert strategy, in which the United States pursues a balance of power among its rivals while committing to more democratic forms of international cooperation, can best resolve the non-state threats to US democracy generated by its own liberal order.

The New Internationalism of the American Left

Colás describes methodological internationalism as a focus on macrostructural processes like capitalism or difference-based hierarchies which transcend state borders and generate worldwide categorical inequalities. We can contrast this perspective with methodological nationalism, the idea that the main units of analysis in world politics are nation-states. But rather than assume that international relations (IR) is about neatly bounded sovereigns pursuing their interests as autonomous actors, methodological internationalism privileges networks of social relations that constitute subjectivities in world politics. It refuses to accept that actors are constituted prior to their interactions with others and recognizes that the boundaries separating inside/outside are social constructs. What we see in domestic politics, including various struggles against economic exploitation and in defense of the environment and marginalized peoples, are really foreign policy problems that simply manifest themselves in a particular social context. This radical version of internationalism suggests that resolving our societies’ problems will require establishing democratic control over global processes on the basis of solidarity and respect for difference.

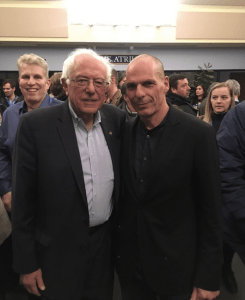

The emerging discussion around progressive internationalism builds upon this disposition. For example, Bernie Sanders and Yanis Varoufakis call for a global movement to revive democracy and oppose growing authoritarianism in the United States and Europe. Daniel Nexon argues that progressive multilateralists and anti-hegemony leftists can form a new foreign policy coalition that aims to lessen inequality through the deconcentration of economic power. Heather Hurlburt demonstrates that the United States can no longer pursue trade openness for the benefit of capital at the expense of workers as a means of extending its influence across the globe. All these ideas are consistent with methodological internationalism. Given the scale of transnational threats like inequalities produced by global capitalism and catastrophic climate change, a true progressive internationalism would prioritize intensive cooperation with other state and non-state actors to collectively regulate these global processes. The purpose of national security policy, then, would be to de-escalate great power competition as a means of enabling economic and ecological security.

Why Liberal Internationalism Will Fail (Again)

But in recent weeks, mainstream US foreign policy experts have provided their own spin in progressive internationalism. Advocates and practitioners of a traditional hegemonic foreign policy have sought to co-opt progressive internationalism in a series of essays which argue for the necessity of American power and global influence. These writers embody the post-Cold War centrist foreign policy coalition of liberal internationalists and neoconservatives. For them, that the greatest threat to the democratic “free” world created by the United States remains the autocratic governance model of Russia and China. While Washington should pursue cooperation on transnational governance issues where possible, they argue it cannot do so at the expense of making security concessions which would reward revisionist behavior by great power rivals. As in the past, American exceptionalism remains the identity narrative justifying a return to US hegemony, with Anglo-American norms serving as the basis for hegemonic socialization and cooperation.

The internationalist disposition is a reminder of why a mere social democratic twist on US hegemony will fail to provide actual security for the United States and its allies. Establishment voices continue to rely on state-centric assumptions about IR and ignore how state identities and interests are a function of their relationship with each other. Or, as Jennifer Mitzen and Michelle Murray might argue, the revisionist intentions of Russia and China are a product of their ontological insecurity. A hegemonic United States defending an Anglo-American order denies them recognition of their own great power identities and their right to participate in all deliberations about global order. From this perspective, we should challenge the implicit assumption made by Anthony Blinken and Robert Kagan that Russia is revisionist by nature. An internationalist perspective suggests that Russia has adopted those intentions in relation to a Wilsonian United States which seeks domination over Moscow and the transformation of its political system. The same is true for China, which rejects being cast as a “responsible stakeholder” by Washington which would eventually accept democracy following its internal transformation by global capitalism. In other words, the very terms of US relations with these states over the past 25 years is the source of their revisionist intentions, and not some essentialized feature of their domestic politics.

Further, a liberal exceptionalist narrative that contrasts “Eastern autocracy” with “Western freedom” masks how the United States has perpetuated its own systems of illiberal dominance throughout its history. Those same structures of oppression are the greatest threat to contemporary US democracy and also serve as glaring evidence of US hypocrisy. In his defense of American exceptionalism, Jake Sullivan represents institutional racism as a bug rather than a feature of the American political system by emphasizing the liberal ideals of the Founders and casting Donald Trump’s white ethnonationalism as an aberration. But this telling of the American story whitewashes the long history of an exclusive, white ethnic US identity dating back to the early 19th Century and its role in generating the modern United States. Scholars of American political development and US history have long demonstrated that institutions of slavery and land conquest constituted US society and made possible its economic prosperity rather than some kind of intrinsic tendency toward freedom.

Fast-forward to the present: liberal exceptionalism further denies how economic globalization made possible the rise of authoritarianism. Nils Gilman and David Klion rightly argue that the kleptocratic alliance between autocrats and oligarchs is the true threat to democracy and rule of law. Their ability to concentrate political and economic power has been enabled by the emergence of an integrated global market that privileges the freedom of capital over the needs of ordinary people, one created by the United States when liberal internationalism went global after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Finally, attempts to revive US hegemony will doom transnational efforts to deal with existential non-state threats. Hegemonists like Thomas Wright argue that Russia and China are the greatest threat to the United States, and that Washington should never make concessions to either power as a means of ensuring cooperation on issues of global governance. However, “ring-fencing” global capitalism and climate change as separate issues will fail to achieve the necessary level of cooperation to cope with these threats. National security policymakers cannot recognize that the greatest dangers faced by US citizens are non-state economic and ecological global processes that shape domestic politics from the inside-out, and not rival sovereigns. Economic destitution to the point of embracing fascist dictators coupled with environmental collapse are near-certain non-state threats which transcend our boundaries – in fact, as a global power, the United States has been complicit in creating them.

The internationalist disposition would suggest that the priorities of US foreign policy must change. Regulating global processes should be the primary objective, and it requires that the United States pursue intense macro-levels of cooperation with all other states, including its rivals, to achieve them. Yet it will be unlikely to do so if it remains wedded to liberal hegemony and consumed by great power competition. Short-term incentives to accumulate resources and power will override the long-term need for global governance. The result will be a world whose people live in precarity, ravaged by climate change, and constantly on the verge of great power war.

From “Disposition” to “Grand Strategy”

The internationalist disposition clearly illustrates why old US strategies are incompatible with the progressive internationalism of the US left. However, contra Colás, progressives should not avoid developing of a positive vision for foreign policy due to the diverse range of radical perspectives. To do so would cede pro-restraint arguments to structural realist and libertarian advocates of offshore balancing who offer no template for global engagement or institutional cooperation. What progressives must do is articulate a grand strategy, or a plan that mobilizes all elements of national power and influence, grounded in a relationalist ontology that combines restraint with internationalism. This strategy must be post-hegemonic (a term even Ikenberry has flirted with), post-statist, and supportive of intense international cooperation based on the diversity of identities and values otherwise ignored by the universalist pretenses of Anglo-American liberalism. If our very existence is mutually dependent on others, then we need a foreign policy based on solidarity in response to collectively experienced threats.

I think there is a strategy consistent with the international disposition: great power concert. A concert strategy requires that all great powers pursue mutual accommodation and recognize each other’s interests as part of a larger commitment to maintain international stability. Patrick Porter and Amitav Acharya argue that a great power concert strategy is the best suited to adapt to the transfer of wealth and power to Asia along with the “multiplex” nature of world politics (not to mention a global perspective on international relations). The emergence of a diverse range of state and non-state actors bound together by extreme interdependence makes it impossible for any one actor, such as the United States, to establish rules for global governance which can mobilize all others. On this basis, a concert strategy would lead the United States to collaborate with others on the basis of mutual co-existence and embrace joint decision-making at the global level for coping with macrostructural processes that threaten all peoples around the world. In this way, a concert strategy is firmly grounded the international disposition and can serve as the realization of progressive internationalism.

Security and The Balance of Power

A concert strategy can do what establishment foreign policy cannot, namely de-escalate great power competition by giving up US hegemony. If adopted, the United States would treat other great powers, like Russia, China, and Iran, as equal partners in the maintenance of global stability and incorporate their interests into regional security agreements. The United States would give up its self-assumed role as an unrivaled global hegemon and seek a balance of power based on mutual respect with other great powers as partners rather than enemies. This kind of international posture would result in a more horizontal great power system, one that Stacie Goddard as identified as being productive of status quo rather than revisionist intentions. It would be compatible with recognition of the great power identities of other states and provide them with ontological security.

Transitioning from a hegemonic security strategy to a balance of power one will require that the United States engage in some degree of retrenchment from its already expansive commitments. But supporters of hegemony are wrong when they claim that retrenchment will encourage great power aggression and lead to the abandonment of our allies. The United States can engage in moderate forms of retrenchment consistent with great power recognition while still maintaining commitments to allies that strive to uphold human dignity. For example, were the United States to support a moratorium on NATO expansion, as Michael O’Hanlon suggests, it would signal that the United States is no longer interested in moving the frontiers of its influence to the gates of Moscow and remove the sense of threat experienced by Russian leaders. By recognizing the validity of Russian security interests as well as its great power identity, the equal relationship made possible by a concert strategy will better deal with the threat of interstate conflict compared to US hegemony.

Reviving Global Governance

A concert strategy informed by the internationalist disposition can further enable more robust forms of global governance. Rather than attempt international cooperation based on a priori liberal normative templates, the United States would accept the validity of all claims made by collective actors in world politics in an open-ended and inclusive process of deliberation. The result would be less of a hegemonic order and more of a constitutionalist one, in which the United States binds itself to a truly democratic process of decision-making at the global level. The emergence of global governance norms would be a function less of hegemonic socialization and more of a right held by all actors to contest the validity of standards of expected behavior. In other words, a concert strategy would enable the United States to accept processes of norm contestation as the motor of transnational cooperation and generate more legitimate rules for regulating global governance. It would expand the US order building project initially identified by Ikenberry on the basis of restraint and institutional self-binding, but without retaining its own hierarchical position in world politics or engaging in hypocritical forms of dominance.

The implications for economic governance are profound: the United States would no longer exclude from consideration the notion of social democratic regulation of global capitalism and instead promote non-capitalist perspectives on the economy. Todd Tucker provides one great example of this approach when he argues that ISDS arbitration should include labor leaders and social justice advocates rather than international lawyers chosen by multinational firms which initiate legal action against sovereign states. It would also enable the United States to seriously consider Piketty’s call for a global wealth tax, Palley and Chow’s call for minimum wage floors, and a binding multilateral treaty that regulates global business activities on the basis of human rights. And finally, it would enable the drastic shift away from fossil fuels necessary to avoid climate apocalypse.

In Search of a Global Public

Naysayers might argue that all this degree of international cooperation sounds idealist, but all are possible in a context of declining great power competition. Once the United States recognizes the equal membership of all others in world politics on the basis of our extreme interdependencies, it can make possible what Mitzen has referred to as collective intentionality, or the emergence of a plural subject composed of several individuals who make and uphold joint commitments to each other and demand adherence as members of a global public. This kind of action is what the internationalist disposition can help us conceptualize, and even realize, through a concert strategy.

The Sanders Institute event for Progressives International. Source: Ada Colau, the mayor of Barcelona (in the picture).

If progressive internationalists want to realize their objectives, they should be willing to turn away from the US establishment and embrace a concert strategy. By prioritizing cooperation on non-state issues and resolving great power competition through equal recognition, they can realize security for their own citizens as well as others. However, IR constructivists remind us that no foreign policy can be enacted by policymakers without a legitimating national security narrative. Progressive internationalists must continue to develop a new story about the United States that rationalizes a concert strategy and renders US national identity compatible with the pluralism we find in both world politics and US domestic politics. To develop this narrative, progressive internationalists should engage radical critiques of democracy, like those offered by Chantal Mouffe, which seek maximal inclusion of others and accept difference and conflict as irreducible elements of political life. A pluralist strategic narrative can thereby serve as the basis for mutual respect of others and enable the democratization of world politics.

Pingback: Nightcap | Notes On Liberty

Pingback: Post up at The Disorder of Things – Stephen Pampinella

Pingback: Why Progressive Movements Must Engage Foreign Policy – Stephen Pampinella

I think, is more of a rising power than a great power at this point. But I understand the individuals who decided to use this term, it was mainly to signal to the US bureaucracy that the age of “Forever War”, as in counterterrorism, and the United States focusing on security threats that might not be so existential, is over.

LikeLike