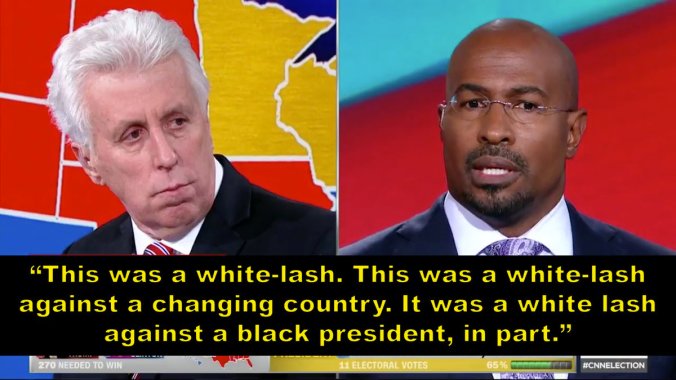

The election of a manifestly incompetent, billionaire bigot as president of the USA has come as a shock to many people, as indeed it should, and a vigorous debate has emerged over the causes. Many progressives, rightly horrified by the vile, nativist and sexist rhetoric of Trump’s campaign, seem to be concluding that it is this rhetoric that explains his success. Trump’s victory – enabled above all by white men – exposes the appeal of retrograde sentiment on gender – because voters rejected a highly-qualified woman for a self-declared ‘pussy-grabber’ – and race – since his supporters endorsed or at least disregarded his intensely racist rhetoric and policy pledges. Trump’s win thus expresses a ‘whitelash’ – a vile defence of threatened, white, male privilege. However, while sexists and racists undoubtedly supported Trump en masse, this thesis cannot explain how he was able to win. Indeed, it distracts attention from the most glaring cause of the outcome: the rot at the heart of America’s democratic system in general and of the Democratic Party in particular.

In brief, the ‘whitelash’ thesis is that white, middle-class and especially male voters reacted against Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, drawn to Trump’s clearly racialized promises to ‘take their country back’. The thesis draws on facts like the following. 67% of white men backed Trump. His supporters prioritised the (racialized) issues of immigration and terrorism over the economy. Confounding some talk of an anti-neoliberal revolt, Trump voters were not the poorest, earning under $50,000 per year (these folks voted mostly for Clinton); they are middle-income workers (the so-called ‘middle class’), who care more about affirmative action allowing minorities to steal jobs from whites than they care about trade offshoring jobs. So they voted for Trump not out of real economic plight, but because they feel their white privilege slipping away to non-whites and, for men, to women also. They felt that ‘eight years of one demographically symbolic president [was] enough’, blaming their economic grievances on a black president instead of Ronald Reagan, whose policies actually started the rot. And they voted ‘against an economy they believed was giving women a step up’. The most subtle versions of the thesis admit that not all voters may have been motivated by such concerns, but they nonetheless ‘gave force’ to these retrograde views by endorsing Trump.

No doubt this portrait describes a certain hard-core minority of American voters. Even some defenders of the ‘white working class’ admit they can express some pretty retrograde attitudes. Nonetheless, there is no way that this thesis can account for Trump’s victory.

The simple reason is that there was no surge for Trump, even among the white working class; on the contrary, support for the Republicans fell – it just fell much more for the Democrats. In fact, the hallmark of the 2016 presidential election is the radical disengagement of vast numbers of citizens from the democratic process.

This is obvious merely from turnout data, which is being scrupulously analysed on Facebook by Kole Kilibarda. As he puts it: in 2012, the two major parties got about 125m of 130m votes cast, while 90m eligible voters did not vote; in 2016, they got 122.5m of 130m votes cast, while 100m eligible voters (higher due to population growth) abstained.

Data compiled from electproject.org

White voters did not support Trump significantly more than Mitt Romney in 2012: there was only a 1% swing, to 58% for Trump/37% for Clinton. That is, disproportionate white support for Republican presidential candidates is a longstanding fact (going back to Lyndon Johnson’s repudiation of the ‘Dixiecrats’), and did not substantially change in 2016. Evidence from the five ‘rust belt’ states that fell unexpectedly to Trump shows that he only picked up about 300,000 white working class votes. This makes it hard to sustain the idea of a whitelash against Obama.

Indeed, overall, Trump not only got fewer votes than Clinton but also about 400,000 fewer than Romney. He was not a popular candidate whose ideas and rhetoric enthused most Americans. He won just 47.2% of the vote, or 21.6% of the eligible electorate. Many who did vote for Trump did not like him: 57% of whites thought him untrustworthy; a quarter said he was unqualified and lacked the right temperament; and only 42% of his supporters ‘strongly favoured’ him, while 61% of citizens had an unfavourable view of Trump. Many Trump voters also disagreed with key policy positions like deporting illegal immigrants. Trump did not boost his vote with his ‘whitelash’ trash-talk – he didn’t even hold up the Republican vote from 2012. At best, he managed to rally the traditional Republican base – and little more than that.

So the question is not so much why Trump won, but why Clinton lost to such a poor opponent. The fact is that while the Republican vote declined, the Democrat vote collapsed. It fell from 69.5m in 2008 and 65.9m in 2012 to just 61.3m, despite the electorate increasing by over 18m over this period. Turnout was especially bad in states that Clinton lost. Kilibarda’s analysis of the Rustbelt-5 shows that while Trump picked up 300,000 working-class votes, Clinton lost 1.5m as voters either went for third-parties (about 500,000) or abstained. As Kilibarda puts it: ‘Trump did not “flip” these states as much as the Democrats lost them.’ Problematically for the whitelash thesis, Clinton’s collapse was worst among minority voters: compared to Obama in 2012, she was down 8 points among African-Americans and Latinos, and 11 down among Asians. Accordingly, 8% of blacks, 29% of Latinos, 29% of Asians and 37% of ‘other’ minorities voted Republican. This was particularly devastating because demographic change was supposed to work against Trump, with the white share of the electorate declining from 72% to 70% from 2012-16.

So the truth is that white and minority voters abandoned the Democrats en masse; but white voters did not rush for Trump. Far from being the gullible fools of much liberal commentary, somehow believing that the oligarchic Trump was their saviour, they refused to vote for either party, backing third candidates or simply abstaining. Indeed, the 100m citizens who did not vote are the crucial force in this election, dwarfing the voters supporting either main party. Put simply, Trump could not even maintain Republican support levels from 2012, winning thanks only to 107,000 votes in just swing three states. If Clinton had been able to mobilise just 1% of the non-voting population where it mattered, Trump would have lost.

Her failure to do so cannot be understood independently of racism or sexism. It is true that local laws requiring voters to show photo ID tend to affect (or indeed target) minorities more than whites, which one study suggests depresses Democrat votes more than Republican ones. We will not know their true effect until turnout data is clearer. It is also true that Clinton was down 5 points with men, including Democratic men, while gaining only 1% among women on 2012, and her big collapse among black voters was with men, not women – providing stronger support for a sexism thesis than a racism one, particularly when we consider how many voters had backed Obama in 2008 and 2012. However, race also intersects here: as one commentator puts it, if white working class women had split 50/50 instead of 62/34 for Trump, Clinton would have won.

Nonetheless, invoking these factors as a primary explanation implicitly assumes that Clinton’s platform was good, especially relative to Trump’s, and so a lack of support can only be attributed to malign forces and motives. But actually, many people did not feel her platform was good. No more voters felt enthused by a Clinton presidency than a Trump one – just 4 in 10 for each. 44% of eligible voters viewed her unfavourably. Obama at least offered ‘hope’ and ‘change’, with big ideas on healthcare and the like – though his failure to deliver much arguably explains his waning support in 2012. But Clinton was a pale imitation. She is the quintessential establishment candidate; her sole claim to ‘change’ was to be America’s first woman president.

This may have put off some male voters, as stated above – but it clearly failed to enthuse women, too, given their tiny 1% swing towards Clinton. Some commentators have been quick to blame ‘internalised misogyny’ or female ‘sexism’, especially among whites. But perhaps – just perhaps! – women wanted a bit more and so refused, in Susan Sarandon’s words, to ‘vote with their vaginas’. They stand condemned because they refused to obey the diktat of neoliberal identity politics, preferring instead to vote on other issues.

The same goes for the so-called ‘middle class’ – not the poorest citizens, who are kept afloat by Democrat policies and vote accordingly, but middling workers who, despite working hard, are experiencing declining living standards and feel pessimistic about the future (a parallel here to Brexit). Certainly, some of their grievances may take a racialized form as they blame immigrants or minorities. But what alternative form did Clinton suggest that it take? Unlike Bernie Sanders, who promoted an explicitly class-based framework, it is impossible to say what Clinton offered these people, because she barely addressed their concerns. Clinton has been a leading figure in an increasingly technocratic political class that, since the 1980s, has largely ignored working people, abandoning them to the mercies of the free market, neoliberal trade deals, and stagnating real wages, while cosying up to Wall Street and billionaire donors. ‘Middle-class’ voters would be foolish to believe that Trump would do much differently, but nor can they reasonably have much faith that Clinton will depart from form. Her elitist disdain for Trump’s ‘basket of deplorables’ simply compounded her enormous distance from ordinary voters.

The 2016 US presidential election, then, is a sad story of the hollowing out of America’s representative democracy. The rot was halted temporarily by Obama’s promise of hope and change, but resumed quickly enough. The so-called ‘Grand Old Party’ could not generate a single serious candidate to rival a perma-tanned reality TV star, and even this wild populist could not maintain – let alone increase – Republican support. And the best the Democrat establishment could field was someone loathed by much of the electorate. A hundred million Americans felt so divorced from the political process, so unrepresented by either political party, that they could not bring themselves to vote for anyone. The result is a president that only a small minority of American voters actually wanted.

Of course, it may still be objected that it is all very well for white workers to abstain; thanks to their ‘white privilege’ they won’t bear the brunt of Trump’s nasty policies. While those pushing this line still struggle to explain (i.e. conveniently ignore) the millions of non-white voters supporting Trump, the more important response is this: in a democracy, a settlement that serves the interests of minorities cannot be created without simultaneously appealing to the interests of the majority. For this reason, fragmented identity politics won’t do. An inclusive socialist platform, capable of appealing to workers of all sexes and ethnicities, remains essential.

This post is a lightly edited version of one at The Current Moment.

Pingback: Charlottesville and the Politics of Left Hysteria | thecurrentmoment

Pingback: Episode 27: “Stay in Your Lane!” — Special Commentary Episode on the 2020 US Election, and the Puzzling Prevalence of the K-Hive in American Academia | #OCCUPYIRTHEORY