The Disorder of Things is delighted to welcome a post from John M. Hobson, which kicks off a blog symposium on his new book The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics: Western International Theory, 1760-2010. Over the next few weeks there will be a series of replies from TDOT’s Meera and Srdjan, as well as special guest participant Brett Bowden, followed finally by a response from John himself. [Images by Meera]

The Disorder of Things is delighted to welcome a post from John M. Hobson, which kicks off a blog symposium on his new book The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics: Western International Theory, 1760-2010. Over the next few weeks there will be a series of replies from TDOT’s Meera and Srdjan, as well as special guest participant Brett Bowden, followed finally by a response from John himself. [Images by Meera]

Update: Meera’s response, Srjdan’s response and Brett’s response are now up.

Introduction

As I explain in the introduction to The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics, my book produces a twin-revisionist narrative of Eurocentrism and international theory.[i] The first narrative sets out to rethink the concept of Eurocentrism – or what Edward Said famously called ‘Orientalism’ – not so much to critique this founding concept of postcolonial studies but rather to extend its reach into conceptual areas that it has hitherto failed to shed light upon.[ii] My central sympathetic-critique of Said’s conception is that it is reductive, failing to perceive the anti-imperialist face of Eurocentrism on the one hand while failing to differentiate Eurocentric institutionalism or cultural Eurocentrism from scientific racism on the other hand. As such, this narrative is one that is relevant to the many scholars who are located throughout the social sciences and who are interested in exploring the discursive terrain of ‘Eurocentrism’. These, then, would include those who are located in International Relations of course but also those in Politics/Political theory, Political Economy/IPE, political geography, sociology, literary studies, and last but not least, anthropology.

The second narrative rethinks international theory as it has developed across a range of disciplines. It stems back to the work of Adam Smith in the 1760s and then moves forwards down to 1945 through the liberals such as Kant, Cobden/Bright, Marx, Angell and J.A. Hobson, Zimmern, Murray and Wilson, onto the Marxists such as Marx and Engels, Lenin, Bukharin, and Luxemburg, and culminating with the realists who include Mahan and Mackinder, Giddings and Powers, Ratzel, Kjellén ,Spykman, von Bernhardi, von Treitschke and, not least, Hitler. After 1945 I include chapters on neo-Marxism (specifically neo-Gramscianism and world-systems theory), neo-liberalism (the English School and neoliberal institutionalism) and realism (classical-realism, hegemonic stability theory and Waltzian neorealism). This takes the story upto 1989. I then have two chapters on the post-Cold War era which examine what I call ‘Western-realism’ and ‘Western-liberalism’. The final chapter provides an overview of the changing discursive architecture of Eurocentrism and scientific racism, while also revealing how international theory has, in various ways, always conceived of the international system as hierarchic rather than anarchic. Although this is clearly a highly controversial and certainly counter-intuitive claim, it nonetheless in effect constitutes the litmus test for the main claim of the book: that international theory for the most part rests on various ‘Eurocentric/racist’ metanarratives. And ultimately my grand claim posits that international theory in the last quarter millennium has not so much explained international politics in an objective, positivist and universalist manner but has sought, rather, to parochially celebrate and defend or promote the West as the pro-active subject of, and as the highest or ideal normative referent in, world politics.

However, while many non-IR specialists might well have an interest in thinking more deeply about Eurocentrism, equally though, they might well be put off from reading a book that appears to be aimed at an IR audience. But I want to emphasize that I treat IR theory in two ways in this book. First, I treat it as the subject of interest in order to reveal how the majority of it is embedded in various Eurocentric metanarratives. This is a story that naturally would have principal interest for an IR audience though political economists, sociologists and political geographers will find numerous thinkers who reside within their disciplinary fields. But I also focus on international theory as the object of analysis by treating it as a vehicle, or repository, of the various Eurocentric metanarratives. Given the point that for Edward Said, Orientalism/Eurocentrism has a clear normative link with international politics – specifically imperialism – then it surely makes sense to focus on international theory as a potential reflector of such metanarratives. Put differently, if one cannot find evidence or traces of this discourse within international theory then this would surely knock a major dent in the postcolonial assumption that social science theory is largely Eurocentric.

Thus the first narrative of the book explores the multiple forms that Eurocentrism has taken and how its discursive architecture changes over time. A decade ago perhaps, this focus would be one that would be of interest only to non-IR readers. But particularly in the last decade postcolonial analysis has reached a critical take-off threshold within the discipline of IR, albeit mainly outside of the United States. I mention this because the three people who have very kindly and indeed enthusiastically agreed to take part in this blog forum are all IR scholars who have a strong interest in Eurocentrism and how it infects IR theory. It is also the case that they have all produced some very fine scholarship on postcolonial IR, with Brett Bowden’s excellent book, The Empire of Civilization, comprising one of several books that part-inspired the research for my own book.[iii] I am also extremely impressed by Srdjan Vucetic’s superb book, The Anglosphere, as I have been by the work of Meera Sabaratnam.[iv] I would also like to point out that there is another important link between my own book and that of Bowden’s which I would like to mention. For I was privileged to be the external examiner of Bowden’s ANU PhD thesis, ‘Expanding the Empire of Civilization: Uniform, nor Universal’, which was later expanded into his 2009 book. While I was delighted to award it a straight pass, I did suggest in my examiner’s report that he should convert this into a book, which happily transpired several years later (though I shall refrain from taking the credit for that!) and that were he to do this he might want to consider my claim that Said’s conception is problematic in various respects and that it needs further consideration and deeper exploration. Without realizing it at the time, I can now see that some of the key suggestions which I made in my 2004 report turned out to comprise the building blocks of my own book that eventually came out in 2012.

In part, then, because of the particular theoretical predisposition of these three writers, I choose to focus in this brief introduction on issues that speak to those who are interested specifically in engaging my revisionist understanding of Eurocentrism. As such, this speaks to the first thematic narrative of my book which I think is of interest to people outside of IR as well as to those inside it who are of a postcolonial bent. Certainly this is not to deny that a forum which comprises Marxists, liberals and realists would be particularly interesting given that I have focused on them as vehicles of various Eurocentric and/or racist metanarratives. But that is, hopefully, for another time. Here I am keen to take this opportunity to engage postcolonial inspired thinkers in order to gauge their reactions to my revisionist conceptual moves that I make vis-à-vis Eurocentrism. And, of course, since none of these writers would find it controversial to claim that most of IR theory is Eurocentric, then such a conceptual focus on Eurocentrism makes all the more sense. Still, this is by no means to ‘outlaw’ any discussion of IR theory should my interlocutors be so inclined; merely to flag up to a potential readership the kinds of issues that I think are most relevant here.

Revisioning the Postcolonial Conception of Eurocentrism/Orientalism: Points of Potential Controversy

There are several areas that I assume might provoke controversy with postcolonial thinkers, two of which I shall take in turn. I do not know if my respondents will find these points controversial. But I feel that they are worth airing if only to give a potential readership a flavour of the book.

I. Splitting Finitudes or Splitting Hairs?

The first move I make in re-visioning Eurocentrism/Orientalism is to overcome what I see as Said’s tendency towards reductionism. I see this reductive tendency as playing out in two ways. First, while Said conceptualised Orientalism/Eurocentrism as a monolithic construct my own reading of a large range of texts suggests very clearly that there are two generic constituent categories of what Said calls ‘Orientalism’. These are ‘Eurocentric institutionalism’ (EI from henceforth) or what might be called ‘Cultural Eurocentrism’ on the one hand and ‘scientific racism’ (SR from henceforth) on the other. In essence, EI focuses on culture and institutions as the location of difference. In this imaginary, the West has been constructed as superior on the grounds that its culture is founded on high and exceptional degrees of rationality. Conversely the East is constructed as inferior on the grounds that its culture and institutions are based on high degrees of irrationality. It is this that gives rise to the familiar series of logocentric binaries which supposedly depict the difference between the West (the privileged first term) and the East (the derogatory second term): democracy/Oriental despotism or robust state/state of nature, individualism/collectivism, capitalism/feudalism or nomadism, sane/insane, science/superstition or magic etc. Equally, these logocentric binaries are also generated in the scientific racist imaginations. The difference is that the generator of this racist grammar rests primarily on genetic difference (whether this is something that is inherent to particular races or is something which is shaped by the nature of the physical environment/climate or even the nature of social practices in combination with a particular environment/climate).

The second move I make is to break the Gordian Knot that Said believes links Orientalism to imperialism. Here I argue that both SR and EI can be either anti-imperialist or imperialist. Naturally this is a potentially heretical move and I will be particularly interested in what my postcolonial interlocutors make of this assertion. Either way, the basic conceptual heuristic is laid out below in table 1.

Table 1: The four basic variants of generic Eurocentrism in international theory

| Pro-imperialist | Anti-imperialist | |

| Eurocentric Institutionalism | (A) Paternalist | (B) Anti-Paternalist |

| Scientific Racism | (C) Offensive | (D) Defensive |

At this point it is also worth noting the key differences between my ‘non-reductive’ conception and that of Said’s, which are laid out in Table 2.

Table 2: Alternative conceptions of Orientalism/Eurocentrism

| Said’s reductive conception of Orientalism | ‘Non-reductive’ conception of Eurocentric Institutionalism & Scientific Racism | |

| Relationship of Orientalism and Scientific Racism | Inherent Racism, especially social Darwinism and Eugenics, is the highest expression of imperialist-Orientalism | Contingent Racism and Eurocentric institutionalism are analytically differentiated even if they share various overlaps |

| The centrality of the ‘standard of civilization’ | Yes | Yes |

| Agency is the monopoly of the West | Inherent The West has hyper-agency,the East has none | Contingent The West always has pioneering agency, while the East ranges from high to low levels of agency; but where these are high they are deemed to be regressive or barbaric |

| Propensity for imperialism | Inherent | Contingent Can be imperialist and anti-imperialist |

| Sensibility: Propensity for Western Triumphalism | Inherent | Contingent Racism is often highly defensive and reflects Western anxiety. Some racist thought and much of Eurocentric institutionalism exhibits Western self-confidence, if not triumphalism |

This table adds in two other features that differentiate my conception from Said’s. First, that far from presenting a picture of Western hyper-agency and Eastern passivity/inertia I find that many thinkers – especially some of those of a scientific racist bent – award various Eastern races high if not very high levels of agency. The likes of arch-Eugenicist Lothrop Stoddard, for example, paints the Muslims and the East Asians with extremely high levels of agency. True, much of this is viewed in highly pejorative terms insofar as Stoddard paints these races with high levels of ‘predatory’ agency such that they constitute a massive threat to white racial supremacy. But Stoddard also argues that these races – especially the Muslims – have high levels of ‘constructive’ agency, insofar as they are able to forge their own path to modernity over and above simply copying the path that the Europeans took. Such a posture vis-à-vis ‘constructive agency’ treads quite close to the kind of approach that postcolonialists embrace. And then there are the liberal anti-imperialist Eurocentric institutionalists such as Adam Smith and Immanuel Kant, who believe that non-European societies will spontaneously develop or auto-generate into modernity (even if in the process they will simply follow the path that was pioneered or trailblazed by the Europeans). Both these examples suggest that the two most common posited postcolonial antidotes to Eurocentrism/racism – the importation of Eastern agency on the one hand and the critique of imperialism on the other – are not as self-evidently true, or indeed as obvious, as we have been led to believe.

The final definitional point of differentiation concerns the ‘temperament’ or ‘sensibility’ of EI and SR. It is commonly believed that Eurocentrism embodies a highly triumphalist sense of Western superiority, of which SR in general and Eugenics in particular allegedly represent its most extreme expression. But I find that many scientific racists, especially many Eugenicists, were wracked with insecurity, paranoia and fear, and stood trembling in the face of an all-powerful barbaric foe. In fact, what I find perplexing is not so much this position but that it should be at all surprising to find a strong association between scientific racism and a paranoid fear of the other. Recall that the Ku Klux Klan formed in response to the legal privileges that the Negroes received in the guise of the 13th and 14th Amendments to the US constitution. Recall too that Adolf Hitler was terrified that Aryan supremacy was being eroded by the dysgenic impact of inter-racial mixture with Jewish blood, not to mention the point that the Jews seemed to be taking over the world. This is not to downplay the sense of supreme white confidence that many scientific racists held (such as Theodore Roosevelt or Winwood Reade). But it is to say that paranoia and fear of the other are important components of the scientific racist oeuvre.

At this point I wonder if and to what extent my postcolonial interlocutors will find all this persuasive or whether in breaking the Gordian Knot between EI/SR and imperialism I am merely splitting conceptual hairs at the cost of throwing the postcolonial baby out with the bathwater. For cutting this link necessarily takes the postcolonial critique into new and unexplored territory which, if nothing else, might fill my postcolonial interlocutors with a sense of trepidation. Either way, though, my sense is that postcolonialists often feel that they need to identify an imperialist political cue in a particular thinker’s writings in order to be able to reveal an underlying Eurocentrism. But bringing in an anti-imperialist face to EI and SR means that this avenue is partially blocked off. In sum, then, I ask my interlocutors whether in dividing ‘Orientalism’ into four generic components I am succeeding in splitting Said’s conceptual monolith into useful and illuminating finites, though at times overlapping, categories or whether I am simply splitting conceptual hairs in a theoretically dangerous manner.

II. From Splitting Finitudes To An Historical Sociology Of Discursive Change

If my exercise in the previous section is deemed to be problematic and that I would have been better off by sticking to Said’s monolithic conception of Eurocentrism, then this means that a second key goal of the book also becomes redundant. Thus suggesting that there are a number of variants means that it becomes possible to reveal the changing discursive architecture of ‘generic Eurocentrism’ in the last 250 years. Put differently, Said’s conception is limited in its ability to reveal discursive changes over time. How then has generic Eurocentrism changed or morphed over time?

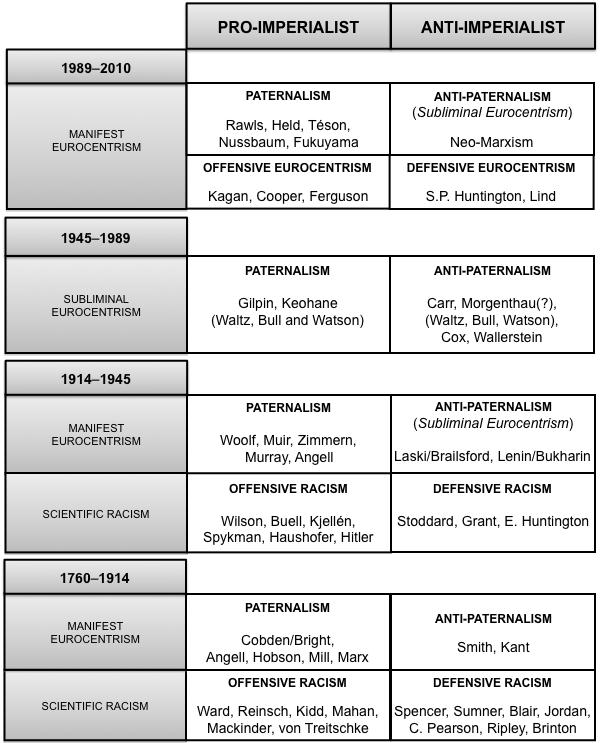

I identify a number of eras. Put at its bluntest, the 1760 through 1945 era was dominated by what I call manifest EI/SR, while from 1945–1989 subliminal Eurocentric institutionalism was dominant, with the spectre of SR pretty much exorcised from the international body theoretique. And then after 1989 manifest EI returns to dominate mainstream international theory while subliminal Eurocentrism for the most part retreats into large parts of critical theory. Thus after 1989 what I call ‘Western-realism’ goes back to the future of post-1889 imperialist racist-realism, while post-1989 ‘Western-liberalism’ returns us back to post-1830 paternalist-Eurocentrism. I differentiate ‘subliminal’ from ‘manifest’ Eurocentrism on the basis that the former reproduces many of the aspects of the latter but that its Eurocentric properties are far more hidden from view.[v] Thus in its subliminal form all explicit talk of imperialism is dropped, with imperialism often going by a term that dares not speak its name – as in, for example, neorealist discussions of American or British hegemony (see chapter 8). Equally, explicit talk of ‘civilization versus barbarism’ is largely dropped in favour of its equivalent ‘sanitised’ terms: ‘modernity versus tradition’ and ‘core versus periphery’. This discourse underpins classical realism and neorealism (discussed in Chapter 8), neoliberal institutionalism and classical pluralist English School theory (discussed in Chapter 9), as well as much of neo-Marxism (discussed in Chapter 10) and large parts of classical Marxism (discussed in Chapter 6). The changing discourse of EI/SR in the quarter millennium, 1760–2010, is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3: Mapping the changing architecture of ‘Eurocentrism/Scientific Racism’ in international theory in the four key eras, 1760–2010

Notes:

1. All references to Eurocentrism are to ‘Eurocentric institutionalism’.

2. I have not included all the thinkers I consider in this book so as not to clutter the figure.

3. Those who fit in more than one box have been placed in brackets.

At this point I shall close my introduction rather than raise more issues, for it would be nothing if not imperialist were I to dictate the terrain upon which my interlocutors should be confined to. For it might well be the case that there are a series of issues that they want to bring to the table that I have not touched upon. And, if nothing else, this brief introduction at least serves to give a potential reader a flavour of the book.

[i] J.M. Hobson, The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics: Western International Theory, 1760–2010 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

[ii] Edward W. Said, Orientalism (London: Penguin, 1928/2003).

[iii] Brett Bowden, The Empire of Civilization: The Evolution of an Imperial Idea (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2009).

[iv] Srdjan Vucetic, The Anglosphere: A Genealogy of a Racialized Identity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011); Meera Sabaratnam, ‘IR in Dialogue… but Can We Change the Subjects? A Typology of Decolonising Strategies for the Study of World Politics’, Millennium 39(3) (2011): 781–803.

[v] Note that this distinction should not be confused with Said’s contrast between what he calls ‘manifest’ and ‘latent’ Orientalism (Said 1978/2003: ch. 3).

Pingback: Paletleme Amirliği, 19 Eylül 2012 « Emrah Göker'in İstifhanesi

Pingback: Political theory | Pearltrees

What mainstream international theory, in its distortion of international politics, leaves out in its analysis is no coincidence. Indeed, it has a “wilful amnesia” (Krishna 2001). This leads onto to the next reason as to why the Anglo-American monopoly over the production of international theory matters: its euro-centrism and distortion of international politics significantly contributes to a covert legitimisation of imperialism (Barnett 2002). Here, what is being highlighted is that its contextual production is significant due to the relationship between power and knowledge (Jones 2004).

LikeLike

In response to “Gold Price”, I do agree that Eurocentrism can legitimise imperialism. But I think that where postcolonialism can go wrong is assuming that all Eurocentric theory is necessarily imperialist. Much of neo-Marxism, in my view, is Eurocentric but 99.9 per cent of it argues vehemently against imperialism. Even scientific racism has its anti-imperialist voices, despite the popular assumption that scientific racism was simply the most vitriolic discourse, or the highest discursive form, of imperialism. I do believe that this thing that goes by the generic label of Eurocentrism or Orientalism is a vastly complex being that defies reductive treatment. But the proof of the pudding, I guess, lies in whether the book can persuade Gold Price and others of this claim…

LikeLike

Pingback: Defining Theory Down » Duck of Minerva