This post summarises a piece for the European Journal of International Relations just published online. An inconsequentially different pre-publication version is also available for anyone unable to breach the pay wall.

UPDATE (8 March): Sage have kindly made the full EJIR paper open access until early April, so you can now get it directly that way too.

I’m sure you have reasons

A rational defence

Weapons and motives

Bloody fingerprints

But I can’t help thinking

It’s still all disease.

Fugazi, ‘Argument’ (2001)

‘Weapon of War’ could be many explanations and I’m not sure of any of them.

UNHCR official, Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo, June 2010

1. War Rape in the Feminist Imaginary

Rape is a weapon of war. Such is the refrain of practically all contemporary academic research, political advocacy and media reporting on wartime sexual violence. Once considered firmly outside the remit of foreign policy, rape is today labelled as a ‘tactic of war’ by US Secretaries of State who pledge to eradicate it and acknowledged as a war crime and constituent act of genocide at the highest levels of international law and global governance, a development which for some amounts to the ‘international criminalization of rape’. This idea of rape as a weapon of war has a distinctly feminist heritage. Opposed to the historical placement of gendered violence within the hidden realm of the private, feminist scholarship was the first to draw out the connections between sexual violence and the history of war, just as feminists fought to make rape in times of nominal peace a matter for public concern. Feminist academics have, then, pioneered a view of sexual violence as a form of social power characterised by the operations and dynamics of gender. Sexual violence under feminist inquiry is thus politicised, and forced into the public sphere.

But the consensus that rape is a weapon of war obscures important, and frequently unacknowledged, differences in our ways of understanding and explaining it. Like  most work in academic feminism, politicised inquiry into wartime sexual violence has often shown an awareness of differences within feminism. Most prominently, Inger Skjelsbæk has argued that feminist accounts can be divided into three epistemologies depending on who they conceptualise as the victims of wartime sexual violence: essentialists (who see all women as victims through a focus on the militarised expression of underlying masculinity); structuralists (who see only some women as under threat and work from a group-based perspective); and social constructionists (who allow that both men and women may be victims and understand femininity and masculinity as malleable categories that could conceivably be applied to anyone within conflict contexts). Others have, for example, differentiated approaches to the Bosnian mass rapes, either identifying sexual violence as specifically genocidal or seeing it as of a piece with ‘everyday’ rape in war.

most work in academic feminism, politicised inquiry into wartime sexual violence has often shown an awareness of differences within feminism. Most prominently, Inger Skjelsbæk has argued that feminist accounts can be divided into three epistemologies depending on who they conceptualise as the victims of wartime sexual violence: essentialists (who see all women as victims through a focus on the militarised expression of underlying masculinity); structuralists (who see only some women as under threat and work from a group-based perspective); and social constructionists (who allow that both men and women may be victims and understand femininity and masculinity as malleable categories that could conceivably be applied to anyone within conflict contexts). Others have, for example, differentiated approaches to the Bosnian mass rapes, either identifying sexual violence as specifically genocidal or seeing it as of a piece with ‘everyday’ rape in war.

Although useful, some of these distinctions risk repeating the ‘familiar stories’ that Clare Hemmings warns of, parcelling kinds of feminism into chronological chambers (first there were the essentialists…). Most crucially, it has not been obvious at which level the conflict between conflicting theoretical accounts lies. For example, the apparent dispute between an account of wartime sexual violence in which all women are targeted and one in which men and women are targeted may tell us much more about contingent historical factors (different wars and differing contexts may display different patterns of rape) or analytical distinctions (between acts that are essential to a strategy and those that are peripheral to it) than they do about the philosophical foundations of research. Despite a general concern with multiple feminisms, then, in the case of wartime sexual violence it has generally seemed more important to distinguish feminist from non-feminist analysis and to make the case for war rape as a legitimate topic for the attention of IR scholars than to open up varieties of feminist analyses to scrutiny.

Why not think of feminist accounts of war rape differently? Given the multiple ways in which ‘explanation’ has recently been opened up as a category, could we not think of feminism as embodying different kinds of substantive analysis, different logics of sexual violence expressed in different packages (or assemblages) of scholarly discourse? Following interventions opening these possibilities, we can see different feminist accounts of sexual violence as falling within separate modes of critical explanation, united by common themes and assumptions, differentiated from other modes by the distinctive way in which they assemble and cohere accounts of the social world.[1]

Modes are not mere collections of formal hypotheses, but instead combine different forms of intellectual practice. In this framework, that is taken to mean that they combine analytical wagers (organising concepts which ‘select’ objects of inquiry and underlying explanatory categories like ‘rationality’ or ‘affect’); narrative scripts (the stories we tell about objects of inquiry and the ways in which we people and script our accounts with particular kinds of protagonists acting for particular reasons); and normative orientations (the ideas of responsibility, blame and possible political action implicated in the wagers and scripts that characterise a particular mode) (I’m summarising some dense stuff pretty quickly here, but there’s more detail in the full paper, I promise).

2. The Cunning of Reasons: Instrumentality, Unreason, and Mythology

Turning to a substantive analysis of different explanations of war rape, three explanatory modes are revealed. Existing accounts of rape as a weapon of war have privileged instrumentality, unreason or mythology as modes of wartime sexual violence. Each mode carries its own analytical style in its elements, articulated through a focus on particular empirical regularities and a corresponding characterisation of instances of sexual violence. All have a plausibility when dealing with particular examples. However, the shifting nature of both the modes and of the phenomena under analysis resists any easy preference for one mode over others or reduction of them to three separate and wholly incommensurate hypotheses of sexual violence. The modes are coherent but not in the sense of being directly competing paradigms. They are partly overlapping, and ambiguous at the margins, but also apparently contradictory on a range of key analytical problems.

Instrumentality signifies self-conscious means-ends reasoning at its purest. Put directly, rape is cheaper than bullets. It recalls, within a gendered register, the ‘Machiavelli Theorem’ of one economist – that “no one will ever pass up an opportunity to gain a one-sided advantage by exploiting another party”. Its fundamental analytical wager is that of means-ends rationality, although this is frequently combined with an economic materialism and individualism. Instrumentalist accounts converge on themes of scarcity, greed and accumulation, and so tend to summon groups coordinated to attain the attendant benefits, for example in the idea of military battalions carrying out sexual violence as part of a strategy to seize valuable minerals. Its narrative scripts are of calculating soldier-strategists who self-consciously choose to rape, and its normative orientation envisions agents unconstrained by ethical boundaries, and thus susceptible only to direct disincentives. For instrumentality, rape is a weapon of war because it is in the direct interests of perpetrators to use it for other ends. So wartime sexual violence becomes an extension of politics in the sense that it is one tool among many adopt by self-interested actors.

Empirical support for the instrumentalist lens is drawn from the kinds of plans that embody a certain idea of masculine ruthlessness. Military documents from Bosnia-Herzegovina appear to show a conscious military calculation of means and ends, stating for example that “[Muslim] morale, desire for battle, and will could be crushed more easily by raping women, especially minors and even children”. Certainly, the cheapness of wartime sexual violence for an economic strategy of resource accumulation in the DRC is central for campaigners like Eve Ensler, who has commented that “rape is a very cheap method of warfare. You don’t have to buy scud missiles or hand grenades”. The importance of military objectives and economic goods in the narrative scripts of why men rape brings these claims close to ideas of ‘greed’ as the fuel for civil war, with sexual violence the weapon of choice in the struggle for diamonds or coltan.

Unreason signifies that which lies outside the realm of the self-conscious sovereign individual and his coherently-plotted, goal-directed action. It can imply irrationality in the sense of actions that do not benefit, or even harm, an actor, but it is not chaotic or random. Instead, it suggests the dimensions of behaviour that escape self-reflection and which defy incentives. Sexual violence in these accounts takes the form of a drive or a bond, biological or social psychological. Unreason’s analytical wagers are those of emotional and expressive being and of variegated and contested internal mental states. This gives rise to a focus on themes of trauma, affect and the (perhaps collective) unconscious. The relevant actors thus become not so much institutions or organisations as individuals led to certain acts by a confluence of events and internal urges. Its narrative scripts revolve around a psyche opaque to itself. Consequently war rapists often appear to unreason as confused, frustrated or angry. Unreason’s normative orientation addresses the conditions that perpetuate such psychological states. At the limit, this implies that rape cannot be changed by policy but must be accepted as a kind of persistent eruption. Rape here is a weapon of war because it is the result of desire and fear faced by perpetrators in brutalising situations of affect and trauma.

Unreason signifies that which lies outside the realm of the self-conscious sovereign individual and his coherently-plotted, goal-directed action. It can imply irrationality in the sense of actions that do not benefit, or even harm, an actor, but it is not chaotic or random. Instead, it suggests the dimensions of behaviour that escape self-reflection and which defy incentives. Sexual violence in these accounts takes the form of a drive or a bond, biological or social psychological. Unreason’s analytical wagers are those of emotional and expressive being and of variegated and contested internal mental states. This gives rise to a focus on themes of trauma, affect and the (perhaps collective) unconscious. The relevant actors thus become not so much institutions or organisations as individuals led to certain acts by a confluence of events and internal urges. Its narrative scripts revolve around a psyche opaque to itself. Consequently war rapists often appear to unreason as confused, frustrated or angry. Unreason’s normative orientation addresses the conditions that perpetuate such psychological states. At the limit, this implies that rape cannot be changed by policy but must be accepted as a kind of persistent eruption. Rape here is a weapon of war because it is the result of desire and fear faced by perpetrators in brutalising situations of affect and trauma.

Unreason is purest in work which stresses the expressive role of sexual violence. This is rape as an over-flowing of frustration. Among its motifs is the idea of sexual abuse as an act of group cohesion among men. It notes the frequent presence of alcohol in rape as well as racist abuse, all “typically conducted in a hands-on orgy of bloodletting”. Related justifications based on the logic of inevitable expressive unreason (‘this is just what soldiers do’) have been critiqued by Susan Brownmiller but have also been implicated in her much-quoted view that rape is “one of the satisfactions of conquest, like a boot in the face”. The most brutal and shocking acts associated with wartime sexual violence – the severing of body parts, mutilation and ‘extra insults’ in addition to rape – seem to fit with the mode of unreason, especially where they are accompanied by evidence of pleasurable release for perpetrators. Practices of sexual defilement suggest a deep disgust and horror motivating rapists, details which evoke rape as carnivalesque ‘laboratories in total domination’. Thus unreason assembles narratives of celebratory and transgressive violence, psychopathology, perverse homo-sociality and the kind of criminal opportunism that can find no justification in a financial reward.

In contrast to the exteriority of instrumentality, unreason relies on a fractured interiority. Unreason contains both the joys of war (war as game; war as the profession of the psychopath; war as festival) and behaviour in war as trauma or psychological coercion (drugs as an enforced lubricant to sexual violence; kidnapped and brutalised children; the fearful lashing out of men with guns). Consequently, its normative orientation becomes similarly fractured between an outright condemnation and palpable disgust at the pleasure taken by protagonists in sexual violence on the one hand, and a pitying recognition of trauma on the other, directing us to move away from a model in which the actors themselves feature so prominently to one which asks questions about how any human being could become so damaged as to enact these fantasies on the bodies of others in the first place.

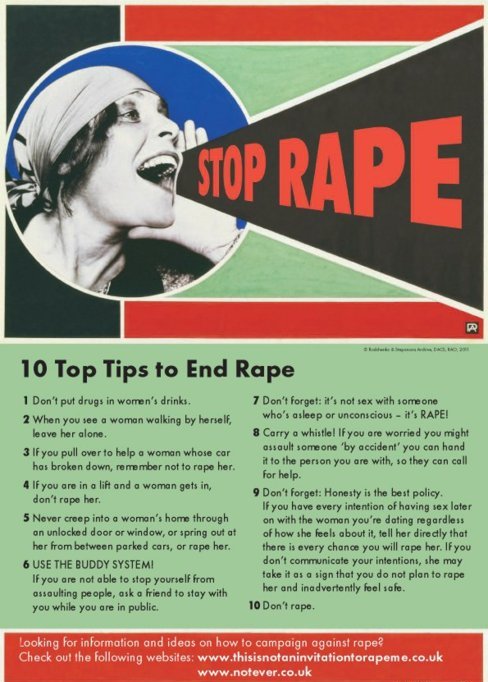

In some senses, mythology is a mediating term between instrumentality and unreason, curtailing profit maximisation within socio-cultural bounds and providing a symbolic framework for drives. But it is also much wider, embracing discourses, collective belief systems and ideologies. It includes not only doctrines and religion, but the background assumptions that are constructed through human communities, even of “rape as an identity-producing practice”. This is the view of sexual violence as shaped by cultural idioms, embodied in a habitus of masculinity or the expression of long-standing schemas of the body and of gender. Mythology’s analytical wagers are those of collective identity and the primacy of human communities. Thematically it concentrates on socially meaningful difference and subjectivities grounded in the imperatives and limits of a community or a particular institution, which then become the relevant objects and actors. Narrative scripts here frame rapists not as self-interested or as acting out personal desires, but as performers of socio-cultural ritual. Ethical and political options are thus shaped to suggest solutions in terms of changes made to the communities or institutions in question, for example through political campaigns contesting collective misogynistic beliefs or transformations in the forms of recruitment and training undergone by soldiers.

In some senses, mythology is a mediating term between instrumentality and unreason, curtailing profit maximisation within socio-cultural bounds and providing a symbolic framework for drives. But it is also much wider, embracing discourses, collective belief systems and ideologies. It includes not only doctrines and religion, but the background assumptions that are constructed through human communities, even of “rape as an identity-producing practice”. This is the view of sexual violence as shaped by cultural idioms, embodied in a habitus of masculinity or the expression of long-standing schemas of the body and of gender. Mythology’s analytical wagers are those of collective identity and the primacy of human communities. Thematically it concentrates on socially meaningful difference and subjectivities grounded in the imperatives and limits of a community or a particular institution, which then become the relevant objects and actors. Narrative scripts here frame rapists not as self-interested or as acting out personal desires, but as performers of socio-cultural ritual. Ethical and political options are thus shaped to suggest solutions in terms of changes made to the communities or institutions in question, for example through political campaigns contesting collective misogynistic beliefs or transformations in the forms of recruitment and training undergone by soldiers.

The view of wartime sexual violence as a symbolic reflection of masculinist mythology is strongest in those accounts that stress the ways in which women are treated as signs exchanged among men. Just as there is a persistent patriarchal view of women as ‘beautiful souls’, sexualised aggression can be related not so much to the particular material rewards of the act as to the imaginary role of certain women as representatives of a nation to be destroyed or a community to be punished, and of rape as a violation that only counts as a violation in some collective sense because of patriarchal norms of family and custom. Ruth Seifert, for one, accepts symbolic and institutional explanations of sexual violence but also introduces culture both as that which rape aims at destroying and as the ‘background’ to rape orgies, a set of ideas which generate their content. On this account, women may be raped “because they are the objects of a fundamental hatred that characterizes the cultural unconscious and is actualized in times of crisis”, bodies on which a particular intersubjectivity acts itself out in carnivalesque form.

Mythology need not condemn whole cultures in a way that buttresses retrograde ideas of patriarchal others or inherently misogynistic civilizational constellations. It may just as well refer to specific institutional contexts and the particular practices hegemonic there. In the mode of mythology, rape is again a weapon and a tool, but not one that belongs to individuals or which is used for accumulation or to release sexual frustration. Instead, it is a tool for a particular community. It obeys the internal requirements and limits set by a particular socio-symbolic order. Resources matter in sustaining and reproducing a group, but that does not mean that all acts in war are orientated towards that end or even that violence should be understood as an accumulatory strategy in any setting. Indeed, following the norms of a group may be counter-productive in terms of material well-being, and may involve restrictions on pleasure as well as the licence to carry out particular socially-sanctioned acts.

3. How Modes Matter

These differences in feminist accounts of war rape do not directly correspond to debates between positivists and constructivists or between qualitative and quantitative approaches to data. Nor do they merely map onto feminist empiricist, standpoint feminist or feminist postmodernist strands of theory. The contrasts between instrumentality, unreason and mythology operate at another level. As sophisticated analyses of philosophy of social science within IR have repeatedly stressed, a philosophical position on epistemology, ontology and methodology does not, and cannot, give rise to a substantive theory of how and why certain events occur. Instead, we should look to the kinds of research questions asked, the ways in which the answers are variably constructed and the emancipatory political commitments built into them. There are manifest and latent stories about what feminist analysis does, just as there are manifest and latent stories about how feminism takes on and transforms categories inherited from elsewhere, and looking at sexual violence in terms of different modes makes these more explicit.

When considered in terms of instrumentality, unreason and mythology, the tensions between different possible explanations are distributed in a new way. In some cases the modes are straightforwardly contradictory and thus force a choice between political options. For example, it has been argued both that rape happens because the militaries in question are extremely hierarchical organisations in which troops obey specific orders to rape (instrumentality) and that sexual violence is opportunistic, occurring because they are insufficiently hierarchical, leading troops to ignore orders and carry out their own wishes (unreason). In the latter example, efforts to strengthen and train militaries in conflict zones will decrease rape. In the former, such efforts will only increase the effectiveness of the masculinised war machine. And viewing the military as a site of mythology may require neither increases nor decreases in levels of hierarchy but instead point to the necessity of shifts in institutional culture.

More commonly, different modes of critical explanation will not crystallise as distinct policy options. Rather, understanding sexual violence in terms of one or other form of critical explanation will shape the priorities and forms of political intervention adopted. This is Engle’s point when she criticises some feminist activism for contributing to an understanding of war rape in terms of ethnicity and sex in a way which diverts attention from wider patterns of gender oppression. But although they are distinct, instrumentality, unreason and mythology are not straight-forwardly incompatible. Modes meet at borders of common interest: instrumentality and unreason share an interest in questions of desire, (ir)rationality, interiority and control; unreason and mythology both require an analysis of the psycho-social divide and the complex relations of subjectivity and inter-subjectivity; and mythology and instrumentality recognise the functional and collective aspects of violence.

But the resultant ambiguity is not simply that of an intellectual menu from which aspects can be chosen at whim, since the kinds of amalgamated modes of critical explanation that result differ in politically and analytically consequential ways. The overlapping yet coherent character of modes means that specific examples of rape in war can be made amenable to more than one mode of critical explanation. This poses a problem common to theory, scientific or otherwise, of how to determine which pattern of reasoning provides the most plausible account of sexualised aggression in conflict. This is the problem of the gap between modes of inquiry and modes of action, between discourses of explanation and the behaviours to which they refer, however closely they may be linked in the process of interpretation. Evaluating feminist accounts of wartime sexual violence will thus require further stages of contention and articulation.

If agreement that rape is a weapon of war can nevertheless entail radically different ideas of why wartime violence happens, what forms it takes, and what can be done about it, then understanding the character of those different ideas becomes important. Feminist accounts instantiate modes of critical explanation: modes because their grammars and styles have a structure and coherence; explanation because this coherence is not merely political or descriptive, but provides an analytical account of why certain behaviours occur and how they lead to certain events and not others; and critical explanation because they do not assume that the processes identified are deterministic and instead see them as social relations and products amenable, or at least partly open, to critique and change.

Sexual violence often seems, in its horror, to conform vividly to Primo Levi ‘s diagnosis of ‘useless violence’: “an end in itself, with the sole purpose of creating pain, occasionally having a purpose, yet always redundant, always disproportionate to the purpose itself”. There may instead be many purposes and ends, and many possible reasons, if no satisfying moral resolutions, beneath our standard accounts of rape as a weapon of war.

[1] These modes are critical explanations because in describing and explaining social relations, they also allow for a political engagement through their stress on the “non-necessary character of social relations” (in the words of Glynos and Howarth). This is itself part of the politicising character of feminist research: in none of the literature examined below is it suggested that wartime sexual violence is just a pattern of behaviour out there unrelated to our attempts to conceive of and abolish it. In this sense, feminism can be read as critical theory, centrally concerned with both reflexivity and normative categories, but not absent ‘cognitive content’ (meaningful knowledge) because of that.

Pingback: Sotalordeja, jihadisteja ja sinikypäriä – seksuaalisen väkivallan monet kasvot konflikteissa | The Ulkopolitist

Pingback: Seksuaalisen väkivallan monet kasvot konflikteissa | The Ulkopolitist