A guest post from Nico Edwards. Nico is a PhD Candidate in International Relations at the University of Sussex (UK), researching militarism and ecological injustice. She is also an Advisor to Scientists for Global Responsibility, Associated Researcher with the World Peace Foundation and author of the new report Resisting Green Militarism: Building Movements for Peace and Eco-Social Justice.

**Disclaimer: none of the people displayed in the photos are present in the text and should not be thought of as complicit with the sexual harassment discussed in the text.

Global headlines are once again seized by the outbreak of armed conflict, detailing indescribable suffering and destruction. War, it feels, is everywhere and always. To some, this means business. Many of the facilitators and profiteers of armed conflict globally attended the Defence and Security Equipment International (DSEI) in London, September 2023.

What follows is a personal story, but what it tells us about enduring systems of power and harm goes far beyond my person. That weathered feminist truth that the personal is always also political rings true still. What I experienced in the world of “defence men” – the global war elite – attending DSEI as a white woman, was highly demonstrative of the social, political and economic forces that enable and perpetuate armed violence. The personal behaviours of militarised business masculinities hold clues as to why decisionmakers keep hurtling toward global war at the expense of both people and the planet.

Setting the Scene: A Playground for Phallic Force

Happening in London biannually, DSEI is one of the world’s biggest and most important arms fairs. I went there to research military sectors’ pivot toward environmental sustainability and how to “green” warfare – a key emerging feature especially of European and North American propaganda. The event oozed of hubris. Rob, an American war simulations expert and my main interlocutor, confirmed he’d never seen such a galore of impressive weapons tech exhibitions. Indeed, several arms company reps told me affirmingly: business is booming. Spread across 100,000 sqm. Rob and I were among almost 40,000 participants from all over the world. Including the usual array of repressive, human rights abusing regimes or states involved in active warfare.

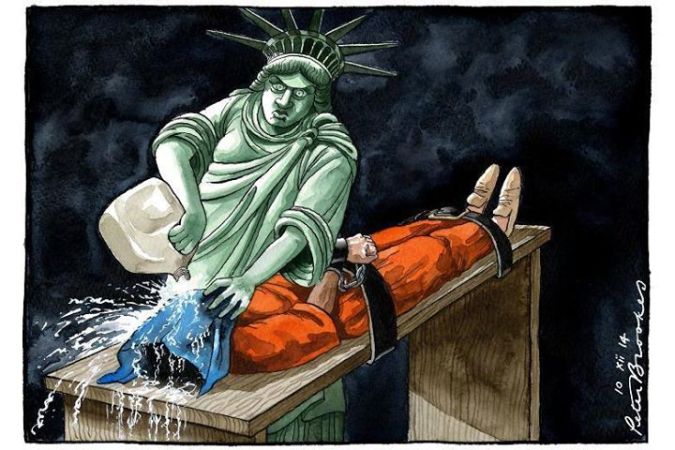

You don’t have to be a polemicist to catch how DSEI is but one big bonding ritual for predominantly white men in suits enacting their obsession with force. DSEI puts the global war elite’s drastic detachment from the real-world needs of people and planet into sharp relief. Inside the fair, “defence” and “security” materialise as glaring euphemisms for military-industrial might and titillating experiments in how to model the future of warfare in line with Hollywood fantasies of high-tech battles between good and evil. Rather than signal a dedication – however deceptive – to keeping people safe, the event felt like an inferno of white men in suits blatantly driven by that boyish excitement for tech, kinetics, heroism, beauty, sex and money. And yet, there are enough of these men in power across the globe to make it seem as if they are the realists responding to real threats.

Continue reading

‘commitment to the men and women who live around you’, ‘recognizing the social contract that says you train up local young people before you take on cheap labour from overseas.’ And perhaps astonishingly, for a Conservative Prime Minister, May promised to deploy the full wherewithal of the state to revitalize that elusive social contract by protecting workers’ rights and cracking down on tax evasion to build ‘an economy that works for everyone’. Picture the Brexit debate as a 2X2 matrix with ideological positions mapped along an x-axis, and Remain/Leave options mapped along a y-axis to yield four possibilities: Right Leave (Brexit), Left Leave (Lexit), Right Remain (things are great) and Left Remain (things are grim, but the alternative is worse). Having been a quiet Right Remainer in the run-up to the referendum, May has now become the Brexit Prime Minister while posing, in parts of this speech, as a Lexiter (Lexiteer?).

‘commitment to the men and women who live around you’, ‘recognizing the social contract that says you train up local young people before you take on cheap labour from overseas.’ And perhaps astonishingly, for a Conservative Prime Minister, May promised to deploy the full wherewithal of the state to revitalize that elusive social contract by protecting workers’ rights and cracking down on tax evasion to build ‘an economy that works for everyone’. Picture the Brexit debate as a 2X2 matrix with ideological positions mapped along an x-axis, and Remain/Leave options mapped along a y-axis to yield four possibilities: Right Leave (Brexit), Left Leave (Lexit), Right Remain (things are great) and Left Remain (things are grim, but the alternative is worse). Having been a quiet Right Remainer in the run-up to the referendum, May has now become the Brexit Prime Minister while posing, in parts of this speech, as a Lexiter (Lexiteer?).