The UN Development Programme (UNDP) has for the last 20 years pioneered seemingly innovative approaches to development that have substantially redefined the terms on which development aid is conceived, offered and spent. The publishing of the first Human Development Report in 1990 was a bold move which made a case for measuring and judging countries’ developmental status in a way which focused on quality of life indicators as well as macro-economic statistics – an idea now which is completely mainstream and commonplace amongst donor governments and development practitioners. It also proposed the notion of ‘human security‘ in 1994; a subversive response to the ‘securitisation’ agenda emerging in the wake of the Cold War which sought to broaden both the referent of security and the range of relevant concerns. It was absolutely instrumental in pushing the Millennium Development Goals agenda – an incredibly ambitious and detailed set of targets for international development practice that served to underpin widespread agreement for the expansion of development funding across donor governments.

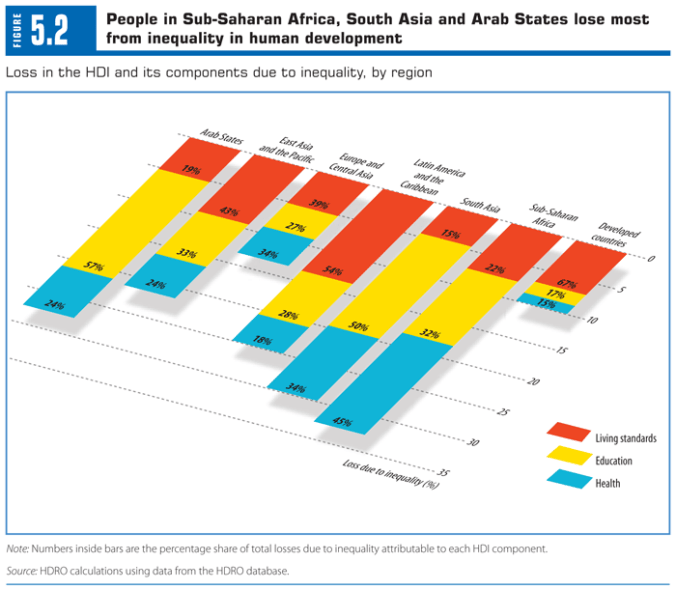

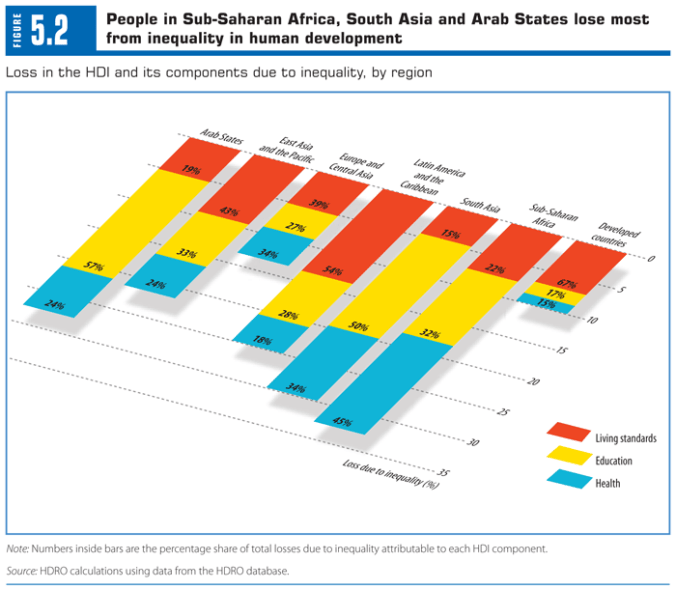

Its recent decision to measure inequality as a constituent part of development through its apparent role in determining the quality of life is, in this context, really interesting. On one level, it is indicative of the development community’s constant reflexivity – a term often used by David Williams – which recalibrates the tenor of its activities according to whatever the relevant crisis is supposed to be. Having been roundly critiqued and lambasted for the MDGs’ complicity with impoverishing neoliberal economic structures, we can read this ‘equality turn’ as the UNDP’s attempt to once more place itself on the vanguard of a more humane and responsive development agenda, moving itself away from the territory that the IFIs are starting to encroach upon.

It will be interesting to see whether and how the donors follow down this particular road. To a certain extent, the UNDP’s previous ‘innovations’ on human development, particularly with regard to adjusting for gender inequality, levels of absolute poverty and service provision, have all found various champions amongst western development agencies, all of whom have incorporated these issues seemingly deeply into their approaches to development, albeit perhaps through substantially de-radicalising the most substantive aspects of critique.

Inequality as an issue however poses a much more substantive threat to the international development agenda when pushed too far – not only does it cast doubt on the shining beaconof the self-made rich in the global South, but specifically, it starts to push against the foundational myth that ‘development abroad’ can be achieved with no corresponding change in the fortunes of ‘developed’ countries, a key threat to donor sanguinity and compliance with the UNDP’s more radical agendas. After all, if it is true within countries that vast inequalities impact on quality of life through skewing access to the goods that constitute human well-being, why would this also not be true between countries? The nonsense and yet widespread idea that some countries merely have to ‘catch up’ with others is belied by the inequality point but poses the much harder question for western countries and populaces to deal with: do I support international development enough to sacrifice any aspect of my own well-being?

As argued on an earlier post, the failure of highly-moralising development and anti-poverty agendas to deal at all with the central problem of inequality, both international and domestic, has been egregious and pervasive over the last 20 years, and looks to remain so in the future. The UNDP’s intervention is no doubt a timely one, although given the history of its more radical proposals, one which will probably be so watered down in practice as to be meaningless. Furthermore, by bringing this question within the competence of the ‘development’ policy specialists rather than engaging it as a public political question in ‘developing’ and ‘developed’ countries, the potential for getting to grips with the depth of this challenge seem remote.

In amongst a typically judicious review of Treasure Islands and Winner-Take-All Politics, David Runciman draws a suggestive comparison between the contemporary politics of financial ‘mobility’ and the legacy of colonialism.

In amongst a typically judicious review of Treasure Islands and Winner-Take-All Politics, David Runciman draws a suggestive comparison between the contemporary politics of financial ‘mobility’ and the legacy of colonialism.