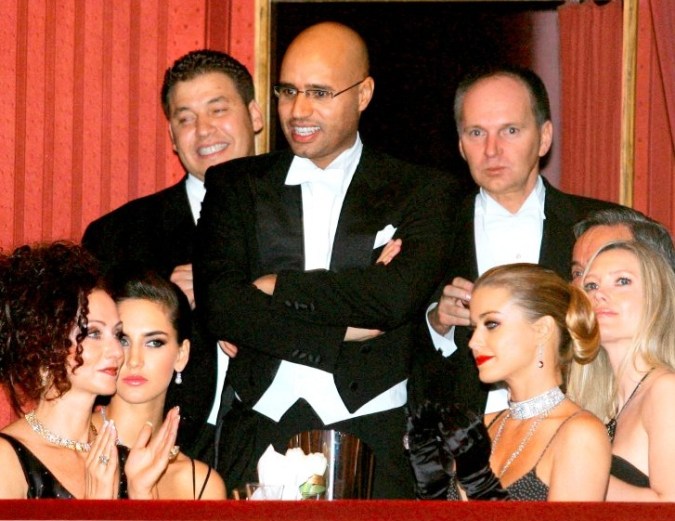

You might have thought that the realities of muscular interventionism in Libya had by now trumped the apologetics of constructive engagement. But Benjamin Barber has other ideas. His counter-attack to the nay-sayers deploys several connected themes, all of which appeal, once again, to the purported political realism of befriending Saif Gaddafi and the corresponding idealism and naivety of opposing such benevolent stewardship.

First, the attacks on the fortunate son have been “overwrought”, and have materially endangered the chances of peace by pissing him off. Second, Saif remains “a man divided, torn between years of work on behalf of genuine reform that at times put him at risk”, and thus still open to our charms. Third, he is even now working for civil society and democracy, pressuring his father to release journalists and in effect continuing the work of his foundation as a fifth column within the regime. Yes, Saif has been naughty (I’m not angry, I’m just disappointed), but his intentions are still at least partly good, and failure to achieve a better Libya through a rapprochement with him ultimately condemns we who would rather cling to the saddle of our high-horse than descend into the messy realities of progress.

The riposte is bold, and at least has the merit of maintaining the original analysis, no matter how much short-term developments may seem to degrade it. But the rationalisation, wrapped in what Anthony Barnett so aptly characterises as a ‘cult of sincerity’, falls somewhat short. The central meme, repeated by David Held, represents Saif Gaddafi as an enforcer-cum-reformer of near schizophrenic proportions. While it is (now) readily admitted that he is personally responsible for human wrongs, it also becomes necessary to insist on his internal, and magnificently cloaked, commitment to human rights. This may work for those who knew him personally and remain invested in his personal quirks and charms, but can hardly stand as a recommendation for his role as good faith mediator. As Barber himself argues (with a different intent and a suspect logic) if Saif is both revolution and reaction then he is also neither, and therefore a cipher for the projection of political fantasies.

These justifications repeat binaries of politics/morality and realism/idealism in dismissing critics (we were engaged in a calculated politics while you luxuriate in abstract ethics). Yet they also almost attempt, ham-fisted and inchoate, to escape them. After all, the defence is not that Saif is merely our bastard. Nor is it that he is a true rebel son, prepared to overthrow not only the personal dynamic of filial submission but also the political fatherhood of little green books, torture prisons and outré couture. He is said to be both, flickering and indistinct, as if this commends him. As if he can only change things because he is the natural heir of the old order. He moves between our worlds, you see. A Venn-diagrammed endorsement.