This is a post in our EU referendum forum. Click here for the introduction with links to all the contributions.

Our next guest contributor is Toni Haastrup. Toni is Lecturer in International Security and a Deputy Director of the Global Europe Centre at the University of Kent. Her current research focuses on: the gendered dynamics of institutional transformation within regional security institutions especially in Europe and Africa; feminist approaches to IR; and the politics of knowledge production about the subaltern. She is author of Charting Transformation through Security: Contemporary EU-Africa Relations (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013) and coeditor, with Yong-Soo Eun, of Regionalizing Global Crises (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

Our next guest contributor is Toni Haastrup. Toni is Lecturer in International Security and a Deputy Director of the Global Europe Centre at the University of Kent. Her current research focuses on: the gendered dynamics of institutional transformation within regional security institutions especially in Europe and Africa; feminist approaches to IR; and the politics of knowledge production about the subaltern. She is author of Charting Transformation through Security: Contemporary EU-Africa Relations (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013) and coeditor, with Yong-Soo Eun, of Regionalizing Global Crises (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

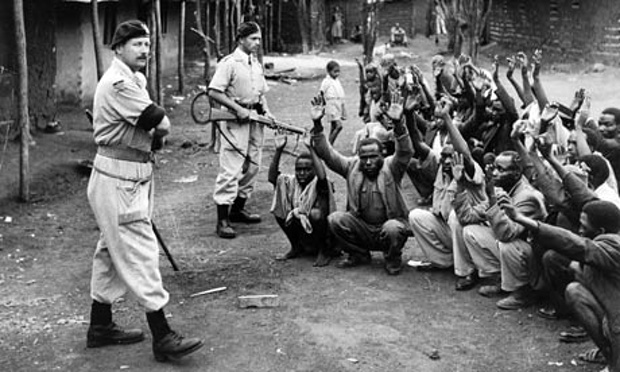

One key aspect of the EU referendum debate has been the rise of competing narratives about Britain’s role in the world inside and outside of the EU. On the Brexit side, campaigners argue that escaping the EU would revive Britain’s standing, allowing it to reconfigure relations with Europe, strengthen existing non-European partnerships, and forge new ones. These claims rest on a series of self-delusions about Britain’s capacity to unilaterally set the terms of its international partnerships. Brexiteers willfully ignore those prospective partners who say that a post-Brexit UK would be a less attractive partner. Their narrative seems to rest more on imperial delusions than solid ground – and it is hardly a narrative appropriate for a truly democratic, internationalist country.

A Part of Europe, Apart from the EU: What is Possible?

Pro-Brexit campaigners often suggest that if the UK were to leave the EU, it could fashion a new kind of relationship with Europe similar to the one Norway enjoys. Norway is viewed as a country that has maintained its sovereignty while remaining a close partner of the EU.

But of course, Norway is different. It is a thriving smaller country that is dependent on oil reserves that are much larger than the UK’s. Further, Norway negotiated a very specific entry into the European Economic Association (EEA) and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). If the UK was to depart, a relationship with the rest of western Europe especially in the context of EFTA is possible, but it is not automatic. Further, a relationship between the UK and other countries that currently exists only in the context of a regional EU relationship will have to be renegotiated, with no guarantee that the UK will indeed be better off outside the EU.

Those in favour of staying within the EU, or Bremain, thus rightly question this narrative as one that is based on uncertainty and the UK’s self-imagining, rather than the realities of the international environment. The idea that Britain would regain its sovereignty way from the EU is a myth whose consequence even the Norwegians warn against.