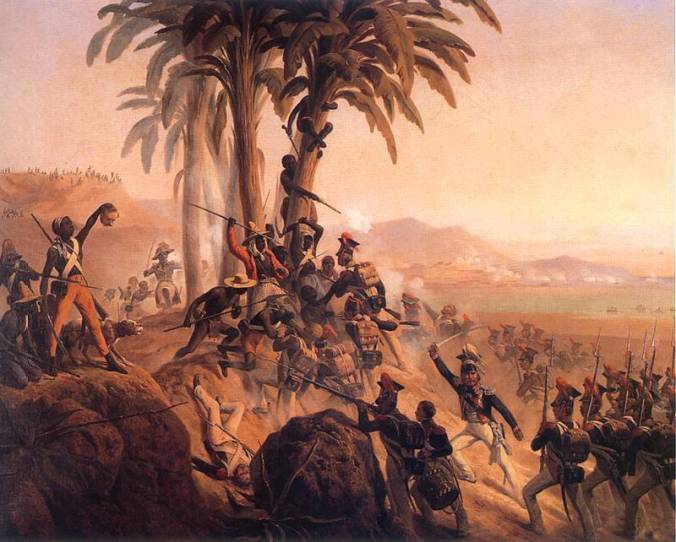

…(drumroll)… We are collectively joyous at being able to introduce a new contributor to The Disorder Of Things: Robbie Shilliam, currently at the Victoria University of Wellington and author of a slightly staggering array of critical texts (on the impact of German intellectuals on IR; the Black Atlantic in modernity; the Haitian Revolution; race and sovereignty; and the imperatives of decolonial thinking, among others). Cross-posted at Fanon/Deleuze.

At the recent ISA conference in Montreal, I participated in a lively, weighty and difficult roundtable on postcolonial and poststructural approaches to International Relations. Alina Sajed had supplied the panellists with a provocation by way of refuting Dipesh Chakrabarty’s famous injunction that Europe was the inadequate and indispensible to frame the epistemological constellations of “modernity”. Sajed challenged the panellists to debate whether Europe was in fact dispensable as well as inadequate. There was certainly a spectrum of opinions given and positions taken on the function, possibility and desirability of the relationship between poststructural and postcolonial approaches. As a form of reflection I would like to lay out some thoughts by way of clarifying for myself what the stakes at play are in this discussion and where it might productively lead.

At the recent ISA conference in Montreal, I participated in a lively, weighty and difficult roundtable on postcolonial and poststructural approaches to International Relations. Alina Sajed had supplied the panellists with a provocation by way of refuting Dipesh Chakrabarty’s famous injunction that Europe was the inadequate and indispensible to frame the epistemological constellations of “modernity”. Sajed challenged the panellists to debate whether Europe was in fact dispensable as well as inadequate. There was certainly a spectrum of opinions given and positions taken on the function, possibility and desirability of the relationship between poststructural and postcolonial approaches. As a form of reflection I would like to lay out some thoughts by way of clarifying for myself what the stakes at play are in this discussion and where it might productively lead.

For myself I do not read the Europe that Chakrabarty considers in terms of the historical expansion and exercise of material colonial power. I read it in terms of a fantasy that captures the imagination. At stake is a conception of the whys, hows and shoulds of people suffering, surviving, accommodating, avoiding, resisting and diverting the colonial relation and its many neo- and post- articulations. In this particular respect, I take Frantz Fanon’s position and agree with Sajed: “Europe” must be dispensed with. In any case, as Ashis Nandy has shown, the monopolisation of the meaning of Europe by a fascistic figure (rational, male, hyper-patriarchal, white, civilized, propertied) has required the re-scripting of the pasts of peoples in Europe and a concomitant distillation of the traditions of European thought themselves so as to accord to this fantasy figure. Europe is a fantasy through and through, but one that damages different peoples with different intensities. And those who look in a mirror and experience no significant cognitive dissonance when they proclaim “European” can still count themselves, to different degrees, as being a thoughtful protagonist in a contested human drama. For others, there is only the promise of living this drama vicariously through the thought of others. That is why “Europe” is dispensable, even though for some peoples Europe has never been indispensible; regardless, it must be dispensed with.

Let me explain a little more what I mean by all of this. Europe is first and foremost a sense of being that constructs its empathy and outreach in terms of a self whereby all who cannot intuitively be considered of European heritage are categorized into two entities. First, they might be the “other” – foils to the understanding of the self. Their emptied presence is to be filled as the verso to the internal constitution of the European self. If they are lucky, they are given a kind of non-speaking part in the drama. In fact, they usually are lucky. Much critical European thought – and certainly almost all of canonized European thought – speaks volumes about the ”other” but only so as to fill in the European “self” with greater clarity.

Second, they might be the “abject” – the entity that is impossible for the self to bear a relationship to, although even this impossibility will be instructive to the inquiring European self. Abjects, under the European gaze, are reduced to a primal fear out of which an intensity of feeling is engendered that wills the drama of human (European) civilization. Defined in excess to the other/abject, the internal life of the European self can substitute itself for humanity at large in all times and spaces, and develop itself as a richly contradictory being that overflows its meaning and significance.

I do not know whether other colonialisms predating and contemporaneous to the European project matched this audacity. And in a significant sense, it really does not – and should not – matter. After all, the lure of making comparison is the precise methodology through which the European self overflows to define all others by a lack. I do though want to hazard a particular claim at this point, which might or might not bear up to scrutiny: the prime “others” of European colonialism were the indigenous peoples of the Americas. And while we owe much to Kristeva’s work on the term, the prime “abjects” of European colonialism were the enslaved Africans bought over to the Americas.

Continue reading →

A small cascade of Millennium-related news and IR from Elsewhere. First, our very own Nick was recently elected as Co-Editor (with Edmund H. Arghand and Maria Fotou) to oversee the journal for Volume 41 (2012-2013) on the basis of a conference proposal on ‘Materialism and World Politics’ (full CfP details forthcoming soon). Second, the Millennium blog has had a facelift (ongoing tweaks to be made to its façade), so go have a look.

A small cascade of Millennium-related news and IR from Elsewhere. First, our very own Nick was recently elected as Co-Editor (with Edmund H. Arghand and Maria Fotou) to oversee the journal for Volume 41 (2012-2013) on the basis of a conference proposal on ‘Materialism and World Politics’ (full CfP details forthcoming soon). Second, the Millennium blog has had a facelift (ongoing tweaks to be made to its façade), so go have a look.