austerity |ôˈsteritē| noun – sternness or severity of manner or attitude

It was possible, therefore, to commit a sin without knowing that you committed it, without wanting to commit it, and without being able to avoid it. Sin was not necessarily something that you did: it might be something that happened to you.

– George Orwell, “Such, Such Were the Joys”

Why what have you thought of yourself?

Is it you then that thought yourself less?

Is it you that thought the President greater than you?

Or the rich better off than you? or the educated wiser than you?

I do not affirm that what you see beyond is futile, I do not advise that you stop,

I do not say leadings you thought great are not great,

But I say that none lead to greater than these lead to.

– Walt Whitman, “A Song for Occupations,” Leaves of Grass

The Politics of Austerity – Part I

This is the first in a series of posts that look at the political implications of the ongoing global economic crisis. I begin by examining the way that crisis is being used to attack the very idea of democracy through an assertion of the political imperatives of “the market” and the violation, bending and re-writing of the law by capitalist elites. I conclude by laying out how understanding the economic crisis in political terms shapes our ability to respond to it.

In the second post I’ll look at the ethos of austerity, which justifies the pain inflicted on largely innocent people, while suggesting that an affirmative democratic response to the economic crisis must begin with its own ethos, which I suggest should be an ethos of care for the world – which can provide orientation and inspiration for political struggles seeking to address the deeper causes of our current crisis. In the third post, I turn to the structures of the economy and of politics that define the current crisis, looking at the banking crisis, the bailouts, the politics of recovery/austerity and also reflecting of the structural imperatives of capitalism that led us to crisis. This, then, leads to the question of how to respond to the politics of austerity, and of what alternative actions are available to us, which is where the fourth and final post will pick up – with an affirmation of a caring ethos that supports a radically democratic economic vision.

Emergency Economics

In a previous post I briefly highlighted Bonnie Honig’s work, Emergency Politics, to examine the way that the ethical case for austerity is made; most basically, the existence of a supreme emergency, in this case economic, justifies actions that would normally be considered unacceptable. Honig’s work looks at how the appeal to emergency is used to reassert the exceptional political power of the sovereign over and against the law, with a focus on the reassertion of sovereignty witnessed over the past ten years in response to the threat of terrorist attack in the US and Europe.

Rather than accepting the necessarily intractable conflict between the power of the sovereign and the power of the law, Honig attempts to deflate this paradox by turning her attention to the always ongoing contestation that defines democratic politics, a contest over both the content of the law and the institutional embodiment of sovereign power. She suggests, then, that attending to the ambiguities of the “people”, who are both the democratic sovereign and a diffuse multitude, as well as the political element in the law – as new laws come into being through political action – enables us to avoid thinking about emergencies as moments of exception in which the rule of law is lost to the play of political power, while also acknowledging the limits of established law in moments of profound crisis. By undermining the exceptional nature of crises and emergencies Honig alters the challenge we face when circumstances force us to make choices or carry out actions we know are harmful and wrong by asking what we (democratic publics and citizens) can do to survive an emergency with our integrity in tact.

What do we need to do to ensure our continuity as selves and/or our survival as a democracy with integrity? Our survival depends very much on how we handle ourselves in the aftermath of a wrong. We will not recover from some kinds of tragic conflict. But when faced with such situations, we must act and we must inhabit the aftermath of the situation in ways that promote our survival as a democracy.

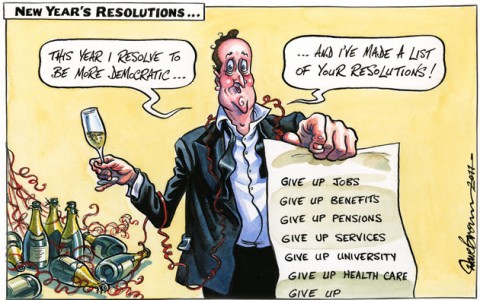

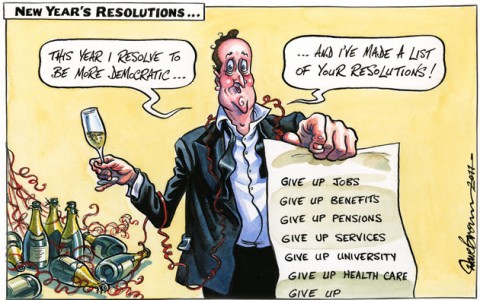

I continue to find this a useful way to understand our current economic crisis. Appeals to austerity depend upon the exceptional state created by crisis in order to justify the pain inflicted upon masses of people and the priority given to private interests (the markets, investors and bankers) over democratic publics. So, as democratically enacted laws must bow before the sovereign power threatened by exceptional attacks, so economic justice and democratic equality must bow before the commands of market forces, of economic inevitability, in this time of crisis.

The economic version of this argument is stronger still. While the space of political contestation that remains open when we accept the framing of emergency politics is limited, it does exist in the clashing of opposing sovereigns. The prospect of a substantive alternative to neoliberal economic ideology is dim, a light flickering weakly on antiquated appeals for a return to Keynesianism or watered down triangulations of the moderate-middle that sell off dreams of a just economy bit by bit – capitalist realism in action.

Honig awakens us to an important aspects of our current crisis: that “the market” is not in fact supremely sovereign, and the move to re-establish and further neoliberal policies and push through austerity measures requires an engagement in democratic politics – albeit one that undermines the notion of the public itself and seeks to use the power of the law to subvert democracy. Recognising the current crisis in these terms not only challenges us to consider how to survive our current troubles without giving up democratic virtues, it also reinvigorates and clarifies the political challenge we face. Emergency economics – with its assertion of debtocracy over democracy – is not an inevitable response to the crisis, it is a political one that we can, and should, fight against.

Continue reading →