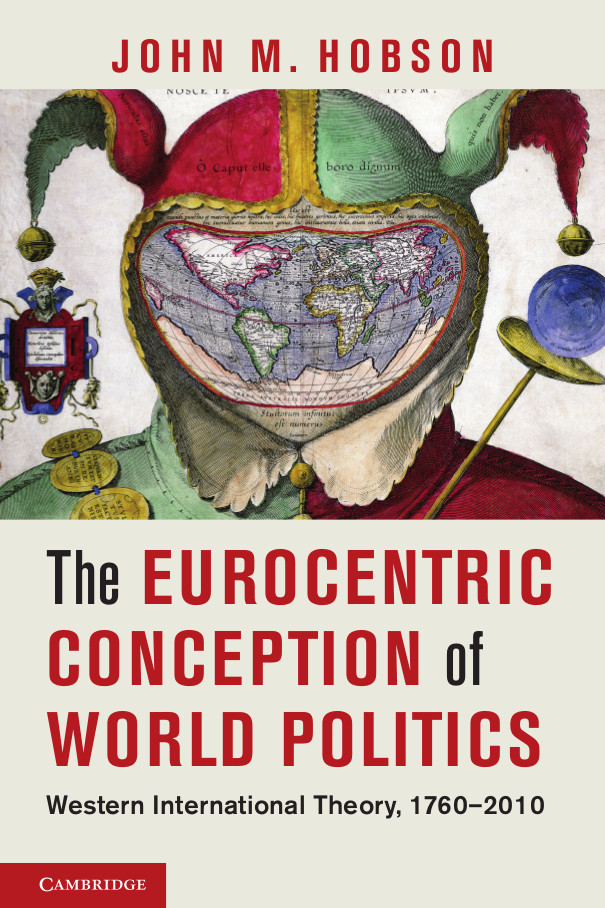

The Disorder of Things is delighted to welcome a post from John M. Hobson, which kicks off a blog symposium on his new book The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics: Western International Theory, 1760-2010. Over the next few weeks there will be a series of replies from TDOT’s Meera and Srdjan, as well as special guest participant Brett Bowden, followed finally by a response from John himself. [Images by Meera]

The Disorder of Things is delighted to welcome a post from John M. Hobson, which kicks off a blog symposium on his new book The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics: Western International Theory, 1760-2010. Over the next few weeks there will be a series of replies from TDOT’s Meera and Srdjan, as well as special guest participant Brett Bowden, followed finally by a response from John himself. [Images by Meera]

Update: Meera’s response, Srjdan’s response and Brett’s response are now up.

Introduction

As I explain in the introduction to The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics, my book produces a twin-revisionist narrative of Eurocentrism and international theory.[i] The first narrative sets out to rethink the concept of Eurocentrism – or what Edward Said famously called ‘Orientalism’ – not so much to critique this founding concept of postcolonial studies but rather to extend its reach into conceptual areas that it has hitherto failed to shed light upon.[ii] My central sympathetic-critique of Said’s conception is that it is reductive, failing to perceive the anti-imperialist face of Eurocentrism on the one hand while failing to differentiate Eurocentric institutionalism or cultural Eurocentrism from scientific racism on the other hand. As such, this narrative is one that is relevant to the many scholars who are located throughout the social sciences and who are interested in exploring the discursive terrain of ‘Eurocentrism’. These, then, would include those who are located in International Relations of course but also those in Politics/Political theory, Political Economy/IPE, political geography, sociology, literary studies, and last but not least, anthropology.

The second narrative rethinks international theory as it has developed across a range of disciplines. It stems back to the work of Adam Smith in the 1760s and then moves forwards down to 1945 through the liberals such as Kant, Cobden/Bright, Marx, Angell and J.A. Hobson, Zimmern, Murray and Wilson, onto the Marxists such as Marx and Engels, Lenin, Bukharin, and Luxemburg, and culminating with the realists who include Mahan and Mackinder, Giddings and Powers, Ratzel, Kjellén ,Spykman, von Bernhardi, von Treitschke and, not least, Hitler. After 1945 I include chapters on neo-Marxism (specifically neo-Gramscianism and world-systems theory), neo-liberalism (the English School and neoliberal institutionalism) and realism (classical-realism, hegemonic stability theory and Waltzian neorealism). This takes the story upto 1989. I then have two chapters on the post-Cold War era which examine what I call ‘Western-realism’ and ‘Western-liberalism’. The final chapter provides an overview of the changing discursive architecture of Eurocentrism and scientific racism, while also revealing how international theory has, in various ways, always conceived of the international system as hierarchic rather than anarchic. Although this is clearly a highly controversial and certainly counter-intuitive claim, it nonetheless in effect constitutes the litmus test for the main claim of the book: that international theory for the most part rests on various ‘Eurocentric/racist’ metanarratives. And ultimately my grand claim posits that international theory in the last quarter millennium has not so much explained international politics in an objective, positivist and universalist manner but has sought, rather, to parochially celebrate and defend or promote the West as the pro-active subject of, and as the highest or ideal normative referent in, world politics.

Continue reading →