The conclusion of our symposium on Chris Rossdale’s Resisting Militarism: Direct Action and the Politics of Subversion (Edinburgh, 2019), from Chris himself. Chris Rossdale is Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at the University of Bristol. His research explores how radical social movements operate as incubators of critical knowledge and theory, with a particular focus on those contesting militarism and state violence. Alongside Resisting Militarism, his recent work considers anarchist approaches to critical security studies, explores the limits of ontological security as a critical concept, and thinks with Emma Goldman about the radical potentials of revolutionary dance. He is currently editing a special issue of Security Dialogue on the relationships between militarism, racism and colonialism (to be published later this year), and writing about the Black Panthers as radical theorists of security, militarism and prefiguration. Chris is also a Director of Campaign Against Arms Trade. All posts are collected together here. And recall that the paperback of Resisting Militarism is currently discounted with use of the code NEW30 at the EUP site.

I read the contributions from Anna Stavrianakis, Erica Chenoweth, Rachel Zhou and Elena Loizidou with joy and fascination. Each has seen things in the book that have entirely eluded me until now, and all have challenged me to think again about the political, strategic, ontological and ethical arguments at play. It’s a rare privilege to have one’s work read with such generosity, clarity, and thoughtful critical attention. So, to begin, I’d like to extend my heartfelt thanks to these four brilliant scholars, and to Pablo for his wonderful work in bringing us together for this symposium.

In this spirit, I’d like to take the opportunity to think with the other contributors about how we are situated and might situate ourselves in relation to the shifting but sticky constellations of martial power that structure our world. To do so, I want to focus on the themes of pessimism, failure, prefiguration, success and violence, and think about the registers by which we have each engaged with these ideas differently. My hope is that through this we can think about the challenges we face as scholars and activists committed to resisting militarism.

Failure and Prefiguration

A theme that runs through all four responses, albeit in quite different registers, is attention to Resisting Militarism’s pessimism, manifested in my scepticism that we can ever situate ourselves outside of militarism, and accompanying critiques of anti-militarist politics that proceed with this aspiration. Loizidou appreciates the caution that this attitude brings to reflecting on movement politics, but is concerned that refusing to imagine a world beyond militarism is itself a trap. Chenoweth too laments the lack of a vision of a world beyond militarism, while also calling for a standard by which we might be able to measure the success of anti-militarist politics. Contrarily Zhou appreciates the attention given in the book not only to how anti-militarist resistance is shaped by military power, but also to the processes by which anti-militarism reproduces militarism. All three are naming a refusal in the book to locate anti-militarism outside of militarism.

Stavrianakis’ account of the same draws on a shared experience between the two of us, which I’d like to extend as a route into this. We did indeed share a delightful sunny afternoon in Brighton in the summer of 2019, during which we discussed the previous week’s Court of Appeal judgment, which – whatever else is to be said about it – did have the effect of temporarily stopping the UK government from granting export licences for arms sales to Saudi Arabia. The judgment was unprecedented, the result of years of careful and tenacious work by Campaign Against Arms Trade and others, and for all its complexities was deserving of celebration. I was there to celebrate outside the Royal Courts of Justice on the morning of the verdict. When the target of your political work is the international arms trade, there are few real opportunities to mark a win. And when there is a glimpse of possibility of limiting some of the relentless assault visited on Yemen by the UK-backed Saudi coalition, that must be taken seriously.

So, while I had settled into my more familiar mode a few days later – what Stavrianakis refers to as a sceptical curiosity – I savoured that moment. And then I had a strange experience when, at the request of my publisher, I tried to write a short blog post reflecting on the victory. I hit a real wall. Though I discuss the case and campaign at some length in the book, I couldn’t find the words to fit the moment. The book, I hope, offers plenty of resources for thinking expansively about both militarism and resistance, but it is deeply ambiguous on the topic of success. It became very clear to me that I had written a book about failure.

I mean failure not in the terminal sense, of defeat, nor as an abandonment of possibility. I am interested in what happens when we release failure from these associations. Failure can be the most intensely creative, the most insistently generative experience. At its best, failure is a mode of learning, of growing, exploring. It might engender a certain pessimism, but it need not be cynical. Successes aren’t all martial, but martiality and masculinity will tend to valorise success, to their enduring disadvantage. Left-wing social movements are better with failure, in large part because we have had so much practice. We think with and through rich repositories of lessons for improvement. You cannot look around the world as an anti-militarist activist and pretend that your organising environment is anything other than an abject failure to prevent mass violence. So yes, the book is a register of failures. High quality failures, I hope. Failures that teach, that inspire, that caution, that tell us something important about militarism shapes our world, about how we can better resist.

This said, I’m not convinced the book is straightforwardly pessimistic, nor bereft of possibilities and positive visions. There are delighted accounts of protests, actions, stunts and camps that prefigure new ways of being political subjects, curious interrogations of group dynamics that offer possibilities for subversive ways of building community, giggling renditions of jokes that unsettle and reimagine militarist rationalities. As Elena notes, the chapter on disobedience is concluded precisely with the understanding that, whatever its under-recognised fidelities to power, the craft and aesthetics of political disobedience calls forth modes of subjectivity that are genuinely transgressive.

The book is full of possibilities, attentive to the ways anti-militarist practice is subversive at both micro- and macro-levels. There is a relentless optimism, that recognises the transformative potentials of a joke, a lock-on tube, a defaced billboard, a meeting derailed through attention to its own power dynamics. On a good day, these cause havoc for governments, militaries, arms companies. What I don’t do – what I don’t have any interest in doing – is render those possibilities innocent. Everything has its underside, its entanglements. And so, I look at how the Stop Arming Saudi campaign relied on racist tropes steeped in Orientalist logics. At how martial desire structures anti-militarist tactics. At how patriarchy is reproduced in movement spaces. Everything is open to conscription. I am interested in a politics and a political imagination that remains alive to those dangers, attendant to the ways that anti-militarist politics is not external to militarism. But we need the possibilities too. A prefigurative imaginary demands that we experiment, explore, subvert, and that we fail, learn, and fail better.

In her contribution Zhou pushes me to elaborate on the approach to power and resistance at work in the book, to make clearer their mutual reliance. While the book shows that militarism and anti-militarism are dependent on one another, failing to ground this dependency in a wider analytic of power implies that this relationship might be something peculiar to militarism/anti-militarism, or (worse) that with greater reflexivity anti-militarists might be able to escape their predicament. But, as she rightly argues, there is no outside here. Coming in the other direction, and whilst appreciating the book’s critical attitude towards resistance and power, Loizidou argues that we must make at least some space for the imagination of a world beyond militarism. While I’m optimistic about the exploration of possibilities, I’m more cautious about what we might call grand visions, more complete imaginations, largely because these so easily work to obscure or naturalise entanglements with militarism. But I’m also reluctant to write those visions out completely – context is important here. The book engages with a UK-based movement that is predominantly white and middle class. It thus engages subjects who are integrated and implicated into British militarism in a host of intimate ways. So, while being mindful of Zhou’s point that resistance and power are always and everywhere in relation to one another, that relationship between resistance and power is not always the same – there are certainly contexts from which subversive anti-militarist utopias might spring. But I am sceptical of the role these might play in British anti-militarism specifically.

All of this means there is no clear account of what success would look like – at least beyond a general commitment to the overturning of imperialist white supremacist capitalist cis-heteropatriarchy. That does not mean, as Chenoweth suggests, that I think the question of whether anti-militarist politics succeeds in disrupting material outcomes is not important. It could not be more important. But the horizon of that politics cannot be a journey to the outside, to an idealized beyond-militarist futurity to which Western peace activists hold the key. The book shows that often those with the most certain belief that they can look beyond militarism are the most blind to their imbrications. Perhaps instead, we need the spirit of curiosity and humility for which Olivia Rutazibwa calls when she writes that “[t]o imagine IR anti-colonially requires from those of us at the hegemonic centre a willingness to a dislocation of power; an openness to (have others) redefine expertise and rigour, and to discomfort in the face of new knowledges” (2020: 240). We have to set our politics in opposition, and we have to explore possibilities, without knowing what the outside would look like, and with a firm recognition that those possibilities are not innocent. This doesn’t make that work futile, but it does mean that it is never complete, that there is always more to do.

Violence

In the book, I argue that there are compelling reasons to fracture the historical relationship between anti-militarism and non-violence. While non-violence and/or pacifism are often viewed as synonymous with anti-militarism, I show that many anti-militarists are in fact opposed to articulating their politics through these principles, recognising non-violence as a deeply compromised framework for radical politics. In her contribution Chenoweth criticises this move and its associated call for a ‘diversity of tactics’, framing my position as one which accepts that “political violence itself remains part of the [anti-militarist] toolkit” and suggesting that the book and certain elements of the movement thus remain attached to militarism. Disputes over non-violence are an intractable fault line in contemporary radical politics, and I won’t try to settle them here. Nevertheless, I’d like to lay out my position in a little more detail, both to clarify the argument and push the above points about power and resistance one step further.

One of the fundamental problems with dichotomous framings of movements as either violent (bad) or non-violent (good) is that, on closer inspection, even the most celebrated examples of apparently nonviolent resistance turn out to involve a combination of more and less militant tactics. Advocates of nonviolent protest fall over themselves to talk about the shining example of the US civil rights movement but are far less keen to recognise the vital role of armed self-defence, riots and sabotage in the southern freedom struggle (Cobb Jr. 2015; Osterweil 2020; Umoja 2013). Chenoweth’s own research on nonviolent movements acknowledges this, recognising that ‘categorising a campaign as violent or nonviolent simplifies a very complex constellation of resistance methods’ (2019: 4); she thus categories as nonviolent movements that are primarily nonviolent. The language of nonviolence obscures this complexity, eliding the diversity of tactics those involved in struggle have used. The role that militant tactics have often played in sustaining those movements is erased, in a way that presents contemporary movements with a vastly reduced repertoire.

However, my focus is not on the tactical merits of violent action. The book contains reflections from interviews with a number of anti-militarist activists, some avowed pacifists, others highly sceptical of non-violence. None in that latter group are interested in setting out a plan for the deployment of ‘violent’ action – certainly not at the levels that would qualify as violent struggle in Chenoweth’s work, but really not even at far more moderate levels. The political context in which such a project would be anything other than disastrous simply does not exist in the UK. Those activists’ scepticism of non-violence is not connected to the need for violence, but rather to the regulative role played by non-violence as a discourse that polices the scope of legitimate resistance.

We’re on unstable territory here. Violence as a concept is notoriously slippery, and the nature of violence cannot be determined prior to context. In acknowledging this, Chenoweth makes reference to the Weather Underground, which reminds me of a letter written by the famous pacifist peace activist Daniel Berrigan to those same activists. In it, he chides these young white radicals for their bombing campaign, “the risk always being very great that sabotage will change people for the worse and harden them against enlightenment” (2003: 244). However, in that same letter he pauses to distinguish the actions of the Weathermen from those of the Black Panthers and the Vietcong; the latters’ resistance to empire, the celebrated pacifist notes, cannot properly be classified as violence. Berrigan’s dramatic appeal to context invokes an understanding of violence that can only be determined in relation to power. He writes in the important tradition of pacifist thought which refuses steadfastly to dictate the terms by which the oppressed may confront their oppressor.

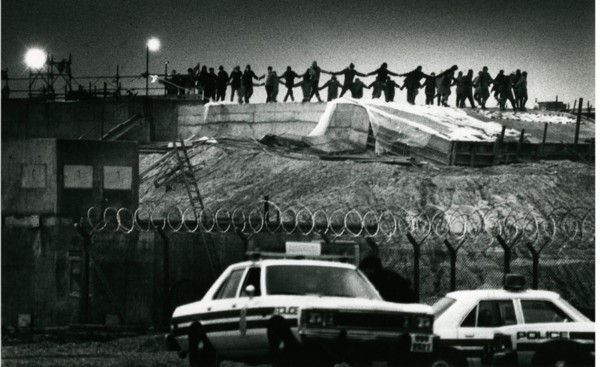

That ambiguous character of violence is a constant challenge for ‘non-violent’ movements. I’m fond of a story that emerges from Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp. In the early days of the camp, which was established outside RAF Greenham Common in 1981, activists refrained from cutting through the fence in order to gain entry into the base, because consensus could not be reached about whether this contravened the ethos of nonviolence. This changed in the summer of 1983 when a group decided to cut the fence and enter the base; over time the feeling of the camp shifted to the belief that cutting the fence could be regarded as an act of ‘creative nonviolence’ (Roseneil 1995: 106-7; Young 1990: 18). To the movement’s enduring credit, most British anti-militarists – even those who are staunchly committed to non-violence – consider the physical destruction of arms trade facilities to be a non-violent and perfectly acceptable act.

As I said, my interest is less in holding open the space for the tactical deployment of violence, than with the regulative role played by foregrounding nonviolence. This is largely because the ambiguity in the concept which permits the nuanced and creative readings of Berrigan and the women of Greenham Common also permits intimately harmful articulations of non-/violence – from both movements and the state.

There are two major issues here. The first is that the vernacular conceptions of non-violence at play within movements often bear limited resemblance to the complex and nuanced accounts found in more philosophical works. Activist accounts tend to place a high degree of focus on some forms of violence, while remaining blind to or actively complicit in others. In my experience, those movement spaces which are most vocally insistent on non-violence place overwhelming focus on the presence or absence of physical force, while often remaining unaware of or indifferent to racist, sexist, ableist practices within their community. This relates to the points about militarism above; alarm bells ring when anyone posits an outside to violence that they are able to occupy. The sense of good conscience this move conveys and feeds can easily be inimical to the recognition and critique of violence. As pretty much anyone who has been involved with movements will attest, there are good reasons not to get too optimistic when told that a group, movement, or space will be ‘non-violent’; there is every chance that this is a space that is deeply unreflective about its internal power dynamics.

The second problem lies in the role that non-violence plays in the policing and fracturing of movements. Chenoweth notes that it is generally seen even by pacifists as ‘fundamentally counterproductive’ to publicly denounce other activists for not adhering to nonviolent practices. This is usually true, though there are many exceptions; for instance, Kate Hudson, currently General Secretary of CND, publicly denounced Black Bloc activists following a demonstration in Strasbourg, stating that “[t]hese people are no part of our movement. They are an obstacle to effective resistance and must be isolated and recognized for what they are: wreckers whose actions turned the mass of people against our campaigns” (cited in Cockburn 2012: 147). However, the issue here is more substantive than such occasional breakdowns.

Each and every time we reposition nonviolence as the gold standard of a movement’s virtue, and reinforce its status as the shibboleth for acceptable political action, we contribute to state-led strategies of repression and delegitimation which target movements as soon as they mount any meaningful kind of challenge, whatever their conduct. A primary device here is the distinction between well-behaved, non-violent protestors, and violent spoilers. The resulting police repression falls most squarely on those who are always already marked as violent, even if they adopt the most careful non-violent posture – this, of course, is the state’s mirror to Berrigan’s contingency. The aggressive policing of last year’s Black Lives Matter protests in the UK, contrasted with the light-touch approach to Extinction Rebellion demonstration, was one amongst countless reminders that white supremacy shapes epistemologies of violence and non-violence.

My critique here is not of the use of what are seen as non-violent tactics themselves (the book is full of loving descriptions of many of these), but the crowning of non-violence as the ultimate standard of movement conduct. Not only does this obscure more complex histories of political liberation; it implicitly confers far greater legitimacy on those who are able to position themselves and be recognized as acceptably nonviolent, while setting the terms for the exclusion and repression of those who are not. And while the quote from Hudson above is a good example of how activists can actively participate in that (violent) process, the extant hegemony of non-violence discourse sets it always already in motion.

Anti-militarist politics are fundamentally concerned with disrupting the social processes through which violence is made possible. And a prefigurative approach to anti-militarism insists that we explore alternatives to violence. But if we do that in a manner that maintains fictions of escape, that enables violent policings of the distinction between violence and non-violence, or that reduces violence to physical force, then we are left with an ultimately conservative standard – one that leaves intact much of what we might reasonably call violence. So, I really want to push against the terms the claim that ‘political violence remains part of the toolkit’ and that I ‘accept a limited amount of violence’. There is no outside of violence here. The choices aren’t between violence and non-violence in any straightforward sense, but about the disposition we hold – as individuals and as movements – towards the inescapable but transformable violences of our condition. We should be firmly focused on resisting martial violence – but not from the seductive innocence of ‘non’-violence.

Strategic disagreements of course remain. Refusals to commit to non-violence shut down some potential alliances. The insistence on commitments to non-violence shuts down others. While I am personally more optimistic about the networks and solidarities that can be forged freed from the declarative terrain of non-violence, my more fundamental concern is with the kinds of politics and relationships with power we set in motion through organizing. It’s not enough to form the bigger coalition if the fundamental terms of that coalition are an accommodation with structural and state violence. The task for radicals is not to operate within the contours of what power is, but to reimagine what power can be; to seed new possibilities even as we confront the violence of the world we inhabit and which inhabits us. At its best, British anti-militarism does just this in so many beautiful ways. I hope that the book too is some small contribution to this task.

References

Berrigan, D., 2003. ‘Letter to the Weathermen’, in J. James, ed., Imprisoned Intellectuals: America’s Political Prisoners Write on Life, Liberation and Rebellion, Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 242-7.

Chenoweth, E. and M. Stephen, 2011. Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, New York: Columbia University Press.

Chenoweth, E., 2019. ‘Online Methodological Appendix Accompanying “Why Civil Resistance Works”, https://www.ericachenoweth.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/WCRW-Appendix.pdf

Cobb Jr, C. E., 2015. This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible, Durham: Duke University Press.

Cockburn, C., 2012. Antimilitarism: Political and Gender Dynamics of Peace Movements, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Osterweil, V., 2020. In Defence of Looting: A Riotous History of Uncivil Action, New York: Bold Type Books.

Roseneil, S., 1995. Disarming Patriarchy: Feminism and Political Action at Greenham, Buckingham; Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Rutazibwa, O., 2020. ‘Hidden in Plain Sight: Coloniality, Capitalism and Race/ism as Far as the Eye Can See’, Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 48(2): 221-241.

Umoja, A. O., 2014. We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance in the Mississippi Freedom Movement, New York: New York University Press.

Young, A., 1990. Femininity in Dissent, London and New York: Routledge.