The last but not least in our commentaries on Katharine Millar’s Support the Troops: Military Obligation, Gender, and the Making of Political Community (with a reply by Katharine to follow tomorrow). Ellen Martin is a PhD candidate in the School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies (SPAIS) at the University of Bristol. Her research is critiquing military power in Britain, with a particular focus on the ways in which the British public diversely perform militarism in their everyday spaces. She is interrogating the discourses employed by military charities to question how these organisations contribute to making war and violence possible. She is also exploring how the British public engages with these discourses, and militarism more broadly, because the ways in which militarism manifests as normal and desirable to British people is central to its operation. With the aim of interrogating and destabilising military power, her research contributes to ongoing conversations in feminist IR and Critical Military Studies. Chris Rossdale is Senior Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at the University of Bristol. They write about social movements, rebellious politics, and militarism and state violence, including in Resisting Militarism: Direct Action and the Politics of Subversion. They are interested in the relationship between political struggle and critical theory, and their current research considers the arms trade within the context of police power and abolition and explores the contested political status of ‘rebellion’ in the contemporary era.

Support the Troops opens with an anecdote about the small town in Canada where Katharine Millar grew up. In 2001 Canada deployed forces to Afghanistan, and a number of enlisted young men from the town found themselves unexpectedly sent to war. Their families gave out yellow ‘support the troops’ ribbon magnets for local people to put on their cars. Millar recalls her parents, sceptical of the intervention, navigating the expectations accompanying the ribbon and its awkward invocation. They displayed the ribbon out of some sense of obligation and genuine care for the local boys overseas, while being uncomfortable with its implications, and seemingly content to let the ribbon disappear once the temperature had fallen.

The book does the impressive job of taking these quotidian gestures of solidarity and tying them to the imperial violence at the heart of the liberal social order. Taking a particular but persistent social discourse, it traces the historical emergence of an imperative that has become central, even foundational, to liberal politics. Elegantly and incisively, Millar shows the workings of the discourse as it has diffused through and become a standard of legitimate speech within contemporary political life. ‘Support the troops’ emerges as a “gendered, racialized logic of violent political obligation” (167) that is ideally positioned to manage civilian anxieties following the end of conscription, while carefully transferring questions of complicity and empire into expressions of care and solidarity within the state. The discourse conceals the harms of war while awkwardly reproducing the liberal community. Making its argument with clarity and force, and showcasing the power of rigorous feminist poststructural analysis, the book is a landmark intervention in scholarship on liberalism, war and violence.

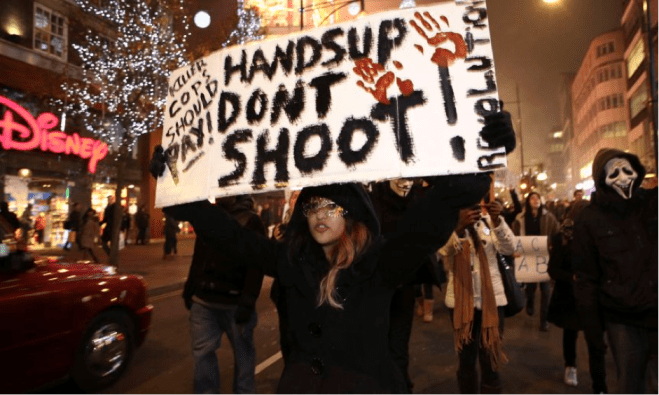

Millar lays a particularly important challenge for anti-war politics. While many expressions of the imperative to ‘support the troops’ are delivered with a clear desire to promote wars, the book shows that the discourse is also central to anti-war politics. As demonstrated by their calls to ‘support the troops: bring them home’ and ‘support the troops, not the war’, opponents of contemporary wars are compelled to frame their opposition in terms of support for the troops. Drawing on her extensive study of discourse from newspapers, state documents and NGO websites, Millar argues that almost half of the incidences of the support the troops discourse in the UK and US come from an anti-war position. It emerges as an apparently necessary element of attempts to criticise wars, in a manner that reveals the discourse as a condition of intelligible political speech and reasonable dissent. If you want to speak politically, you must support the troops; if you don’t support the troops, you’re not a meaningful part of the political community. The problem here is that ‘support the troops’ is an inherently martial discourse. It reproduces the troops as the ideal citizen, solidifies the martiality of the liberal order, and reproduces the hierarchy between ‘our’ troops and others suffering in war (often at the hands of ‘our’ troops). In this respect, anti-war politics faces a trap: frame opposition to wars through support for the troops, and so reproduce the liberal martial order even in the midst of opposing a particular war; or don’t, and be expelled from the terrain of reasonable political speech.

Continue reading