In the face of a UK higher education marking boycott due to start in 11 days time, universities have come forth with a new pay offer. Having unilaterally imposed a 1% rise (read: real terms cut) for 2013/14, they are now proposing 2% for 2014/15, with a small bonus for those on the lowest band to bring them up to a living wage level (at Sussex, that’s an increase on the existing annual pay of £13,621). A consultative ballot is open to union members, and the boycott is delayed. It seems likely that there will be appetite for the deal, given the general tone of despondency and how drained staff are by repeated small scale actions and by mounting work pressures. There had, after all, been doubts that a boycott could compete with aggressive tactics from management (including threats to deduct full pay from anyone who participated in the boycott).

We might be emboldened by this concession from UCEA (the employers’ association). It shows, as more ‘militant’ elements had predicted, that greater returns would be achieved with the threat of a marking boycott than with all the 2-hour and single day strikes put together.[1] A first offer, before the boycott has even begun. Could we not win more than these peanuts (only just a real terms increase, following five cuts in a row, going by Consumer Price Index)?

Sort of.

Today’s union communication stresses (twice) that the 2% is a “full and final offer” from universities to their staff. So after 11 months of dispute over last year‘s pay deal (the one they forced on us despite no agreement having been reached), UCEA are insisting that this is the final offer on the next round of negotiations, the ones that have only just begun. In other words, this is not a contribution on the existent dispute at all, but a foreclosure of negotiations on what comes next. The derisory 1%, and the manner in which it was enforced, is taken as read. The 2% (although less of an insult than offers since 2009) maintains the trend of wage suppression.

That is not, in and of itself, a reason to reject the offer. Members and branches will have to make their own judgements on what kind of support can be garnered for boycott action. But the trends are not in our favour. It is an understatement to say that UK higher education is under pressure. The government is pursuing fundamental changes through non-legislative means (as David Willetts says, civil servants are having to be “ingenious” in their methods), in a way that is bound to increase inequality in the system. Several elements of that strategy (the entry of private providers, the maintenance of research funding, the state’s management of student debt) are now in crisis, putting us on a trajectory that may even lead to further fee increases.

Universities, although surely guilty of advocating for the very changes which are now causing mild panic, nevertheless find themselves having to play the middle manager, responding to dictates from above and contempt (sometimes revolt) from below. Their fears are quite public (if subject to some massaging). There’s those severe cuts in teaching and research grants. The replacement funding of £9,000 in fee income per UK student per year is being eroded in real terms by inflation every year. Because student-consumers now expect more, there is a widely-felt need to invest in new buildings and facilities (this is the big are of expenditure growth for the sector). Then there’s uncertainty over student numbers, exacerbated by rapid and unexpected shifts in funding through HEFCE, and the spectre of private providers of various kinds.

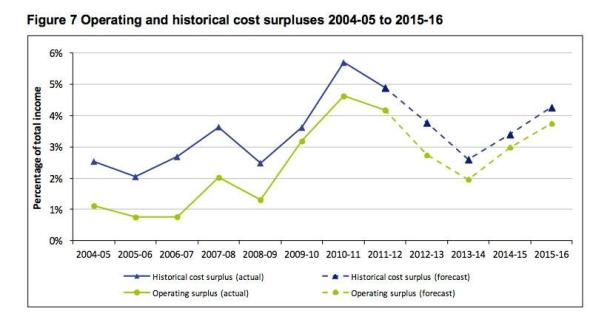

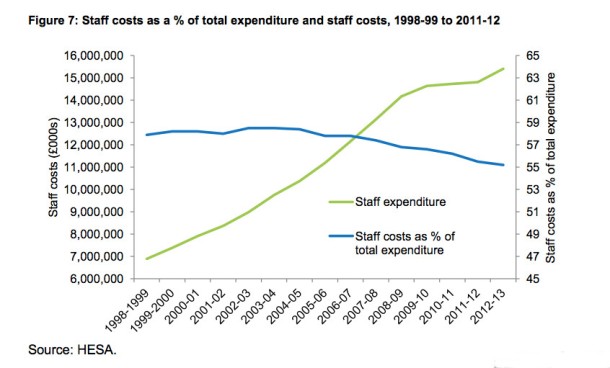

This may seem to support UCEA’s cries of inevitability over pay. But consider two facts. First, surpluses have not fallen. Indeed they are expected to be higher by 2015 than they were in the period up to 2010. This has been achieved at least partly by having staff do more (longer terms, larger class sizes, and the like). Second, staff costs (as a percentage of overall expenditure) have consistently declined since the early 2000s. Relatively new entrants (like me) are getting a much reduced pension (another case of hyperbole being used to force down pay and conditions). Universities claim that their salaries remain “competitive” relative to other sectors. It is noteworthy, if completely unsurprising, that this is particularly so for the managerial class, who appear to receive about 20% more in the higher education sector than their counterparts elsewhere (see pg. 10). But where other outgoings are increasing, and incomes decreasing, the relative health of the sector is being maintained by pay suppression.

Here, for example, is HEFCE’s assessment. Almost speaking plainly:

The sector has shown over recent years that it can deliver efficiencies. For example it has reduced its cost base, with pay costs being curtailed after a period of strong growth. These efficiency measures have helped support the current financial performance of the sector. It will be important for the sector to maintain this efficiency drive in order to deliver long-term sustainability in the future.

Efficiency must be maintained. Pay must continue to fall in real terms. Your living standards must stagnate, and ideally fall, until some as-yet-unknown equilibrium point is reached. This is the solution as far as universities are concerned, and they are telling us so. The conundrum for them is real enough, but its resolution at the expense of university workers is not natural, or automatic. It is a political fact, and we can change it. Our students are able to collectively express their solidarity, and to grasp the realities of what is going on better than some colleagues. For our part, there must be a limit to hiding behind our (quite genuine) concern with preserving a positive learning experience, or our (much less legitimate) attachment to the idea that academics are too privileged as workers to make a fuss. Sure, we’re tired of tilting at gristmills, and legitimate disputes can be had over strategy, but the undermining of university labour is not about to lessen. Increments may soften the blows for those already inside the ivory bungalow, but the door is swinging in everyone else’s face.

[1] ‘Militant’ is a somewhat ludicrous term in this context. Pretty much everyone agrees on the following: (a) staff pay cannot, and should not, fall indefinitely; (b) the current system is at real risk of costing more (to the state) to deliver less (in teaching and research); (c) government-mandated disruption of higher education will lead to significant harm for a whole class of institutions, and may well do serious harm to overall research performance and other indicators of grandeur; and (d) there is significant bloating at the top end, and increasing resort to precarious labour. The people that feel that something should be done about that are only really expressing a rather common-sensical analysis, one which reflects in large part a vision of the university system borrowed from just before the great financial crisis.

Reblogged this on Progressive Geographies and commented:

A good analysis of the latest developments in the UK higher education pay dispute.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on discurrere and commented:

One of the most clear-headed assessments of the current situation re: staff pay I’ve read

LikeLike

Pingback: Let’s Talk About Work… Could discussions about work also be a useful pedagogical tool? | Queen Mary Against Casualisation