This year is the seventieth anniversary of Winston Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech, a.k.a. “Sinews of Peace,” a.k.a., the Fulton address, which means that we will soon be hearing all about it once again. The speech is central to the iconography of the Cold War, of anti-communism, and of Anglo-American specialness. Countless historians, biographers and rhetoreticians have examined almost every aspect of it: when and where it was written, whether it was pre-approved by others, including President Truman, and, indeed, how it was received. On the last point, we know that the speech was met with a mixture of cheers and boos. The reactions tended to be politically and ideologically determined. Conservative politicians and the media praised the speech for its realism about the nature of the postwar settlement: at last someone had the courage to publicly say that the victor nations could not forever be friends. In contrast, most liberals, socialists, and communists condemned the speech as inflammatory. With so many hopes pinned to the newly created United Nations Organization (UNO), the last thing the world needed was geopolitical tension between the Western powers and the Soviet Union, they argued. But that was not all. Some leftists went further still. Churchill’s notion the Anglo-American “special relationship” and “fraternal association” constituted the ultimate sinew of world peace smacked of racial supremacism, they said.

Race

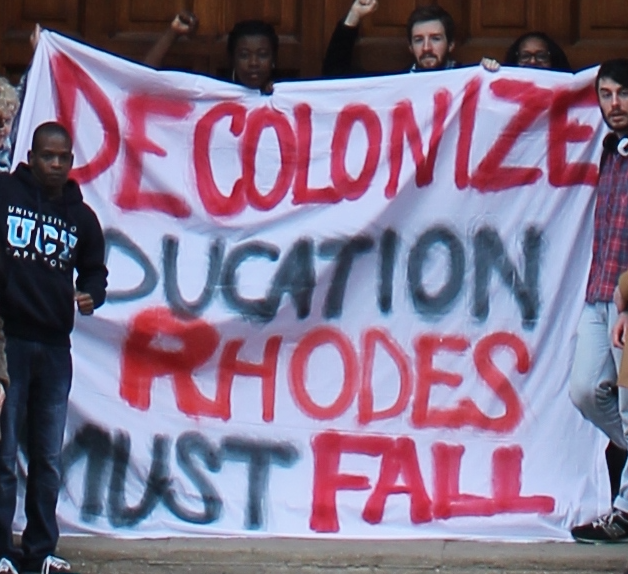

The Dissonance Of Things #5: Decolonising the Academy

In this month’s podcast I’m joined Dalia Gebrial from Rhodes Must Fall Oxford and two stalwarts of TDOT, Meera and Robbie, to discuss ‘Decolonising the Academy’. We take a look at the Rhodes Must Fall campaign and its implications for understanding the relationship between higher education, coloniality and ‘race’. We also ask why is my curriculum white? What can be done change the way in which knowledge is produced and taught in universities? Finally, we explore how decolonising the academy might relate to anti-colonial and anti-racist struggles taking place outside of the university.

Listen via iTunes or through the Soundcloud player below.

The Black Pacific: Thinking Besides the Subaltern

The first in a forum on Robbie’s recently released The Black Pacific: Anti-Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections (Bloomsbury, 2015). A number of commentaries will follow in the coming week.

May 1979. A Black theatre troupe from London called Keskidee, along with a RasTafari band called Ras Messengers, land at Auckland airport, Aotearoa New Zealand. They have been invited by activists to undertake a consciousness-raising arts tour of predominantly Māori and Pasifika communities. They are driven almost immediately to the very tip of the North Island. There, at a small hamlet called Te Hāpua, Keskidee and Ras Messengers are greeted by Ngati Kuri, the local people of the land.  An elder introduces his guests to the significance of the place where they now stand. Cape Reinga is nearby, where departing souls leap into the waters to find their way back to Hawaiki, the sublime homeland. The elder wants to explain to the visitors that, although they hold an auspicious provenance – the Queen of England lives amongst them in London – Ngāti Kuri live at ‘the spiritual departure place throughout the world’. The elder concludes with the traditional greeting of tātou tātou – ‘everyone being one people’. Rufus Collins, director of Keskidee, then responds on behalf of the visitors:

An elder introduces his guests to the significance of the place where they now stand. Cape Reinga is nearby, where departing souls leap into the waters to find their way back to Hawaiki, the sublime homeland. The elder wants to explain to the visitors that, although they hold an auspicious provenance – the Queen of England lives amongst them in London – Ngāti Kuri live at ‘the spiritual departure place throughout the world’. The elder concludes with the traditional greeting of tātou tātou – ‘everyone being one people’. Rufus Collins, director of Keskidee, then responds on behalf of the visitors:

You talked of your ancestors, how they had taken part in our meeting, and I do agree with you because if it was not for them you would not be here. You talked of our ancestors, taking part and making a meeting some place and somewhere; the ancestors are meeting because we have met. I do agree with you.

But Collins also recalls the association made between the visitors and English royalty, and there he begs to differ: ‘we are here despite the Queen’. Then the Ras Messengers begin the chant that reroutes their provenance from the halls of Buckingham Palace to the highlands of Ethiopia: “Rastafari come from Mount Zion.”

the visitors and English royalty, and there he begs to differ: ‘we are here despite the Queen’. Then the Ras Messengers begin the chant that reroutes their provenance from the halls of Buckingham Palace to the highlands of Ethiopia: “Rastafari come from Mount Zion.”

This meeting is emblematic of the story that I tell of The Black Pacific wherein Maori and Pasifika struggles against land dispossession, settler colonialism and racism enfold within them the struggles of African peoples against slavery, (settler) colonialism and racism. Sociologically, historically and geographically speaking, these connections between colonized and postcolonized peoples appear to be extremely thin, almost ephemeral. But those who cultivate these connections know otherwise. How do they know?

The Stories We Tell About Killing

The third piece in our forum on Economy of Force (following Patricia’s opening and Pablo’s piece on patriarchy), and the first contribution to The Disorder of Things from Jairus.

Narrative: The central mechanism, expressed in story form, through which ideologies are expressed and absorbed.

– Glossary, U.S. Army Field Manual 3-24

Patricia Owens Economy of Force is, to date, the most important book that has been written on counter-insurgency. To put it another way, Economy of Force is the first book written with the sobriety of distance from the necessary but often polemical responses to Human Terrain and the high-profile ‘anthropologists’ of war in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The shortcoming of these earlier responses was the tendency to treat contemporary efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq as somehow new. Lost in the flurry of shock over academic involvement in warfare was the understanding that social theory has, in some sense, always been at war. It is this last point that Owens’ book really excels at theorizing. Unlike other explorations of counter-insurgency that emphasize the ‘weaponization’ of social theory and anthropology, Owens locates counter-insurgency as an outgrowth of liberalism and its governance of the social, specifically the domestic. This difference is vitally important. In the work of Roberto Gonzalez and others, we are left with a sense that anthropology and social work could be demilitarized. However, the genealogy of ‘home economics’ given to us by Owens’ suggests that the very concept of the social is rife with the desire for order, which is often established by violent means.

This places the first part of Owens book alongside Michel Foucault’s three biopolitics lectures, in particular Security, Territory and Population, as well as Domenico Losurdo’s Liberalism: A Counter-History. In their own way these works attempt to reconstruct the philosophical and political history of liberalism as beginning with the violence of racial and economic ordering, rather than seeing liberalism as having fallen from grace as a result of the temptation and corrosive effects of empire. Owens, Foucault, and Losurdo all find liberalism’s logic of governance to be in the form of what Foucault famously called ‘war by other means.’ What distinguishes Owens’ work from Foucault and Losurdo is that she follows this line of logic through to the particular formation of a liberal way of war called counter-insurgency. Owens’ foregrounding of counter-insurgency is a much needed corrective to Foucault’s conclusion in Security, Territory, and Population, where he argues that external relations in the state system of Europe were characterized by balance of power politics. Entirely absent in Foucault’s development of the concept of race war in Society Must be Defended and Security, Territory, and Population is the particularities of European imperial and then colonial enterprise. This becomes even more apparent in the final lectures The Birth of Biopolitics, in which the brilliant and prescient account of the rise of neoliberalism in the U.S. leaves out entirely the anti-black racism that animated the war on the welfare state. Owens’ more internationally situated account does not ameliorate all of these shortcomings, but does put us on the road to doing so. In fact, her genealogy of the domestic is not about refining our understanding of the social in social theory, but about showing how essential and under-theorized the domestic is in the field of International Relations, which relies essentially on the difference between the foreign and domestic.

Let’s Talk About the “Ugly Briton”: Shashi Tharoor on Winston Churchill

October is always a good time to catch up on one’s correspondence from July. “FYI,” noted a friend though FB’s messaging system, linking to this:

The video’s title, “Dr Shashi Tharoor MP – Britain Does Owe Reparations,” sums it up. The other videos from the same debate event are worth watching, too, but Tharoor’s is quite simply a must-see for anyone interested in the British Empire. Indeed, you have probably seen it already. With 3 million views, 6000+ comments plus what seem to be hundreds of reactions by all kinds of people in all kinds of media of communication, this one 15-minute video alone can legitimate Oxford Union Society claim’s that it aims “to promote debate and discussion not just in Oxford University, but across the globe.”

Why is it that Oxford Union struck social media gold with this debate but not with some others (“socialism does (not) work,” anyone)? Even if it is safe to assume that “many” people would be familiar the reparations argument in general and even that “some” would be familiar with Britain’s reparations to the Maori, the fact is that “no one” had given a fig about the case for Indian reparations [1]. My scare quotes are meant to signal that these quantifications are relative. It was a century ago that Dadabhai Naoroji, known to some as the Grand Old Man of India, argued that “immediate” self-government, a.k.a. swaraj, would constitute Britain’s “reparation”. But this is precisely the point: reparations-talk becomes itself only when subjected to a sufficient degree of metropolization or mainstreaming [2]. White academics like Boris Bittker started paying attention to the legal argument for “black reparations” only in 1969, after James Forman famously stood up in a New York City church to argue that white churches owed a lot of money to a lot of people.

The Status of Syrian Nationals Residing in Turkey

Preface.

I have written this blog post about three weeks ago and have been sitting on it, reflecting about it since then, I was not sure if I wanted to write yet another piece on the “Syrian refugees”. But yesterday, we all woke up to the images of two young children lying on the beach lifeless around Bodrum, Turkey, and having read some of the posts available, I felt the need to post this. This is not a happy or “cool” post. This is a post about dire conditions and technicalities on the status of Syrian nationals living in Turkey, and it should be seen as a plea for assistance, and action.

The children in the pictures were Aylan Kurdi, 3 years old, and his brother Galip Kurdi 5, who drowned along with their mother Rehan Kurdi, on their way to Kos, Greece. They were from Kobane, trying the irregular route after their application for private sponsorship was refused by the Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), and presumably the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB) of Canada this summer.

As an expectant father, and a human being, those pictures are too brutally heartbreaking for me. They are too real, yet unfortunately they are not exceptional or extraordinary. I was unable to look at the pictures for more than a second, and I don’t think I can ever get to share them or look at them again. Elsewhere on the Visual Cultures Blog, @MarcoBohr makes the point on how we can only confront the inhumanity of the situation by confronting such pictures directly, but I just can’t get myself to look at them again, so I am not posting them or really talking about them in this post. Instead, I look at some of the reasons (structural, institutional, situational) that pushes people to seek such a risky route out of Turkey. The images, in tandem with all those individuals dying in the Mediterranean, en route to Europe, represents a moral/humanitarian crisis and demonstrates the hollowness of the so-called “normative power Europe.” The European Union, US, Canada, Australia, and every other capable country – including the Middle Eastern countries – must be ashamed of their actions, or the lack thereof, in addressing this crisis. As scholars, individuals, and human beings we must not just read about these deaths, we must whatever we can stop others from dying the same way.

Knowing Like A Jinetera

The last commentary post in our forum on Megan’s From Cuba With Love, following contributions from Megan herself, Rahul, Dunja Fehimovic and Nivi. Megan’s rejoinder will be up imminently.

So near and yet so foreign! declares the advert. Intimate and exotic, Cuba as a repository for fantasy and self-discovery, the neighbour with the mixed-race charms, the imagined nation Cindy Weber once analysed so relentlessly as “the near colony and certain feminine complement” of the United States. Megan’s new, and first, book – From Cuba With Love – exposes the same kind of dynamic, although from a different standpoint.[1] Hers is a near-seamless blend of reportage and feminist IR, moving from autobiography to testimony to political theory, translating from events on the Malecón (the long waterside promenade in Havana dubbed “Cuba’s great sofa”) to the masculine histories of the Cuban state and back again. It is also – for those seduced by such things – a book beautiful to look at, and to hold (which is a way of saying that you should buy a hard copy). It is a book about evasion, repression and muddled motives, but is itself a model of generosity and clarity.

The central figure throughout is the ‘jinetera’, superficially close to the idea of a ‘prostitute’ but evidently much more ambiguous in definition and shifting in practice. As Megan explains, the term ‘jinetera’ and the general practice ‘jineterismo’ are plays on ‘jockeying’, meaning to manoeuvre for advantage and also to have sex, both connotations clearly playful, if also risky (see the previous posts in the forum for more discussion on the meaning and forms of jineterismo).[2] It is with a curiosity about jineterismo that Megan starts. But where we end up is inside an indispensable guide to the ‘sexual-affective economy’, a bold innovation in disciplinary writing, and a testament to the difference gender analysis makes in studying the global political.

From Cuba With Love does what a certain kind of post-structural feminist IR does best, dissecting the identities created by, and in, a concrete historical system. Not the narrow ‘identity politics’ critics abhor, but identity as the fullness of lived experience shot through with power, subjectivities which are at once deeply personal (love, hope, desire, sex) and interwoven with the most brute forms of political violence (the state, the prison camp, the rehabilitation centre, the police system, imperialism and resistance, exclusion and poverty). It is a study that is undeniably ‘global’ in its scope, even about inter-national relations in a rather precise sense, given how often the admixture of sex and money circles the desires of the (usually) western male for a ‘local’ rendezvous, and how implicated notions of race, nation, difference, rivalry, trade, progress, savagery, miscegenation, and geopolitical virility are in that. A kind of diplomacy, even. This is an encounter with ‘the Other’, and a negotiation of the foreign, in its most visceral possible form. Or, as one key informant more bluntly puts it:

It’s different if one goes to bed with a foreigner, or a mountain of foreigners…Do we have to carry such chauvinistic patriotism with us in our pussies too? Is it obligatory to make use of a mambí dick? Or are they trying to avoid alienating penetrations?

Yet From Cuba With Love is not just a great success on those terms. It is also in many ways the stand-out example of ‘narrative IR’, that vague but increasingly popular sub-field (or is it a method?) devoted to exploring world politics from the situated perspective of someone experiencing it (that someone usually being the researcher themselves). Continue reading

The ‘Affectual’ Jockeys of Havana

The fourth post in our mini-forum on Megan’s From Cuba With Love.

Megan Daigle’s from Cuba with Love: sex and money in the 21st century is a crisply written treatise on what is often narrowly understood as “sex work” and “sex tourism” in contemporary Cuba. Set largely against the backdrop of the Malecon in Havana, Megan explores the complex practice of jineterismo in From Cuba. Jineterismo or “jockeying” is “the practice of pursuing relationships with foreign tourists” that has resulted in the creation of what Megan calls a “sexual-affective economy” in Cuba in the post Cold War era, specifically in light of the US economic embargo.

Megan’s interactions with the young Cubans she interviews and speaks with at length, highlight the abject failure of labels such as “sex work” and “prostitution” to capture the myriad and variegated bonds that these Cubans form with their Western benefactors, or more aptly, partners. She grants them agency as actors and decision-makers who get into relationships with foreign men for reasons that include and transcend material gain.

With equal sensitivity and nuance, Megan also maps the raced, gendered and classed dimensions of the reactions which reactions? these relationships engender, focusing in particular on the multiple levels at which these young women are subject to violence; most notably meted out by the socialist state and its affiliated institutions. The state’s disparaging dismissal of this economy of love, if you like, is both predictable and curious. On the one hand, jineterismo is construed as a consumerist impulse that must be crushed in order for the citizens of Cuba to remain true to the ideals of the revolution. On the other, the relative sexual freedom young Cubans enjoy is something of an anomaly that is owed at least partially, to the propagation of women’s rights through the (admittedly problematic) Federation of Cuban Women (FMC).

From Cuba with Love: Sex and Money in the 21st Century

Five years ago, I spent six months living and working in Cuba – a fact that, in casual conversation, generally provokes expressions of envy and eye rolling about mojitos, salsa music, and academics who don’t really do any work. Cuba is as much a fantasy as a real place. It is totally invested with the romantic and ideological dreams of wildly disparate constituencies: armchair socialists and campus lefties, right-wing US politicians and Cuban émigrés, cocktail-swilling package holiday tourists, and adventure-seeking backpackers, amongst others. Cuba is a steamy and exotic Caribbean island, with rumba dancing and free-flowing rum. Cuba is a repressive and secretive regime. Cuba is a test workshop for socialist ambitions the world over. Cuba is a fantasy.

It was ideas like these about Cuba, Cuban politics, and Cuban people that drew me there in the first place, and the resulting book – built on those months of ethnographic research and on the doctoral dissertation that followed – has recently been released under the title From Cuba with Love: Sex and Money in the Twenty-First Century (University of California Press 2015). Rahul, Nivi, guest poster Dunja, and Pablo will be commenting on it over the next few days, followed by a rejoinder from yours truly.

More Notes for Discerning Travellers

A little while ago I wrote a blog, Notes on Europe and Europeans for the Discerning Traveller. It was a fictional travel guide, but with all points speaking to historical realities.

What is it about a certain “European” sensibility? Not all people who live in European countries have it, of course, but this sensibility seems to define in the main what it means to be essentially “European”). I want to ask: what is it about a sensibility that can never, ever, look at itself, for itself, and in relation to what it does to others?

We all know that the European enlightenment was supposed to be built upon the pillars of self-reflection and accountability in thought and politics. It is funny, then, that the “European” so rarely seemed to be able to hold him/herself to reflexive account especially over European colonial pasts.

It continues.

I swear, if I believed in such a cosmology called “Modernity” I’d be calling the “European” a backward, traditional native ensconced in his/her own culture, taking his/her particulars for mystical universals, and unable to look at him/herself in the mirror to start the process of socialization and “childhood development”.

But I don’t believe. So I’ll just have to call this sensibility by more mundane descriptions, such as un-reflexive, un-accountable, un-relational.

Example (twitter response to my Travel Notes blog): Continue reading