I am extremely grateful to Elin, Clara and Katie for writing such thoughtful and thought-provoking engagements with Societies Under Siege, and to Joe Hoover for kindly organising this forum. It is not easy to set aside the time during a busy teaching term. Here is my reply!

Policy Relevance

Mind the Gap: Evaluating the Success of Sanctions

This is the third in a series of posts on Lee Jones’ Societies Under Siege: Exploring How International Economic Sanctions (Do Not) Work. We are delighted to welcome Dr Clara Portela, she is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Singapore Management University. She is the author of the monograph European Union Sanctions and Foreign Policy, for which she received the 2011 THESEUS Award for Promising Research on European Integration. She recently participated in the High Level Review of United Nations sanctions, in the EUISS Task Force on Targeted Sanctions and has consulted for the European Parliament on several occasions.

This is the third in a series of posts on Lee Jones’ Societies Under Siege: Exploring How International Economic Sanctions (Do Not) Work. We are delighted to welcome Dr Clara Portela, she is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Singapore Management University. She is the author of the monograph European Union Sanctions and Foreign Policy, for which she received the 2011 THESEUS Award for Promising Research on European Integration. She recently participated in the High Level Review of United Nations sanctions, in the EUISS Task Force on Targeted Sanctions and has consulted for the European Parliament on several occasions.

A further response will follow from Katie Attwell, followed by a response from Lee. You can find Lee’s original post here and Elin Hellquist’s here.

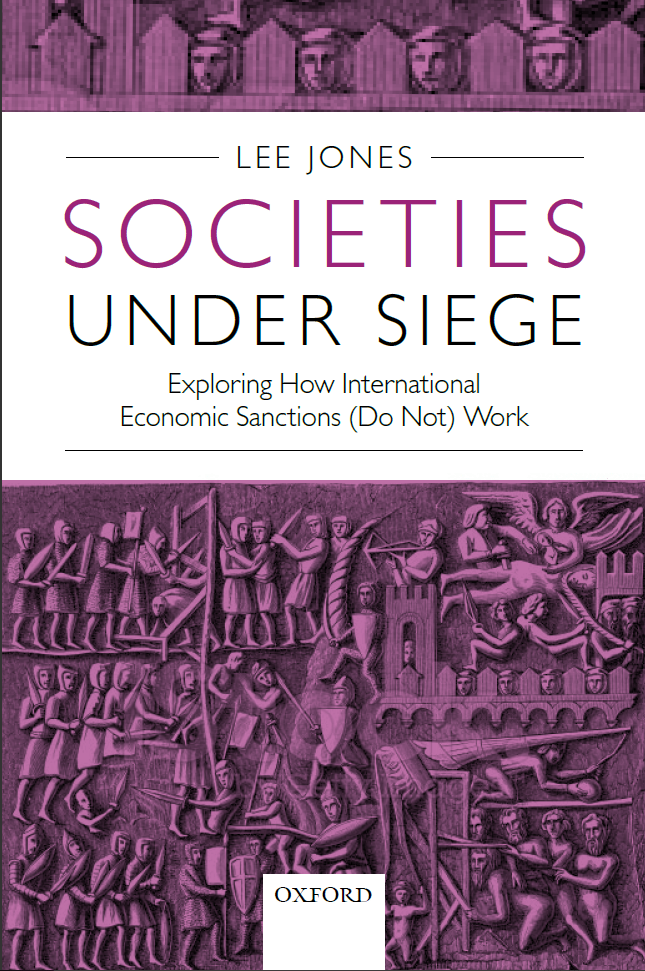

The volume undoubtedly makes a key contribution to the field – indeed, one that was sorely needed: an evaluation of how sanctions interact with the economic and political dynamics in the target society, and more specifically, how they affect domestic power relations. This agenda is not entirely new in sanctions scholarship. It had been wisely identified by Jonathan Kirshner in a famous article as far back as in 1997. However, having pointed to the need to ascertain how sanctions affect the internal balance of power between ruling elites and political opposition, and the incentives and disincentives they faced, this analytical challenge had not been taken up by himself or any other scholar so far. The book also contributes to a highly promising if still embryonic literature: that of coping strategies by the targets, briefly explored in works by Hurd or Adler-Nissen.

Departing from the idea that whether sanctions can work can only be determined by close study of the target society and estimating the economic damage required to shift conflict dynamics in a progressive direction, the study proposes a novel analytical framework: Social Conflict Analysis. The volume concludes that socio-political dynamics in the target society overwhelmingly determine the outcomes of sanctions episodes: “Where a society has multiple clusters of authority, resources, and power rather than a single group enjoying a monopoly, and where key groups enjoy relative autonomy from state power and the capacity for collective action, sanctions may stand some chance of changing domestic political trajectories. In the absence of these conditions, their leverage will be extremely limited” (p.182).

Societies Under Siege: Exploring How International Economic Sanctions (Do Not) Work

This is the first in a series of posts on Lee Jones’ Societies Under Siege: Exploring How International Economic Sanctions (Do Not) Work. Responses will follow from guest authors Elin Hellquist, Clara Portela and Katie Attwell over the next few days.

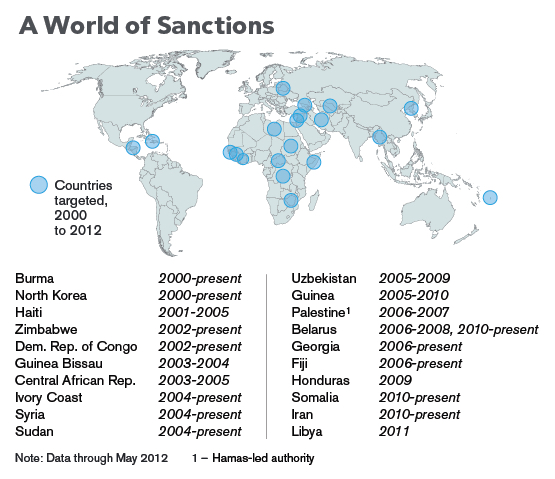

It doesn’t seem to matter what the international crisis is: be it an inter-state war (Russia-Ukraine), civil strife (Syria), gross violations of human rights (Israel), or violent non-state actors on the rampage (ISIS, al-Qaeda), the ‘answer’ from governments and civil society always seems to be the same: impose economic sanctions. In the mid-20th century, only five countries were targeted by sanctions; by 2000, the number had increased tenfold. Once an obscure, rarely used and widely dismissed form of statecraft, sanctions are now clearly central to the exercise of power in international relations – particularly when dominant powers are reluctant to put ‘boots on the ground’.

My new book, Societies Under Siege: Exploring How International Economic Sanctions (Do Not) Work, is the first comparative effort to explore how these sanctions ‘work’ in practice – on the ground, in target states. This post introduces the book and the forum that will follow.

Twilight of the Journal Vampire Squid

This was in someone’s open access slide show someplace, but the name, and therefore the credit, escapes me.

I have a piece up at e-IR today returning to the question of open access. It is partly an introduction to the issues, partly a manifesto on why academics should take the digital commons more seriously. But it is mainly intended as a provocation for the discipline (proto-discipline, non-discipline, borg-discipline, what you will) of IR, and a challenge to the in my view excessive resistance to open access that characterises its upper echelons. To wit:

What is IR’s contribution to the open access movement? Almost nothing, arguable less than nothing. There is no IR equivalent of ArXiV – the hugely successful online repository favoured by physicists and mathematicians. Nor of PLOS – the gigantic open access mega-journal suite favoured by hard scientists, which sustains itself on low relative processing charges. Nor of Cultural Anthropology – a learned society journal gone fully open access. No experiment like the Open Library of the Humanities – a new platform-cum-mega-journal funded by a conglomerate of libraries. No appetite for something like Sociological Science – an open access journal with quick review times and low, means-tested article publishing costs. There are a handful of open access IR journals, like Ethics & Global Politics (not to be confused with Ethics & International Affairs), the Journal of Critical Globalisation Studies, and the Journal of Narrative Politics, run largely on goodwill, but they are sadly lacking a disciplinary presence. Publishing in them will not make a career, and is unlikely to impress hiring committees which have an eye to bankrupt measures of quality like the journal impact factor.

Worse still, the discipline of IR has missed opportunities to make itself more open and relevant, all the while fretting over its introversion and lack of relevance. Some of our responses to the open access movement have been sadly conservative and dismissive. New journals like the European Journal of International Security and the Journal of Global Security Studies are run on the standard closed model. Neither the leadership of the British International Studies Association nor the International Studies Association have followed the innovations carved out by colleagues in anthropology, sociology or STEM subjects. And young journals that position themselves as disrupting orthodoxy (such as Critical Studies on Security) have nevertheless emerged under the imprint of familiar publishing houses. While Editorial Boards in other disciplines are considering resignation and boycott to force change on the system, IR scholars are joining an ever-growing list of titles that promote business as usual. Closed journal publishing has become common sense: unquestioned despite its manifest failings.

The Dissonance Of Things #4: Leftist Foreign Policy After Corbyn

The fourth of our monthly podcasts, turning our attention with ever greater political precision to Corbynmania, Jacorbynism, #JezWeCan, or however you prefer to characterise the arrival of Jeremy Corbyn as Leader of the UK Labour Party. Since before his victory, Corbyn has been stalked by, and occasionally celebrated for, his views on international politics, from the crisis in Ukraine and associated Great Power rivalries to his views on Hamas and from the (non-)renewal of Trident to the UK’s future role in NATO. David Cameron, for one, has attempted to securitise Corbyn, repeatedly arguing that “the Labour Party is now a threat to our national security, our economic security and your family’s security”.

And so we ask: what is a leftist foreign policy? Is such a thing even possible? Should the left, in whatever form, be seeking to capture, remake or resist foreign policy? What do the wishlist strands of a left foreign policy look like? Lee, Meera and I are herded into some kind of order by Kerem, and joined by Chris Emery of the University of Plymouth. author of US Policy in Iran: The Cold War Dynamics of Engagement and Strategic Alliance 1978-81 and this post on the history of covert action in Iran.

As ever, consume, cogitate, argue, and share, share, share. Past and future casts are available on soundcloud.

Further resources, including articles discussed in the podcast:

- Lee, ‘Why Syriza Failed’

- John Mearsheimer, ‘Why the Ukraine Crisis is the West’s Fault’, Foreign Affairs

- Peter Oborne, ‘Corbyn will confront a bankrupt foreign policy’, Middle East Eye

- ‘Jeremy Corbyn’s Contradictory Foreign Policy’, Hands Off The People Of Iran

- Ralph Miliband, Parliamentary Socialism: A Study in the Politics of Labour (1961/1972)

The Corbyn After-Effect

Win he did. And how. Although the petty vindictiveness of the #LabourPurge was real, it wasn’t enough to materially affect the result, and has arguably strengthened Jeremy Corbyn’s mandate. Even as dodgy expulsions and dodgier retentions sour the taste, nobody can claim that the Labour elite were too lax in their efforts to hobble him. For those who have felt blackmailed and maligned by New Labour and its outriders this past decade or two, the moment of joyful disbelief is to be relished. A social democrat as leader of the Labour Party! What a notion. Negative solidarity is giving way to a new structure of feeling, not just resisting but asserting positively the horizon of a more egalitarian, less parochial politics. It was fitting that Corbyn’s ascent took place on the same day as the major London march in defence of refugees, and that he moved amongst us.

The euphoria won’t last, is indeed already muted, tempting us to get our disappointment in early. Continue reading

The Corbyn Effect

In the last days, the Labour mainstream has not so much fallen as fully leapt into a fit of apoplexy. The cause an opinion poll – by no means solid, by no means a guarantee of future stock value – placing Jeremy Corbyn as the likely winner of the party’s leadership contest. Labour MPs, some now publicly flagellating themselves, nominated Corbyn for a ‘balanced debate’, but apparently couldn’t countenance that it might actually lead anyone to, you know, debate. Corbyn’s moment of popularity is thus sketched as, among other things, “the emotional spasm…an apocalyptic tendency”. John McTernan – a prime mover in the utter implosion of Labour in Scotland – was invited to hold forth on national TV as an oracle nevertheless, where he showed off his great talent in persuasion by calling Labour supporters “morons”. John Rentoul, that other great passé hack, thought recognising the left-wing appeal of the SNP as a factor in Labour’s defeat was like believing in space lizard conspiracy theories.

There was an equal portion of patronising bullshit to go with the name-calling. “Do some research” before you dare to a preference, chided Anne Perkins. Don’t be a “petulant child”, admonished Chuka Umunna. Sunny Hundal came at logic with customary cack-handedness, transforming the clear articulation of principles into a pathology. These are some of the same people who bemoan the detachment of politicians from real people, the decline in party membership, and so on, only to rise up as vengeful furies when a candidate dares to stir energies. All down to an unsavoury populism, natch. This, says Helen Lewis, is ‘purity leftism’, nothing like the necessary compromises of opposition, where you have to be bold enough to endorse 2% defence spending (something “the public” indeed likes, although hardly top of their polled priorities). Blair, of course, can only relate in the terms of triangulation, regurgitating the 1990s whilst pretending to the terrain of the future.

It doesn’t matter that Corbyn’s record is one of social democracy (remember that?). It doesn’t matter that there are trends in his favour. It doesn’t matter that his economic policies are comparatively bold and redistributive. It doesn’t even matter that many of Corbyn’s policies are popular. One line of Blair’s intervention was widely cited: “I wouldn’t want to win on an old fashioned leftist platform”. Few completed the quote: “…even if it was the route to victory“. This is not political argument, nor even Machiavellian electoral planning, but the tantrum-jitters of the self-appointed aristocracy. Having passed out lectures on loyalty and collective responsibility on Monday during the second reading of the Welfare Bill, the dauphins were by Thursday pre-declaring a coup should Corbyn win and practically spitting on their own activists besides. They saw no contradiction. Labour’s experts advocate not political communication but political manipulation, impersonating the enemy to take their place in our collective consciousness.

And so it will go on if any of the appeasement candidates win. Continue reading

Can Metrics Be Used Responsibly? Why Structural Conditions Push Against This

Today, the long-awaited ‘Metric Tide’ report from the Independent Review of the Role of Metrics in Research Assessment and Management was published, along with appendices detailing its literature review and correlation studies. The main take-away is: IF you’re going to use metrics, you should use them responsibly (NB NOT: You should use metrics and use them responsibly). The findings and ethos are covered in the Times Higher and summarised in Nature by the Review Chair James Wilsdon, and further comments from Stephen Curry (Review team) and Steven Hill (HEFCE) are published. I highly recommend this response to the findings by David Colquhoun. You can also follow #HEFCEMetrics on Twitter for more snippets of the day. Comments by Cambridge lab head Professor Ottoline Leyser were a particular highlight.

I was asked to give a response to the report at today’s launch event, following up on the significance of mine and Pablo’s widely endorsed submission to the review. I am told that the event was recorded by video and audio so I will add links to that when they show up. But before then, a short summary record of the main points I made: Continue reading

The Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative and Its Critics

I have a piece out in the latest International Affairs on the UK government’s Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative (PSVI), better recognised as that thing William Hague did with Angelina Jolie(-Pitt) when he was still Foreign Secretary. As well as an important project in its own right, the Initiative might be read as signalling a new front in ethical foreign policy, and another success story in feminist activism around sexual violence (alongside the rise of ‘governance feminism’ and what have been called ‘femocrats’ in the UN and elsewhere). The role of the UK as a diplomatic and political presence becomes more important still against the background of rising attention to gender in global policy discourse in recent decades (conventionally referred to as the ‘Women, Peace and Security’, or WPS, agenda). Alternatively, the PSVI might be understood as a cause without demonstrable success, already fading from the scene along with Hague, its main advocate. And from either a conventionally Realist or a more radical activist perspective, the chances of a Foreign Office-led policy initiative making any feminist ground would seem slim.

Against this background, and building on a few years of following the Initiative’s progress, I stake out a preliminary analysis of three planks of the PSVI’s work. First, its wholesome embrace of ‘weapon of war’ thesis. Second, the great emphasis on ending impunity as the most effective means to reduce atrocity. And third, the repeated foregrounding of men and boys as ignored victims of sexual and gender-based violence. The headline conclusion is that, despite its promise, the initiative has thus far achieved little on its own technical terms, and its underlying approach to gender violence in conflict is in important senses limited. The conceptual bases of this relative failure lie in an unduly simplistic account of where and why such violence happens and an inability to reckon with the lack of evidence for strong deterrence effects or the significant resource challenges involved in supporting local and national justice programmes. By contrast, the PSVI stands as an important moment in the opening out of policy understandings of gender violence, although there nevertheless remain important ambiguities over ‘gender neutrality’ in practice, and therefore a likelihood of disputes over resources.

The arrival of the Hague-Jolie Initiative onto the WPS scene was unexpected. The Conservative manifesto for the 2010 general election made no mention of wartime sexual atrocity, and was utterly conventional in its references to human rights. UK support for Security Council resolutions aside, activities on sexual violence have historically come from the Department for International Development (DFID), and with the exception of the attention generated during the London summit, the UK government has not made much of the initiative in its public relations since. The PSVI is thus heavily identified with William Hague personally, and can be traced to his epiphany over the role of genocidal rape in Bosnia. Hague, who is also the biographer of William Wilberforce, has framed war rape as similar to slavery in its immorality and argued for the role of the UK as an abolitionist force, repurposing standard diplomatic practice to progressive ends. This is to seek nothing less, in his words, than “the eradication of rape as a weapon of war, through a global campaign to end impunity for perpetrators, to deter and prevent sexual violence, to support and recognise survivors, and to change global attitudes that fuel these crimes”.