UPDATE (31 May): Crooked Timber have picked up the issue too. And MacShane has replied (in the comments at openDemocracy). His riposte is aptly characterised by Michael Otsuka as a “simulacrum of a genuine apology”. In short, having called into question the intellectual faculties of an LSE Professor and described her views as poisonous drivel (not that they were her views you’ll remember), MacShane now claims he meant no offence. Having taken words out of context, mis-attributed intentions and views to Phillips and not considered the conditions in which the question was posed, MacShane now complains that he is taken out of context, that the complainants don’t understand his views and that they haven’t considered the conditions in which his question was posed. Yes, really. Readers can surely decide for themselves, although we should not think too highly of a rear-guard ‘apology’ which begins “Gosh, well it makes a change from the BNP and Europhobes having a go” and ends “I just wish I was 100 per cent certain that…there is not a scintilla of concern out there in academistan that rather than posit an either/or argument a stand might be taken”. Yes, academistan. And in case you’re puzzled by what the ‘scintilla of concern’ refers to, it’s not the academic freedom issues raised by the Association for Political Thought and it’s not about elected Members trawling reading lists for cod-incriminating questions with which to verbally bash named academics. Instead what is meant is that by protesting his error, we supposedly signal that we’re not that bothered about the wrongs of sex trafficking and prostitution. What to say about such logic? Concerned members of the Association for Political Thought can apparently add their names to the statement by contacting Elizabeth Frazer (Oxford): elizabeth.frazer@new.ox.ac.uk.

UPDATE (30 May): Happy to see that this issue has been picked up by Liberal Conspiracy, openDemocracy, Feminist Philosophers and others. There’s now a statement with signatures from members of the Association for Political Thought condemning Denis MacShane in appropriately harsh terms (although I think it’s a tad hard on Fiona Mactaggart who, after all, was responding off the cuff to an unsolicited intervention, and did somewhat trim her comments by talking about ‘sufficient challenge’ to all views). People certainly keep following links here, more than a week on. I’m not aware of any response from MacShane himself, although I know from several readers that his office has been contacted about this matter. He certainly hasn’t tweeted about it. Perhaps these new developments might convince him of the need to correct some of his own views.

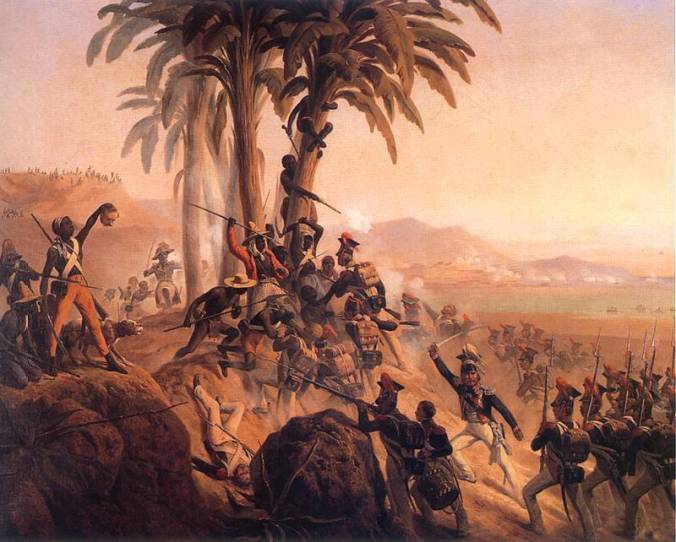

LSE-bashing is certainly in vogue. Following the travesties of GaddafiGate, some are eager to find further fault. Enter the Rt Hon Dr Denis MacShane MP (PhD in International Economics, Birkbeck, 1990). During a Commons debate earlier this week on human trafficking, he responded to the citing of an LSE report on the treatment of victims thusly:

Mr MacShane: My hon. Friend mentioned the London School of Economics. Is she aware of its feminist political theory course, taught by Professor Anne Phillips? In week 8 of the course, students study prostitution. The briefing says:

“If we consider it legitimate for women to hire themselves out as low-paid and often badly treated cleaners, why is it not also legitimate for them to hire themselves out as prostitutes?”

If a professor at the London School of Economics cannot make the distinction between a cleaning woman and a prostituted woman, we are filling the minds of our young students with the most poisonous drivel.

Fiona Mactaggart: I share my right hon. Friend’s view about those attitudes. I hope that the LSE provides sufficient contest to Professor Phillips’s frankly nauseating views on that issue.

Quentin Letts of The Daily Mail, a patronising faux-wit at the best of times, has now picked up the scent and is ready to draw the appropriate conclusions:

Legitimate academic inquiry? Or evidence of drift towards the position of seeing prostitutes as ‘sex workers’? (They’ll want membership of the British Chambers of Commerce next.)…Phillips, a past associate of David Miliband, bores for Britain on the global feminism circuit. I am told she has the hide of an elk. But why, at a time of university cuts, do we need a Gender Institute?

And so ignorance compounds ignorance. MacShane, and by extension Letts, deal in both misrepresentation and in condescending intellectual proscription.

Continue reading →