This post is part of a syposium on Meera Sabaratnam’s Decolonising Intervention. Meera’s original post, with links to the other contributions, is here. If tweeting, please use #DecolonisingIntervention!

Postcolonial/ decolonial research seems to be entering into what might be called a “second generation”, moving past early, de-constructive critiques of the IR discipline as racist and colonial, and into showing the “value added” of a decolonial approach in studying concrete problems in international politics. Decolonising Intervention is an important contribution to this effort.

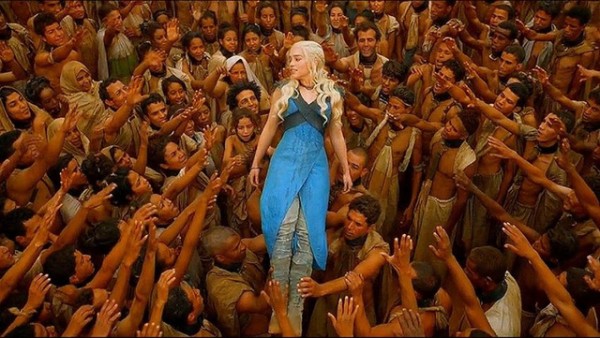

Sabaratnam’s basic argument is quite straightforward. Like many critical scholars of intervention, she documents multiple failures of Western statebuilding interventions (SBIs) to resolve the problems they (allegedly) seek to address. Unlike them, however, she attributes these recurrent failures – persistent, despite widespread acknowledgement, even among interveners, and within a gargantuan “lessons learned” literature – to the “colonial” structure of global politics. Put simply: Western donors feel superior to the targets of intervention, and so simply cannot learn from their mistakes. They are obsessed with their own starring role (protagonismo), making them congenitally incapable of deferring to their targets’ concerns, ideas, knowledge or demands. They garner the lion’s share of donor funds, scarcely caring if interventions work or not, implicitly seeing targets’ time and resources as “disposable”. Dependent recipients have little choice but to engage, or lose what resources are offered.

ity of Essex. He is co-editor, with

ity of Essex. He is co-editor, with