Mother, stepmother, perfidious Albion—whatever metaphor one prefers to employ, Britain has always been important to Canada. But what is Canada to Britain? It depends on whom you ask.

This post originally appeared on Open Canada.

Mother, stepmother, perfidious Albion—whatever metaphor one prefers to employ, Britain has always been important to Canada. But what is Canada to Britain? It depends on whom you ask.

This post originally appeared on Open Canada.

This is the third in a series of posts on Lee Jones’ Societies Under Siege: Exploring How International Economic Sanctions (Do Not) Work. We are delighted to welcome Dr Clara Portela, she is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Singapore Management University. She is the author of the monograph European Union Sanctions and Foreign Policy, for which she received the 2011 THESEUS Award for Promising Research on European Integration. She recently participated in the High Level Review of United Nations sanctions, in the EUISS Task Force on Targeted Sanctions and has consulted for the European Parliament on several occasions.

This is the third in a series of posts on Lee Jones’ Societies Under Siege: Exploring How International Economic Sanctions (Do Not) Work. We are delighted to welcome Dr Clara Portela, she is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Singapore Management University. She is the author of the monograph European Union Sanctions and Foreign Policy, for which she received the 2011 THESEUS Award for Promising Research on European Integration. She recently participated in the High Level Review of United Nations sanctions, in the EUISS Task Force on Targeted Sanctions and has consulted for the European Parliament on several occasions.

A further response will follow from Katie Attwell, followed by a response from Lee. You can find Lee’s original post here and Elin Hellquist’s here.

The volume undoubtedly makes a key contribution to the field – indeed, one that was sorely needed: an evaluation of how sanctions interact with the economic and political dynamics in the target society, and more specifically, how they affect domestic power relations. This agenda is not entirely new in sanctions scholarship. It had been wisely identified by Jonathan Kirshner in a famous article as far back as in 1997. However, having pointed to the need to ascertain how sanctions affect the internal balance of power between ruling elites and political opposition, and the incentives and disincentives they faced, this analytical challenge had not been taken up by himself or any other scholar so far. The book also contributes to a highly promising if still embryonic literature: that of coping strategies by the targets, briefly explored in works by Hurd or Adler-Nissen.

Departing from the idea that whether sanctions can work can only be determined by close study of the target society and estimating the economic damage required to shift conflict dynamics in a progressive direction, the study proposes a novel analytical framework: Social Conflict Analysis. The volume concludes that socio-political dynamics in the target society overwhelmingly determine the outcomes of sanctions episodes: “Where a society has multiple clusters of authority, resources, and power rather than a single group enjoying a monopoly, and where key groups enjoy relative autonomy from state power and the capacity for collective action, sanctions may stand some chance of changing domestic political trajectories. In the absence of these conditions, their leverage will be extremely limited” (p.182).

The following was originally posted on The Current Moment, a blog exploring contemporary politics and political economy in the West. Especially for those concerned with the Eurozone crisis and the impending British referendum on European Union membership, it is a must read!

* * *

Recent events in Greece have baffled many observers. At the end of June, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras walked out of talks with Greece’s creditors, calling a snap referendum on their proposals. It appeared to be crunch time. Tspiras denounced the EU’s ‘blackmail-ultimatum’, urging ‘the Hellenic people’ to defend their ‘sovereignty’ and ‘democracy’, while EU figures warned a ‘no’ vote would mean Greece leaving the Euro. Yet, even during the referendum campaign, while ostensibly pushing for a ‘no’ vote, Tsipras offered to accept the EU’s terms with but a few minor tweaks. And no sooner had the Greek people apparently rejected EU-enforced austerity than their government swiftly agreed to pursue harsher austerity measures than they had just rejected, merely in exchange for more negotiations on debt relief. This bizarre sequence of events can only be understood as a colossal political failure by Syriza. Elected in January to end austerity, they will now preside over more privatisation, welfare cuts and tax hikes.

How can we explain this failure? I argue three factors were key. First, the terrible ‘good Euro’ strategy pursued by Syriza, the weakness of which should have been apparent from the outset. The second factor, which shaped the first, is the overwhelmingly pro-EU sentiment among Greek citizens and elites, which created a strong barrier to ‘Grexit’ in the absence of political leadership towards independence. Third, the failure of the pro-Grexit left, including within Syriza, to win Syriza and the public over to a pro-Grexit position.

Southeast Asia’s recent Rohingya refugee crisis, and the parallel and still-unfolding horrors in the Mediterranean, are stark and tragic reminders of how the nature of international security has changed in recent decades. Traditionally, security involved building military strength to deter or repel attacks by other states. Today, beyond a tiny handful of ‘flashpoints’, so-called ‘non-traditional’ security issues dominate: irregular migration, drug trafficking, terrorism, piracy, pandemic disease, environmental degradation, transnational organised crime and cybersecurity – to name but a few. How are states and international organisations dealing with these challenges, and what does this tell us about global politics today?

The latest “boat people” crisis

Following the Radical Left Assembly #2 last weekend, Nivi and Kerem caught up with Luke Cooper to discuss the implications of the Conservative Party majority for British politics. What does the election result tell us about the political composition of Britain? What is the significance of the Tory pledge for a referendum on the EU? And what future is there for a politics of the Left?

Following Part I, and in advance of Part III.

The court is political

The smartass response goes something likes this: “Of course it’s political; what’s not political? Haven’t you read the ICTY’s website? It says clearly that the tribunal was established for explicitly political reasons, too, by the UNSC, which is political by definition.” But the smartass response is a rude interruption. The above assertive prefaces monologue, not dialogue. The monologue is a story about world politics as a dog-eat-dog contest in which the strong always devour the weak with a focus on the origins of the ICTY. “Of course an international judicial institution cannot be created on the basis of an UNSC resolution alone. Of course Chapter VII of the UN Charter does not specify the conditions under which war crimes tribunals can be set up. Of course the ICTY quickly discovered that it could not bother with the question of own legality. But when have great powers ever cared about law and institutions? Might makes right, right? The ICTY is based on the consent of states – big states, not our banana republics.”

This story varies in terms of breadth and depth, but its modal conclusion is that the tribunal cannot represent anything but “victor’s justice” and/or Western and specifically American oppression of those living on the periphery. As for the motive, the supposedly aggressive prosecution of Bosno-Serbo-Croat baddies practiced by the ICTY is a function of the desire for retribution for every case of ex-Yu insolence in recent history, starting with the Trieste crisis of 1945. As discipline and punishment at once, trials are also meant to serve as a warning to the rest of the peripheral and semi-peripheral world. This type of theorizing could be described as a cross between pop-realism and pop-Marxism with a whiff of the crudest forms of pop-anti-Americanism and some other, far less respectable prejudices. While it is not exactly a closed loop, for every new newstory indexing Western and specifically American double standards and double visions in international law, the theory gains strength. Who in the former Yugoslavia doesn’t have an informed opinion on the “Hague Invasion Act”?

The two accounts of the origins of the ICTY that I have on my shelf make something of an opposite case. Pierre Hazan’s book, subtitled ‘The True Story Behind the ICTY’, suggests that the weak (international justice activists) outfoxed the strong (realist diplomats and state-centric lawyers) and, against all odds, managed to turn the tribunal into such a revolutionary achievement (more on this below). Hazan is no theorist of norms and transnational advocacy networks, but there are more than a few parallels with this literature. The second account is Rachel Kerr’s 2004 book, which begins and ends with the thorny issue of “politicization,” including the issue of “prosecutorial discretion” as its special subset. Kerr has the ICTY walking on a tightrope. Sidle up too closely to justice, and you alienate those who rule the world; let politics in, even to manipulate it for judicial ends, and you lose credibility. While infinitely more nuanced than Hazan’s, Kerr’s framework for analyzing politics (it, too, chimes with 1990s IR theory, namely the “bringing international law back in” literature) follows the same binary – let me personify it a little as a contest between “realists” versus “legalists” – and it reaches the same conclusion. And judging by both the quotidian operation of the court as well as its key decisions up to 2002-3, Kerr finds, “legalists” had the upper hand.

The two accounts of the origins of the ICTY that I have on my shelf make something of an opposite case. Pierre Hazan’s book, subtitled ‘The True Story Behind the ICTY’, suggests that the weak (international justice activists) outfoxed the strong (realist diplomats and state-centric lawyers) and, against all odds, managed to turn the tribunal into such a revolutionary achievement (more on this below). Hazan is no theorist of norms and transnational advocacy networks, but there are more than a few parallels with this literature. The second account is Rachel Kerr’s 2004 book, which begins and ends with the thorny issue of “politicization,” including the issue of “prosecutorial discretion” as its special subset. Kerr has the ICTY walking on a tightrope. Sidle up too closely to justice, and you alienate those who rule the world; let politics in, even to manipulate it for judicial ends, and you lose credibility. While infinitely more nuanced than Hazan’s, Kerr’s framework for analyzing politics (it, too, chimes with 1990s IR theory, namely the “bringing international law back in” literature) follows the same binary – let me personify it a little as a contest between “realists” versus “legalists” – and it reaches the same conclusion. And judging by both the quotidian operation of the court as well as its key decisions up to 2002-3, Kerr finds, “legalists” had the upper hand.

I am not sure what stock-taking exercises based on the realist vs. legalist framework look like today (again, this post is my attempt to reconnect with the literature I stopped following years ago), but what struck me in my conversations is how adamant my interlocutors were in rejecting even the most carefully drawn legalist claims. It’s simple, the typical response goes, the ICTY is subject to constant political pressures and it shouldn’t be surprising to see so much judicial malpractice. Lest one is keen to dismiss this as “typical” ex-communist (and transitionalist) disdain for the notion that law serves to ensure that valuable social goods are distributed in ways that protect equal respect for everyone, note that some of the most critical arguments about the “hopelessly political court” are drawn from the texts left behind by bona fide ICTY insiders like Antonio Cassese (he of those great international law textbooks), Gabrielle Kirk McDonald, Louise Arbour, Graham Blewitt, Carla Del Ponte, Serge Brammerz, and Florence Hartmann (more below). Anyone can cherry-pick a few memorable lines from a few memoirs and journalistic accounts (Hartmann, if I recall correctly: “the ICTY was formed so that war criminals could negotiate on the level of their innocence”), but what I find interesting is that these types of arguments have gained more and more adherents over the years.

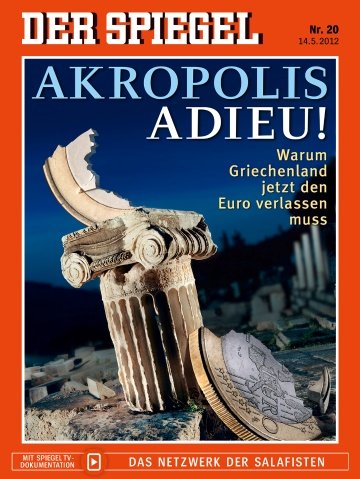

As the inevitable Greek exit from the eurozone seemingly approaches, it’s worth comparing current statements about Greece to how the financial press and regulators considered Lehman Brothers the week before its collapse set the global markets into panic mode. (See below for a selection of illuminating comments from officials about Lehman Brothers pre-collapse and about Greece pre-exit.) Reading these misplaced predictions, one thing becomes clear: the contemporary financial system is far too complex and opaque for anyone to determine the precise consequences of a Greek exit. Add into that the unpredictable nature of crisis politics (e.g. today sees rumors of Greek governing coalitions flying all over the place), and one has a system that quickly surpasses our capacities for forecasting. In this regard it’s interesting to read reports about the current Greek exit fears versus the reports in February when it also looked like Greece might leave (prior to the second of ECB’s long-term refinancing operations (LTROs) that managed to calm markets for a short while). In the earlier reports many commentators considered that French and German banks had largely separated themselves from Greek exposure, while the initial LTRO had purportedly given the financial system the flexibility it needed to survive any temporary disruption. Intriguingly, today’s fears about Greece, after the failure of the LTROs to significantly improve the situation and combined with fears over Spain’s banking system, are much more apocalyptic than in February.

The unfortunate truth is that while a Greek exit will be devastating to the Greek people (of this everyone is confident), it is still a better option than the continued austerity regime. Even the most optimistic IMF estimates of Greece’s economy under the austerity regime only see them returning to 120% debt-to-GDP ratio by 2020 – i.e. the same level that so worries commentators about Italy today. What is being asked of Greece is a state of permanent austerity and permanent social chaos.

September 9, 2008 – http://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/10/business/10place.html?pagewanted=all

Unlike Bear Stearns, which effectively collapsed when customers fled for the exits and the firm could not finance itself, Lehman Brothers has more sources of long-term financing and like other broker-dealers, access to emergency financing from the Federal Reserve. Mr. Fuld said that the existence of that lending facility should take any question of Lehman facing a liquidity crisis “off the table.

September 12, 2008 – http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/b3506214-80d5-11dd-82dd-000077b07658.html#axzz1mXeJ33ET

While the crisis at Bear stunned the markets, other financial institutions have had six months to prepare for the possible failure of Lehman. In the Bear crisis, the risks were extreme in part because they were unknown and unmanaged. The New York Fed has conducted extensive stress tests in order to attempt to evaluate the impact of a Lehman failure on markets such as the CDS market and it believes the systemic risk is quantifiable and lower than the risk that was posed by the imminent collapse of Bear back in March. Regulators have also evaluated the risk mitigation strategies put in place by other banks and the authorities believe them to be robust. That suggests the risk that a Lehman collapse could trigger a domino effect of failures at other financial institutions ought not to be great.

September 14, 2008 – http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/f3586ede-80ca-11dd-82dd-000077b07658.html#axzz1mXeJ33ET

Mr Paulson believes that the systemic risks associated with the potential failure of Lehman have been reduced because the market has had time to prepare for its possible demise, and a new Fed funding facility would assist an orderly unwinding of its positions.

February 15, 2012 – http://blogs.channel4.com/faisal-islam-on-economics/eurozone-reaches-its-lehman-moment-as-germany-insults-greece/16278

All the while, the chatter in euro policy circles, as I wrote on Monday, is that the Greek rot will not infect the rest of the euro area. A default could be managed. Even the odd French bank has managed to dispose of much of its exposure. We’ve had months to prepare. And, so the Lehman moment comes full circle. Three and a half years ago we were told exactly the same by Hank Paulson and co re Lehmans: The system, we were told, was strong enough. Finns, Dutch and some Germans increasingly think the same about a Greek default.

With the biggest economic crisis since the Great Depression continuing to slowly unfold, one of the most surprising consequences has been a non-event: the dearth of high-quality economic theorizing in leftist groups. [1] This is in spite of the opportunity the crisis presents for alternative economies, and in spite of the economic conundrum that developed economies find themselves in: too indebted for stimulus and too weak for austerity. This differend between austerity and stimulus indexes the insufficiency of either and yet few have taken up the necessity of thinking proper alternatives.

The leftist response to the economic crisis has instead been mostly been to focus on piecemeal reactions against government policies. The student movement arose as a response to tuition fee and EMA changes; the right to protest movement arose as a response to heavy-handed police treatment; and leftist parties have suggested a mere moderation of existing government policies. The project to bring about a fully different economic system has been shirked in favour of smaller-scale protests. There is widespread critique, but little construction.

Admittedly, the left is not entirely devoid of high-level economic theorizing. Rather, the more specific problem is that those few who do such work are a relatively tiny minority and are typically marginalized within the leftist scene. The attention and effort of the leading intellects of leftism (at least in the UK) are on social issues, race issues, rights issues, and identity issues. All important, to be sure, but there is no equivalent attention paid to economic issues.