This is a post in our EU referendum forum. Click here for the introduction with links to all the contributions.

Our final contributor is Catherine Goetze, Senior Lecturer in Global Studies at the University of Sussex. Catherine is fluent in three languages and has lived and worked in various countries in Europe, America and Asia. Her research focuses on the sociology of global and transnational politics. Catherine’s book, The Distinction of Peace, on the sociology of peacebuilding is forthcoming this summer with the University of Michigan Press. Her publications can be found on her academia.edu page and she blogs occasionally at www.catherinegoetze.org/blog.

Our final contributor is Catherine Goetze, Senior Lecturer in Global Studies at the University of Sussex. Catherine is fluent in three languages and has lived and worked in various countries in Europe, America and Asia. Her research focuses on the sociology of global and transnational politics. Catherine’s book, The Distinction of Peace, on the sociology of peacebuilding is forthcoming this summer with the University of Michigan Press. Her publications can be found on her academia.edu page and she blogs occasionally at www.catherinegoetze.org/blog.

‘Reinvigorating’ sounds like spring, youth, detox and fun… so, who would not want to participate in ‘reinvigorating democracy’? And yet… the problem with the left-wing case for Brexit is that it remains utterly unclear why such a their proposed renaissance of democracy is predicated on Brexit. Contrary to Lee Jones I believe that of all political crucial moments the referendum of 23 June seems the most unlikely opportunity to re-invent democracy. Whether they like it or not, left-wing Brexiters are in the same boat as nationalists across Europe, and for two reasons. Brexit already bears the enormous risk of strengthening the UK’s and Europe’s nationalist and right-wing forces simply by setting a precedent. More importantly, however, left-wing Brexiters will only reinvigorate nationalism and not democracy because they are unable to identify the acting subject of their political project.

The rise of right-wing nationalism in Europe is real

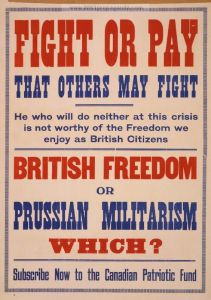

Left-wing Brexiters haughtily dismiss the risk of Europe’s fascism as betrayal and ‘fear mongering’. Yet, the danger is real: In the Austrian presidential elections the right-wing candidate missed victory by 0.6%. If last year’s regional elections in France had been the first round of presidential elections, Marine Le Pen would have been one of the ‘dual’ candidates of the second round. In Germany, where right-wing nationalist discourses have long been taboo, the ‘Alliance for Germany’ has made a spectacular entry into several federal state parliaments; currently, the same party would receive 11% in federal parliamentary elections, hence becoming ‘king maker’ in parliament. The situation is the same in almost every single European country, from Sweden (13% for Sweden Democrats) and Denmark (21% for Danish People Party) in the North to Hungary (21% for Jobbik) in the East and Greece (7% for Golden Dawn) in the South. Although they didn’t win any seats, UKIP won 12.9% of votes in last year’s parliamentary elections.

The rise of right-wing nationalist parties cannot be easily explained away with conspiracy theories that this all is elite manipulation of masses; on the contrary, it is one response to the same crisis of politics that also generated the loss of confidence in the EU. Such crisis moments are nothing new so a look at historical experience might help explain what is at stake now.

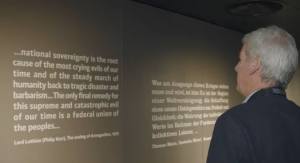

Tragedy and farce of history: Democracy’s unravelling in Weimar

History does not repeat itself, that’s true, yet it is timely to remind democrats in Europe just how much this situation looks like the final years of the Weimar Republic. In the November 1932 elections, the NSDAP became the strongest party with 33.1% yet this alone did not assure Hitler’s appointment as chancellor. Crucially, all those political groupings whose first objective was to disavow established parties and Weimar’s democracy were complicit in his appointment; and that includes, indeed, everyone, even left-wing parties and public intellectuals (Carl von Ossietzky, Karl Kraus, Kurt Tucholsky, Bertolt Brecht, etc). Of course, they were horrified by the Nazis and many were subsequently killed or exiled; nevertheless, it needs to be remembered that in the early 1930s they did little to save the Weimar Republic which they found insufficient in too many ways: inegalitarian, bourgeois and capitalist, too removed from people’s real concerns, corrupt and ridiculously bureaucratic. “Germany is the only country where the lack of political competence is rewarded with the highest offices,” commented Carl von Ossietzky with dismay on elections in the 1920s.

The NSDAP’s rise to power was the final stage of popular disaffection with the Weimar Republic which was mainly due to the dissociation of representative institutions and Germany’s social structures. After the disaster of the First World War, the end of monarchy and the economic turmoil of the 1920s, political parties and social classes did not divide up neatly along party lines. Both sides of the fundamental political question, ‘who gets what?’, were disputed as Germans were desperately seeking Weimar’s demos. Communists asked whether workers were Germans or universal proletarians. Inversely, was the bourgeoisie part of the people or its (international and/or Jewish) enemy? Anti-Semites asked if Jews could be part of ‘us’, and liberal Jews rejected the idea that East-European orthodox Stedtl Jewry would be part of the civilized German nation. ‘Völkisch’ nationalists and historians argued about whether Romanian-speaking Suabians belonged to Germany and if, indeed, language and culture was the decisive criteria, then what about Austrians and Alsatians? Rhinelander Catholics had serious doubts that Protestant Prussian Junkers were really part of the German nation; and the Junkers themselves contended that they were the same kind of Germans as their land labourers…

The end of the Weimar Republic is not a tale of nationalism as external evil force; Nazism was home grown. Yet it was in no way specific to Germany. The Weimar Republic died because those who should have been its subject refused to recognize this democracy as theirs, and everyone did so for their own good reason.

The crisis of politics is not a matter of spatial distance

The contemporary lack (or loss) of confidence in the European Union is symptomatic of a crisis of politics that resembles the Weimar experience. If the EU is singled out as ‘undemocratic’, then not because of its institutions. In fact, constitutionally, the EU offers more opportunities to participate in legislative processes than the UK. What is questioned is the EU’s capacity to ‘truly’ represent the European demos. Brexiters deny this and reclaim their own: ‘we’, ‘I’ or ‘us’ want to decide and make politics, tackle the challenges ahead. They demand to reduce the ‘scale’ and to bring politics close to home (particularly well expressed in the juxtaposed movement words of the leave campaign: ‘Leave! Take back!’). This is Lee Jones’ plea. Its emotiveness, however, eludes the question of who the ‘we’ are. And yet, this is a crucial question: Who is the subject of that reinvigorated democracy?

Lee’s proposal, the national scale, is conveniently agentless. He explains that the national scale ‘is far smaller than the regional scale, local actors have a greater sense of mutual identification, and the structures of representative democracy, however flawed, do exist’. Who local actors are and who they represent, and if this representation is warranted remains obscure. The underlying assumption is that the crisis of representative democracy is simply a matter of spatial distance.

Yet, the crisis of representative democracy is a matter of socio-political, cultural and ideational-identitary distance. The causes for the dissociation of citizens and representation are manifold and by no means reducible to neoliberal governance. Enormous social transformations have dissolved those collective identities and social hierarchies which have shaped the party political structure of European democracies. These social transformations do not only involve the neoliberal dismantling and financialisation of the welfare state and public services, but also the accompanying shift from manufacturing, mining and agriculture to service industries, the introduction of new forms of production and organization, the participation of women in the workforce and the resulting changes in gender roles and families, the rise of ‘alter’ politics like queer or post-colonial politics, changes in education, the heightened mobility of Europe’s and global populations, the inversed age pyramid, the rising awareness and urgency of global environmental problems, and the changed nature of knowledge and communication.

Consequently, nations and social classes are not the ‘self-identifying collectivities marked by a common purpose and some sort of ethos’ anymore (Tormey 2015, 73). Societies have become infinitely more differentiated and ‘intelligible only as the result of aggregation and the overlapping of particularities’ (Rosanvallon 2012, 222). For the nation state the consequence is, as Tormey says, that ‘[…] we are left with an increasingly random assortment of individuals sharing territory, not community’ (op.cit.).

The crisis of representative democracy is, indeed, a crisis of representation in its double sense of delegation of decision-making power and of the interpretation of the citizen’s persona. Citizens more and more often do not wish to delegate their participation but want to act themselves; the tides of large social movements like Attack, the World Social Forums, Occupy or the current Nuit Debout movement in Paris clearly show that complexification, social individualization and political pluralisation have not resulted in apathy.

In the sense of impersonating the citizen, most people find it increasingly difficult to identify with any of the established political parties, politicians and other political organizations like labour unions, whether on local, national or European level. Political identities are not anymore those IKEA flat packs of class politics; rather political identities have become more fluid, diverse, multidimensional and, also, more globalized. Political identities often transcend predefined geographical spaces with citizens engaging in acts of political solidarity with communities in far-away places or addressing problems of transnational scale.

The missing democratic subject of the national scale

Given this complexity, fluidity and globality, who is comprised in the left-wing Brexiters’ ‘national scale’? Is the subject of national scale democracy the ethnic Briton (and then the English, Welsh, Scottish, Irish, too? And only the Protestant Irish or alos the Catholic Irish?), the people who live in Great-Britain no matter their original national belonging, only those people who think they belong (how will we know?), or those people who are affected by the political decisions taken whether they reside in Great-Britain or not, those who contribute constructively to the politics of national scale (and then what does that mean)?

The left-wing project of national rescaling needs to answer these questions beyond simply rejecting the EU representational mechanisms. The default option is the UKIP one: the white, English, male, straight, authoritarian tabloid reader (if he reads at all). Not only exactly the kind of citizen who is most unlikely to support a left-wing experiment in reinvigorating democracy.

As Rosanvallon so concisely says: “One of the most important transformations in our societies reside in the fact that the ’mode of production’ of generality has been transformed. Traditional regimes of generality were conceived in a unitary and aggregate sense […] while present-day generality more often has to be understood as rooted in the partial parallelism of singularities” (Rosanvallon 2012, 222). People’s political and social choices are not made in two-dimensional hierarchies anymore but in three-dimensional, variable, movable and multiple spaces that might or might not include the national scale. This makes politics so much more disorderly, erratic, singularized, glocalized and multifaceted. The attractiveness of right-wing parties resides in their capacity to seemingly reduce this multiplicity by replacing it with a simple binary: in or out. They, indeed, rescale complexity to linear two-dimensionality: White vs. Brown, Christian vs. Muslim, Occident vs. Orient, Native vs. Immigrant, and National vs. European. Being defined in opposition to the transnational and globalizing political project of European integration, Lee Jones’ ‘rescaling’ does not look any different.

There is, certainly, much wrong with the EU. Without doubt, there are still many emancipatory struggles to fight in Europe. Clearly, the project of European federalism is ill designed to respond to the crisis of politics. Yet, although the geometrics of politics have changed, these changes do not follow the linear patterns of the old nation-state’s socio-political structures. Although the identity crisis of the EU shows that recalibration of identity and politics is in order, it is not national rescaling that will reinvigorate democracy; particularly not if the rescalers are not able to positively identify the democratic subject. National rescaling can only reinvigorate nationalism, that’s all. So, if we want to re-create spaces for democratic innovation, it is not by ‘rescaling’ the horizon of possible participation(s) that this will happen.

Our next guest contributor to the EU forum is

Our next guest contributor to the EU forum is