A guest post from Knud Erik Jørgensen. Knud Erik is Professor of Political Science at Aarhus University and the author of many works on European foreign policy, the European Union and European IR theory. He is also former Chair of the ECPR Standing Group on International Relations (2010-2013) and current President of the Governing Council of the European International Studies Association (EISA). This is the first in a short series on naming, representation and power in the discipline of IR.

In a Duck of Minerva blogpost about the 9th Pan-European Conference on International Relations, Cai Wilkinson got most things wrong and three things right. Regarding the latter, the conference and section chairs did indeed manage to produce the probably most diverse programme in the world and they have rightly been highly praised for this accomplishment. I can therefore imagine it took Saara Särmä, the Tumblr artist/activist and admirer of David Hasselhoff a really long search to find something to admonish but then, finally, in a moment of triumph, she spotted 18 of the 32 meeting rooms. Second, greater diversity in organisational structures does not necessarily result in a different politics. This is probably correct but does not demonstrate much insight into policy-making processes within associations or address the issue why one would expect that greater diversity in governance structures would produce a politics that is favoured by Wilkinson. Third, diversity does not just exist along a single axis and the naming of rooms in Sicily illustrates neatly how multiple axes of diversity produce numerous encounters and compete for attention and space.

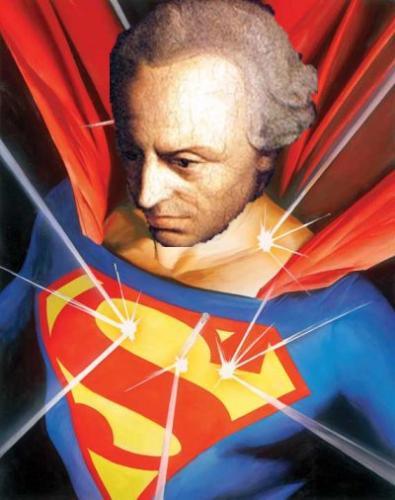

The Congrats, You Have An All-Male Panel! Tumblr.

Wilkinson got most things wrong and therefore claims injury and insult. The rooms in question were not renamed but named. If Wilkinson had asked the organizing committee or for that matter attended the conference she could have learned that 18 converted guest rooms had numbers but got names. Room 5115 became Zimmern and room 5114 became Wolfers, etc. During the conference some panel rooms were unofficially renamed.