But I suspect it’ll get slightly fewer views than that other video…

Colonialism

Kony 2012 and The Choir of Saviors: You got a song you wanna sing for me?

You got a song you wanna sing for me?

Sing a song, singing man.

Sing another song, singing man.

Sing a song for me.

One for the pressing, two for the cross,

Three for the blessing, four for the loss.

Kid holdin’ a weapon, walk like a corpse

In the face of transgression, military issue Kalash

Nikova or machete or a pitchfork.

He killing ’cause he feel he got nothin’ to live for

In a war taking heads for men like Charles Taylor

And never seen the undisclosed foreign arms dealer.

Thirteen-year-old killer, he look thirty-five,

He changed his name to Little No-Man-Survive.

When he smoke that leaf shorty believe he can fly.

He loot and terrorize and shoot between the eyes.

Who to blame? Its a shame the youth was demonized.

Wishing he could rearrange the truth to see the lies

And he wouldn’t have to raise his barrel to target you,

His heart can’t get through the years of scar tissue.

-“Singing Man“, The Roots

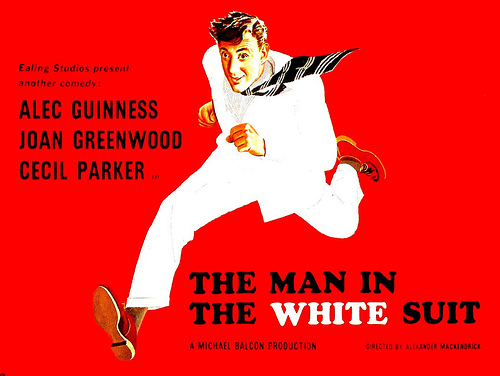

60 million people and counting have now heard about Invisible Children’s “Kony 2012“. Criticism of the group has been substantial and judicious. The group has defended themselves. Humorous memes are proliferating. Over-exposure has already begun to create awareness fatigue. Yet there is a serious issue largely unaddressed: the most troubling elements of the “Kony 2012” phenomenon are not unique to Invisible Children, but reflect serious moral and political problems with the pursuit of international criminal justice, and in particular the mission and politics of the International Criminal Court and their controversial prosecutor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo.

To put it bluntly: while Jason Russell addresses his audience in the same way he addresses his five-year-old son Gavin, which is clearly inappropriate given the complexity of the issues he’s asking us to consider, Russell’s framing of the evil of Joseph Kony and “our” responsibility to stop him is importantly similar to the narrative of international criminal law, and Ocampo in particular. We should not be too quick to denounce the moral idiocy of Russell as a personal failing – his sentimental and messianic film represents a revealing apotheosis rather than a transgressive break from our sense of international justice. There are unpleasant resonances between Russell and Ocampo – the ICC prosecutor has already praised the group, saying,

“They’re giving a voice to people who before no-one knew about and no-one cared about and I salute them.”

Human Rights Contested – Part II

This is a continuation of my previous post…

Who Are Human Rights For?

All of the authors take account of the ambiguous history of human rights, in which they can be said to have inspired the Haitian, American and French revolutions, while also justifying the counterrevolutionary post-Cold War order dominated by the United States. Yet recognising this ambiguity without also acknowledging the distinctive reconstruction of contemporary human rights that makes them part of a neo-liberal international order and the unequal power that makes such a quasi-imperial order possible would be irresponsible. A primary contribution made collectively by these texts is that they clearly diagnose the way human rights have been used to consolidate a particular form of political and economic order while undercutting the need for, much less justification of, revolutionary violence. Williams says of Amnesty International’s prisoners of conscience, who serve as archetypal victims of human rights abuse,

the prisoner of conscience, through its restrictive conditions, performs a critical diminution of what constitutes “the political.” The concept not only works to banish from recognition those who resort to or advocate violence, but at the same time it works to efface the very historical conditions that might come to serve as justifications – political and moral – for the taking up of arms.

Human rights, then, are for the civilised victims of the world, those abused by excessive state power, by anomalous states that have not been liberalised – they are not for dangerous radicals seeking to upset the social order.

Human Rights Contested – Part I

This post (presented in two parts) is drawn from a review article that will be forthcoming in The Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, which looks at a recent set of critical writings on human rights in order to consider the profound limitations and evocative possibilities of the contested idea and politics of human rights.

Human Rights in a Posthuman World: Critical Essays by Upendra Baxi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Surrendering to Utopia: An Anthropology of Human Rights by Mark Goodale. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009.

The Divided World: Human Rights and Its Violence by Randall Williams. Minneapolis, MN and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

After Evil: A Politics of Human Rights by Robert Meister. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2011.

The central tension of human rights is that they propagate a universal and singular human identity in a fragmented political world. No one writing about human rights ignores this tension, but the most important question we face in judging the value of human rights is how to understand this tension and the divisions it creates. The expected divisions between good and evil, between moral universalists and dangerous relativist, between dignified interventionists and cowardly apologists, have long given shape to human rights, as both an ideal and a political project. Seeing the problems of (and for) human rights in these habituated ways has dulled our capacity for critical judgment, as few want to defend evil or violent particularisms or advocate passivity in the face of suffering. Even among serious and determined critics our inherited divisions are problematic (and increasingly over rehearsed), whether we think of human rights as the imposition of Western cultural values, or in terms of capitalist ideology serving the interests of neo-liberal elites, or as an expression of exceptional sovereign power at the domestic and global levels. The ways that these divisions deal with the tension at the heart of human rights misses the ambiguity of those rights in significant ways.

Rather than trying to contain the tensions between singularity and pluralism, between commonality and difference, in a clear and definitive accounting, the authors of the texts reviewed here allow them to proliferate. Rather than trying to resolve the problem of human rights, they attempt to understand human rights in their indeterminate dissonance while exploring what they might become. To create and invoke the idea of humanity is not a political activity that is unique (either now or in the past) to the ‘West’. The people most dramatically injured by global capitalism sometimes fight their oppression by innovating and using the language and institutions of human rights. Political exceptions – the exclusion of outsiders, humanitarian wars and imperialist conceits – are certainly enabled by the same sovereign power that grants rights to its subjects, which is a metaphorical drama all too easily supported by human rights, but it is only a partial telling of the tale, a telling that leaves out how human rights can reshape political authority and enable struggles in unexpected ways. The work of these authors pushes us to reject the familiar divisions we use to understand the irresolvable tension at the centre of human rights and see the productive possibilities of that tension. If human rights will always be invoked in a politically divided world, and will also always create further divisions with each declaration and act that realises an ideal universalism, then our focus should be on who assumes (and who can assume) the authority to define humanity, the consequences for those subject to such power, and the ends toward which such authority is directed. Continue reading

Colouring Lessons: Reflections On The Self-Regulation Of Racism

A guest post, following Srdjan’s and Robbie’s contributions on the meaning and structure of contemporary racism, by Elizabeth Dauphinee. Elizabeth is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at York University in Toronto. She is the author of The Ethics of Researching War: Looking for Bosnia and co-editor of The Logics of Biopower and the War on Terror: Living, Dying, Surviving. Her work has appeared in Security Dialogue, Dialectical Anthropology, Review of International Studies and Millennium. Her current research interests involve autoethnographic and narrative approaches to international relations, Levinasian ethics and international relations theory, and the philosophy of religion.

A guest post, following Srdjan’s and Robbie’s contributions on the meaning and structure of contemporary racism, by Elizabeth Dauphinee. Elizabeth is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at York University in Toronto. She is the author of The Ethics of Researching War: Looking for Bosnia and co-editor of The Logics of Biopower and the War on Terror: Living, Dying, Surviving. Her work has appeared in Security Dialogue, Dialectical Anthropology, Review of International Studies and Millennium. Her current research interests involve autoethnographic and narrative approaches to international relations, Levinasian ethics and international relations theory, and the philosophy of religion.

The idea promulgated by Bet 115 that racism can and will meet its demise in a few short decades is based on the assumption that humans are self-regulating creatures, capable of recognizing and assessing their beliefs in an objective way and making appropriate corrections as needed. In order to explore this assumption, we need to inquire into the relationship between the self as an individual entity, capable of navigating and responding to the external world in an objective, disinterested way, and the social sphere, which may so entirely constitute us that we are incapable of thinking beyond the ‘texts’ (or scripts) of our socio-cultural milieus. In simpler terms, the question is: do we create the world, or does the world create us?

In order to rightly consider this question, it is important to understand the implications of the answers one might be tempted to choose. It is also important to realise that each of us has a personal investment in the answer we might make. If we are individuals capable of willfully altering the world, then it makes sense to say that we can overcome racism (yet one is left with a lingering sense of bewilderment over why we have not done so). If we are fundamentally shaped and inextricably bound by the social sphere in which our ideas are formed, then we might lack the agency to escape the racism that seems to form a cornerstone of the institutions of our historico-political condition. Of course, there are few who would accept that our ability to self-regulate is an either/or proposition. Rather, it is probably better to understand it as a ‘both/and’ state of affairs. In short, we shape and are shaped by the worlds we occupy. How, exactly, this is so is difficult to pick apart and navigate despite all of social science’s failed attempts to sharpen the distinction between the self and the worlds the self occupies. It inevitably flattens the complexity of social relations, and often ignores the tensions and contradictions that animate people’s views and beliefs. By way of example, let us consider the question with which we began: are we, or are we not, self-regulating creatures? The very structure of the question assumes that one will make answer either one way or the other. It leaves little room to suggest that both propositions are true, but in different ways and with different implications.

Colouring Lessons: Race Is A Structure Of Oppression, And Is Alive And Well

Race is a structure of oppression. So long as the structure remains, so does race. However, while there is plenty of talk about ethnicity and social cohesion, pathological cultures, and broken communities, race is usually mentioned only in its disavowal. And racism? Few would profess to that habit; most would comfortably label racism as a reactionary attitude. But to what imaginary golden mean? It is a privilege to believe that racism is a reaction rather than a catalysing agent of oppression. Meanwhile, all of us are variously implicated in this structure of oppression called race.

Race is a structure of oppression. So long as the structure remains, so does race. However, while there is plenty of talk about ethnicity and social cohesion, pathological cultures, and broken communities, race is usually mentioned only in its disavowal. And racism? Few would profess to that habit; most would comfortably label racism as a reactionary attitude. But to what imaginary golden mean? It is a privilege to believe that racism is a reaction rather than a catalysing agent of oppression. Meanwhile, all of us are variously implicated in this structure of oppression called race.

Even on the left, race is seen to be somewhat passé, and happily so now that the next world crisis in capital accumulation has arrived and we can all finally re-focus on the real thing: class. But what is the difference between race and class? Is it the difference between superstructure and base? Race does involve identification, both in order to oppress and in order to redeem. Yet in this respect, it is no more or less an identity than class. With the exception of Black Marxism, what the left has historically been unable or unwilling to consider is that, as a structure of oppression, race runs deeper than class.

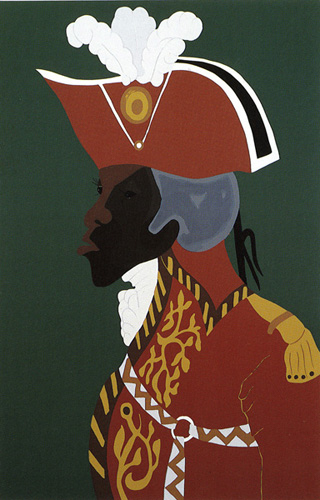

Marx’s masterful hermeneutic shift from contract to class involved leaving behind the realm of exchange – wherein all things were of equivalent value and all transactions were equitable – and entering into the realm of production – wherein value was consistently expropriated and relations were exploitative. Nevertheless, in the colonial world, Marxism was more often used as a weapon for struggle and less so as a faith to guide contemplation. One reason for this engagement is that class exploitation never quite explained the reality of oppression experienced under the colonial exigencies of the world market.

In truth, Marx did not shift his hermeneutic far enough from liberalism and its obsession with civil society. Continue reading

Looking Beyond Spring for the Season: Echoes of Time Before Tahrir Square

This is the fifth and last part in a series of posts from Siba Grovogui, Professor of International Relations and Political Theory at John Hopkins University. The first part is here; the second here; the third here; the fourth here. The series considers the character and dimensions of the tension between the African Union and ‘the West’ over interventions in Africa. As before, responsibility for visuals adheres solely to Pablo K.

It would be disingenuous to relate events in North Africa and the Middle East (or MENA) today without reference to the media. Here too, there are many possible angles to examine. I will focus on the institutional support that the media provide in shaping consensus in support of foreign policy. In this regard, so-called mainstream Western media and networks (BBC, CNN, Fox, RFI and the like) have played a significant role in generating domestic support for the Libyan campaign. The media find themselves in the contradictory positions of both providing sustenance to foreign policy rationales and reporting on government actions. In this role the media either wittingly or unwittingly assumed the position of justifying contradictory Western foreign policy aims while trying to satisfy the needs of their audiences (especially domestic constituencies and home governments) for information from the front. Consistently, the media often generate sympathy for foreign actors or entities that either support Western interests or have affinities for Western values.

It would be disingenuous to relate events in North Africa and the Middle East (or MENA) today without reference to the media. Here too, there are many possible angles to examine. I will focus on the institutional support that the media provide in shaping consensus in support of foreign policy. In this regard, so-called mainstream Western media and networks (BBC, CNN, Fox, RFI and the like) have played a significant role in generating domestic support for the Libyan campaign. The media find themselves in the contradictory positions of both providing sustenance to foreign policy rationales and reporting on government actions. In this role the media either wittingly or unwittingly assumed the position of justifying contradictory Western foreign policy aims while trying to satisfy the needs of their audiences (especially domestic constituencies and home governments) for information from the front. Consistently, the media often generate sympathy for foreign actors or entities that either support Western interests or have affinities for Western values.

This role is not without a cost, especially when foreign policy actions, including wars, fail to attain their objectives. When the outcome of foreign policy proves disastrous, Western media also have an inexhaustible capacity to either ignore their prior support for the underlying causes or to reposition themselves as mere commentators on events over which they had no control or could not prevent. Increasingly, these tendencies have spread around the world as evidenced in the techniques and styles that have propelled the Qatari-based Al Jazeera into prominence as key contender in the emergent game of production, circulation, and consumption of foreign policy-concordant images for their affective and ideological effects.

So it is not surprising that the backdrop and background scenarios for most reporting on the 2011 revolts in MENA are dimensions of Orientalism, of which they are many. But the most constant is one of autocratic ‘barbarism’. In this regard, the discourses and media techniques for creating and supporting sympathetic figures are just as constant (or invariable) as Western states rationales for intervention. The media-hyped stories of Oriental despotism that preceded Operation Desert Storm, when the US expelled Iraq from Kuwait, have provided the template. During that event, for instance, media feted their viewers with stories of invading Iraqi hordes storming through hospital only to disconnect incubators and let helpless infants die a slow death. These and many stories of heroic bids by US soldiers to prevent such barbarism were later discredited but not the other horrific stories which convinced US citizens of the need to wage war on Saddam Hussein’s occupying army. In the Libyan case today, one of the earlier images of the aura of impunity created by Gaddafi was that of a Libyan female lawyer who was allegedly raped by Gaddafi’s forces. There was also a reported event of military takeover of a hospital.

Looking Beyond Spring for the Season: Democratic and Non-Democratic Cultures

This is the fourth part in a series of five posts from Siba Grovogui, Professor of International Relations and Political Theory at John Hopkins University. The first part is here; the second here; the third here. The series considers the character and dimensions of the tension between the African Union and ‘the West’ over interventions in Africa. As before, responsibility for visuals adheres solely to Pablo K.

It is not accurate to say that the African Union has been indifferent to the conflict in Libya. If there has been silence in Africa, it has to do with the extent to which the ‘maverick’ Colonel (Gaddafi) has angered some of his peers over the years by interfering in the affairs of such states as Nigeria, Liberia, Burkina Faso, Sierra Leone and others, with disastrous effects. Even when, as in Sudan and Uganda, officeholders have welcomed his entreaties, large segments of the populations have not appreciated them. Yet, regardless of their personal views of Gaddafi and their political differences with him, African elites and populations have yearned for a more positive, conciliatory, and participatory solution to outright regime change or the removal of Gaddafi preferred by the West. This variance, I surmise, comes from a positive understanding of postcoloniality that include forgiveness, solidarity, and democracy and justice, as exhibited in post-apartheid South Africa and post-conflict Liberia, Angola, Mozambique, and the like.

It is not accurate to say that the African Union has been indifferent to the conflict in Libya. If there has been silence in Africa, it has to do with the extent to which the ‘maverick’ Colonel (Gaddafi) has angered some of his peers over the years by interfering in the affairs of such states as Nigeria, Liberia, Burkina Faso, Sierra Leone and others, with disastrous effects. Even when, as in Sudan and Uganda, officeholders have welcomed his entreaties, large segments of the populations have not appreciated them. Yet, regardless of their personal views of Gaddafi and their political differences with him, African elites and populations have yearned for a more positive, conciliatory, and participatory solution to outright regime change or the removal of Gaddafi preferred by the West. This variance, I surmise, comes from a positive understanding of postcoloniality that include forgiveness, solidarity, and democracy and justice, as exhibited in post-apartheid South Africa and post-conflict Liberia, Angola, Mozambique, and the like.

In opting for negotiated mediation and a new constitutional compact, therefore, the African Union (or AU) aimed to foster a different kind of politics in Libya – admittedly one that has escaped many of the states endorsing that position. As articulated by Jean Ping, the Secretary General of the AU, the Libyan crisis offered an opportunity “to enhance a self-nourishing relationship between authority, accountability and responsibility” in order to “reconstitute African politics from being a zero sum to a positive sum game” toward one “characterized by reciprocal behavior and legitimate relations between the governors and the governed.” Mr. Ping added two other dimensions to his vision. The first is an acknowledgement that events in Libya point to the fact that all Africans “yearn for liberty and equality’ and this yearning is “something more consequential than big and strong men.” The second is that Africa’s destiny should be shaped by Africans themselves based on an actualized “sense of common identity based, not on the narrow lenses of state, race or religion, but constructed on Africa’s belief in democracy, good governance and unity as the most viable option to mediate, reconcile and accommodate our individual and collective interests.”

Coming from a politician, these words may read like slogans. But the uniform refusal of the AU to endorse Western intervention tells another story. Continue reading

Looking Beyond Spring for the Season: The West, The African Union, and International Community

This is the third part in a series of five posts from Siba Grovogui, Professor of International Relations and Political Theory at John Hopkins University. The first part is here; the second here. The series considers the character and dimensions of the tension between the African Union and ‘the West’ over interventions in Africa. As before, responsibility for visuals adheres solely to Pablo K.

The oblivion of commentators to these possible African objections has been less than helpful to understanding the actualized Western intervention itself; emergent African ideas on democracy and security; and the actual place of international morality in international affairs. Underlying the African apprehension to military intervention is a long-standing tension between international organizations that represent Africa, on one hand, and self-identified representatives of the West, on the other, over the meaning of international community as well as the source, nature, and proper means of implementation of the collective will. The dispute over the meaning of international community and the collective will has been particularly salient in Africa because, as a political space, Africa has been more subject to military interventions than any other geopolitical space in the modern era. These interventions have reflected contemporaneous relations of power, permissible morality, and objects of desire: from proselytism to fortune-seeking, trade, extraction of raw material, and the strategic pursuit of hegemony. Indeed, it is hard to remember a time since the onset of the slave trade when there was no open conflict between the majority of its states and the West over some dimensions of global governance that implicated the notion of the commons or international community.

The oblivion of commentators to these possible African objections has been less than helpful to understanding the actualized Western intervention itself; emergent African ideas on democracy and security; and the actual place of international morality in international affairs. Underlying the African apprehension to military intervention is a long-standing tension between international organizations that represent Africa, on one hand, and self-identified representatives of the West, on the other, over the meaning of international community as well as the source, nature, and proper means of implementation of the collective will. The dispute over the meaning of international community and the collective will has been particularly salient in Africa because, as a political space, Africa has been more subject to military interventions than any other geopolitical space in the modern era. These interventions have reflected contemporaneous relations of power, permissible morality, and objects of desire: from proselytism to fortune-seeking, trade, extraction of raw material, and the strategic pursuit of hegemony. Indeed, it is hard to remember a time since the onset of the slave trade when there was no open conflict between the majority of its states and the West over some dimensions of global governance that implicated the notion of the commons or international community.

The postcolonial era has not brought about any change to this situation. Since the end of World War II and the institution of the United Nations system, the plurality of African political entities have confronted self-appointed representatives of the West over the ethos of UN procedures (involving transparency and open access to the channels of decision-making) and the mechanisms of dispute mediation (including the determination of the principles and applicability of humanitarian interventions in a number of cases). One need only recall the political, legal, and military confrontations between African states and former Western colonial powers over Apartheid South Africa’s mandate over South West (which involved the legality and morality of colonial trusteeship); the French war on Algeria (which involved the legality and legitimacy of settler colonialism); the wars of decolonization in the former Portuguese colonies of Angola, Guinea Bissau, and Mozambique (which involved the principles of majority rule through open elections which communists might win); the unilateral declaration of independence by the white minority in Southern Rhodesia (which involved the principle of white-minority rule in postcolonial Africa); and the legality and morality of apartheid (which involved the principle of self-determination and majority rule). The underlying antagonisms contaminated deliberations throughout the UN system (particularly General Assembly proceedings) and involved all major issues from the Palestine Question to the Law of the Sea to other matters of trade and intellectual property. They reached a climax at the time of exit of the US and Great Britain from UNESCO, which was then directed by Ahmadou Mathar Mbow, a Senegalese diplomat and statesman.

These and other contests have shared a few singular features. One is a Western insistence on representing the essential core and therefore will of something called international community. In any case, the label of international community has often been reserved for Western entities in relations to others, who remain the object of intervention on behalf of the international community. This is to say that the term ‘international community’ has had political functionality in relations of power and domination in which Europe (and later The West) subordinated ‘Africa’. The relevant tradition can be traced back to the opening moments of the modern era, particularly during the ascension of The West to global hegemony. While it has undergone changes over time, the embedded imaginary of international community and its will have been built around artificially fixed identities and politically potent interests. Accordingly, the identity of the West, and therefore the international community, flows from a theology of predestination, formally enunciated as the Monroe doctrine in the US or the Mission Civilizatrice in France.

Looking Beyond Spring for the Season: Common and Uncommon Grounds

This is the second part in a series of five posts from Siba Grovogui, Professor of International Relations and Political Theory at John Hopkins University. The first part is here. The series will consider the character and dimensions of the tension between the African Union and ‘the West’ over interventions in Africa. Responsibility for visuals adheres solely to Pablo K.

As I indicated in my last post, the decision by the African Union (or AU) to not endorse the current military campaign in Libya has been mistaken by many observers and commentators alternatively as a sign of African leaders’ antipathy to political freedom and civil liberties; a reflexive hostility to former colonial powers, particularly France and Great Britain; a suspicion of the motives of the United States; and more. The related speculations have led to the equally mistaken conclusion that the African Union is out of step with the spirit of freedom sweeping across the Middle East and North Africa (or MENA). The absurdity of the claim is that the only entity that imposed any outline of solution agreeable to Gaddafi has been the African Union and this is that Gaddafi himself would not be part of any future leadership of the country. But the AU has insisted on an inclusive negotiated settlement. The purpose of this series of essays is not therefore to examine the meaning and implications of the absence of ‘Africa’ on the battlefield of Libya, but to point to the larger geopolitical implications of the intervention for international order, global democratic governance, and the promotion of democratic ideals and political pluralism in the region undergoing revolution and beyond.

As I indicated in my last post, the decision by the African Union (or AU) to not endorse the current military campaign in Libya has been mistaken by many observers and commentators alternatively as a sign of African leaders’ antipathy to political freedom and civil liberties; a reflexive hostility to former colonial powers, particularly France and Great Britain; a suspicion of the motives of the United States; and more. The related speculations have led to the equally mistaken conclusion that the African Union is out of step with the spirit of freedom sweeping across the Middle East and North Africa (or MENA). The absurdity of the claim is that the only entity that imposed any outline of solution agreeable to Gaddafi has been the African Union and this is that Gaddafi himself would not be part of any future leadership of the country. But the AU has insisted on an inclusive negotiated settlement. The purpose of this series of essays is not therefore to examine the meaning and implications of the absence of ‘Africa’ on the battlefield of Libya, but to point to the larger geopolitical implications of the intervention for international order, global democratic governance, and the promotion of democratic ideals and political pluralism in the region undergoing revolution and beyond.

To begin, it is not just ‘Africa’, ‘African indecision’, and ‘African non-Normativity’ that are at stake in the characterization of African actions or inactions. Much of what is construed as ‘lack’ or ‘absence’ in Africa is also intended to give sustenance to the idea of the indispensability of the West – composed on this occasion by France, Great Britain, the United States, and tangentially Canada – to the realization of the central ends of the MENA Spring. The myth of the centrality of the West to the imaginary of freedom everywhere is inscribed in the name given to the events under description. In the US at least, the Arab Spring evokes many other ‘Springs’ all located in the West (including the 1968 Prague Spring or the 1989 collapse of the Soviet Union and its satellite states). Likewise, ‘Jasmine’, the emblem of the Tunisian revolt has been advanced as evocative of the Ukrainian ‘Orange’ and other colour-coded European events. These allusions have justifications but they are seldom evoked comparatively to elucidate the originality and specificity of the MENA revolutions. In this latter regard, even the suggestion of an Arab Spring assumes that the majorities in the countries involved are Arab. This is not always the case in North Africa but Orientalism obliges!

The fact is that the ongoing revolutions in MENA are at once specific and universal in their own ways. Continue reading