(wild bells) A warm Disordered welcome to Wanda Vrasti, who previously guested on the topic of the neoliberal tourist-citizen imaginary, and now joins the collective permanently. And glad we are to have her. Her academic writings thus far include Volunteer Tourism in the Global South: Giving Back in Neoliberal Times (which came out with the Routledge Interventions series a few months ago), ‘The Strange Case of Ethnography in International Relations’ (which caused its own debate), ‘”Caring” Capitalism and the Duplicity of Critique’, and most recently ‘Universal But Not Truly “Global”: Governmentality, Economic Liberalism and the International’.

It’s often been said that this is not only a socio-economic crisis of systemic proportions, but also a crisis of the imagination. And how could this be otherwise? Decades of being told There Is No Alternative, that liberal capitalism is the only rational way of organizing society, has atrophied our ability to imagine social forms of life that defy the bottom line. Yet positive affirmations of another world do exist here and there, in neighbourhood assemblies, community organizations, art collectives and collective practices, the Occupy camps… It is only difficult to tell what exactly the notion of progress is that ties these disparate small-is-beautiful alternatives together: What type of utopias can we imagine today? And how do concrete representations or prefigurations of utopia incite transformative action?

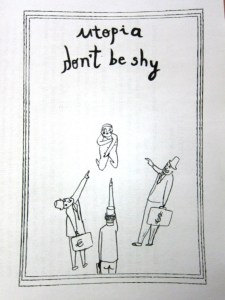

First thing one has to notice about utopia is its paradoxical position: grave anxiety about having lost sight of utopia (see Jameson’s famous quote: “it has become easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”) meets great scepticism about all efforts to represent utopia. The so-called “Jewish tradition of utopianism,” featuring Adorno, Bloch, and later on Jameson, for instance, welcomes utopianism as an immanent critique of the dominant order, but warns against the authoritarian tendencies inherent in concrete representations of utopia. Excessively detailed pictures of fulfilment or positive affirmations of radiance reek of “bourgeois comfort.” With one sweep, these luminaries rid utopianism of utopia, reducing it to a solipsistic exercise of wishing another world were possible without the faintest suggestion of what that world might look like.

But doing away with the positive dimension of utopia, treating utopia only as a negative impulse is to lose the specificity of utopia, namely, its distinctive affective value. The merit of concrete representations of utopia, no matter how imperfect or implausible, is to allow us to become emotionally and corporeally invested in the promise of a better future. As zones of sentience, utopias rouse the desire for another world that might seem ridiculous or illusory when set against the present, but which is indispensable for turning radical politics into something more than just a thought exercise. Even a classic like “Workers of the World Unite!” has an undeniable erotic (embodied) quality to it, which, if denied, banishes politics to the space of boredom and bureaucracy. It is one thing to tell people that another world is possible and another entirely to let them experience this, for however shortly.

Most concrete representations and prefigurations of utopia from the past half century or so have been of the anti-authoritarian sort. Continue reading