A guest post from Vassilios Paipais, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland. Vassilios holds a PhD in International Relations from the LSE and has published in Review of International Studies, International Politics and Millennium, and held various teaching posts at the LSE, SOAS, UCL and the University of Edinburgh. His work focuses on International Relations theory and international political theology. He is also co-founder of Euro Crisis in the Press and Associate to the LSE IDEAS Southern Europe International Affairs programme. You can read his Euro Crisis posts here, as well as follow him on Twitter.

A guest post from Vassilios Paipais, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland. Vassilios holds a PhD in International Relations from the LSE and has published in Review of International Studies, International Politics and Millennium, and held various teaching posts at the LSE, SOAS, UCL and the University of Edinburgh. His work focuses on International Relations theory and international political theology. He is also co-founder of Euro Crisis in the Press and Associate to the LSE IDEAS Southern Europe International Affairs programme. You can read his Euro Crisis posts here, as well as follow him on Twitter.

This post is based on a recently published article in Millennium where he explores the implications of post-foundational political ontology for IR via a reading of Martin Heidegger and Oliver Marchart.

Post-foundational political thought offers the conceptual tools to theorise the experience of dislocation in politics signified by the difference as such between politics and the political. According to Žižek, the political designates the “moment of openness, of undecidability when the very structuring principle of society, the fundamental form of the social pact is called into question” whereas politics describes the positively determined outcome of that process, a “subsystem of social relations in interaction with other sub-systems”. The difference as such between politics and the political implies that any effort to cancel this gap or gloss it over by using ethical, political, juridical or economic arguments is nothing else but an attempt to hegemonise the social by ideologically displacing politics. The political signifies the moment of grounding/de-grounding of the social that is suppressed or forgotten by the operation of politics but can be reactivated at any time through dislocation and antagonism. Politics is incessantly trying to colonise the political but we are each time painfully reminded that an unbridgeable chasm separates the two. It is exactly the irresolvability of this gap that makes politics the name for a paradoxical enterprise which is both impossible and inevitable – which is why none has ever witnessed ‘pure politics’ either. The political cannot be brought about voluntaristically but, whenever we act, it is as if we always activate it or, better, we are always enacted by it. Both gestures of eliminating the force of the political (post-politics) or of introducing it unmediated into politics (total war, revolutionary terror) end up abolishing the political difference and ultimately result in an ideological displacement of politics.

Against this backdrop, I read the sophisticated realism of Hans Morgenthau as a promising but inconclusive attempt at a post-foundationalism political ontology. In fact, I argue that by equally shunning a facile surrender either to the immanence of power (ultra-politics) or to the technologisation of politics (post-politics), Morgenthau’s theory of the political strove to maintain a reflexive fidelity to the logic of political difference as such. At this point, the question naturally arises: why Morgenthau? Isn’t he the archetypical exponent of a tradition that prioritises a static view of international relations and the adoration of power politics? Well, for those who have been following the recent revisionist literature on classical realism, not really; Morgenthau, in contrast, emerges as an apparent candidate to discuss the crisis of foundationalism in (international) political thought and the paradox of its necessity and impossibility, not least because he is one of those rare thinkers that offers no facile solution to, or redemption from, the existential anxiety caused by the interrogation of ultimate foundations in late modernity.

Such an exercise highlights the strong affinities between Morgenthau and critical historicist currents in social and political theory, but this would come as a surprise only to those who equate Morgenthau’s realism with stasis and conservatism and are ignorant of his debt to the thought of Dilthey, Mannheim and Nietzsche. And yet, why inconclusive? Short answer: because of his failure to be radical enough in his Kantian antinomism or, to put it reversely, in his Nietzschean skepticism. And yet, my intention is not to award or withhold credentials of criticality, nor to indict Morgenthau for failing to live up to standards that he never set for himself. On the contrary, in an authentic act of immanent criticism, one does not seek to oppose the other(s) but, instead, to bring out a certain ‘internal contradiction’ to them, in a sense repeat all that they are saying but for an entirely different reason. The purpose of this critique is not to identify shortcomings in Morgenthau’s arguments but to interrogate the ‘transcendental’ conditions of his discourse: that which is in it more than itself. My thoughts on Morgenthau’s unfinished project then should be seen as a propaedeutic towards an investigation of the conditions and challenges involved in practicing international theory as a constant critique of depoliticisation.

Continue reading →

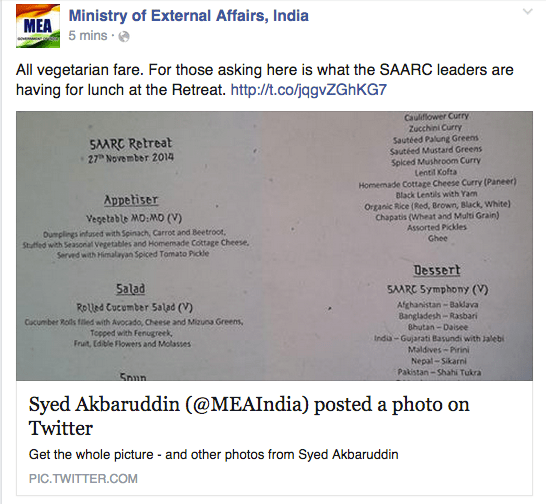

Amit is a PhD student at the Department of Political Science at the National University of Singapore (NUS), and he is working on India’s engagement with Afghanistan from the perspective of Indian identity formation. Previously he worked as a media specialist with the US Embassy in New Delhi and at the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA), New Delhi. He holds an M.A. in South Asian Area studies from SOAS, and is a computer engineer by training.

Amit is a PhD student at the Department of Political Science at the National University of Singapore (NUS), and he is working on India’s engagement with Afghanistan from the perspective of Indian identity formation. Previously he worked as a media specialist with the US Embassy in New Delhi and at the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA), New Delhi. He holds an M.A. in South Asian Area studies from SOAS, and is a computer engineer by training. Medha is a research fellow/doctoral student at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg. Her research focus is on the role of Islam in India’s identity and foreign policy. She previously worked at the IDSA, and also as a journalist in India, Germany, the Netherlands and Canada. She holds an M.A. in Media Studies, jointly from Aarhus and Swansea Universities.

Medha is a research fellow/doctoral student at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg. Her research focus is on the role of Islam in India’s identity and foreign policy. She previously worked at the IDSA, and also as a journalist in India, Germany, the Netherlands and Canada. She holds an M.A. in Media Studies, jointly from Aarhus and Swansea Universities.