Our final post reflecting on the forum itself is from Professor Kimberly Hutchings, she is Professor of Politics and International Relations at Queen Mary University of London. She is a leading scholar in international relations theory. She has extensively researched and published on international political theory in respect to Kantian and Hegelian philosophy, international and global ethics, Feminist theory and philosophy, and politics and violence. Her work is influenced by the scholarly tradition that produced the Frankfurt School and Critical Theory. Previous posts can be found here: Myriam, Joe, Elke, Jillian and Diego. *Note: all images provided by Joe – Kim bears no responsibility for the cheap visual gags!

Ethics as a term encompasses every-day and more specialised meanings. It is used to refer to existing moral commitments, standards and values embedded in actual contexts and influencing or governing practice. It is also used to refer to philosophical justifications of moral standards and values. One encounters ethics in both senses in reflecting on the contributions to ‘Ethical Encounters’. All of these encounters seek to speak to dimensions of practice: war, development, migration, rights claims in the name of humanity. All of them also seek to shift the philosophical assumptions and implications of predominant approaches to international ethics. In summary, they all ask ethical questions about doing ethics in theory and practice. For all of the contributors encountering ethics is itself an ethical encounter. Of course they do not all say the same thing, and in what follows I want to pick out some of the commonalities and some of the differences between them. This will not be in order to resolve or transcend differences, or to develop a synthesis of the views expressed, but rather to bear further witness to what Elke calls the ‘ethicality of ethics’, which I want to suggest is intimately related to unresolvable but also unavoidable questions of authority and judgment.

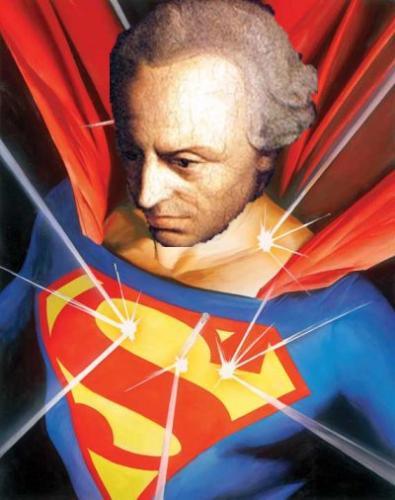

Myriam, Joe, Elke, Jillian and Diego are all against a certain kind of international ethics, which they see as globally dominant in theory and practice in the worlds of the western academy and liberal international policy. They are against ethics understood ultimately as a matter of universal truths, which can be translated into the terms of binding prescriptive rules, laws and codes of practice. It is pretty clear, although he is not necessarily named, that Public Enemy Number One is Kant, with Bentham a close second, followed of course by the recent deontological, contractarian and utilitarian inspired generation of cosmopolitan moral and political theorists and their allies in law and policy.