A guest post from Melanie Richter-Montpetit, responding to the disclosure of the Senate Torture Report in December. Melanie is currently lecturer in international security at the University of Sussex, having recently gained her PhD from York University in Toronto. Her work on issues of subjectivity, belonging and political violence has also been published in Security Dialogue and the International Feminist Journal of Politics.

– Frederick Douglass (1846)[i]

– James Baldwin (1977)[ii]

– Eric Garner (2014)

No, bin Laden was not found because of CIA torture.[iii] In fact, the US Senate’s official investigation into the CIA’s post-9/11 Detention and Interrogation program concludes that torture yielded not a single documented case of “actionable intelligence.” If anything, the Senate Torture Report[iv] – based on the review of more than six million pages of CIA material, including operational cables, intelligence reports, internal memoranda and emails, briefing materials, interview transcripts, contracts, and other records – shows that the administration of torture has led to blowbacks due to false intelligence and disrupted relationships with prisoners who cooperated. What went “wrong”? How is it possible that despite the enormous efforts and resources invested in the CIA-led global torture regime, including the careful guidance and support by psychologists[v] and medical doctors, that the post-9/11 detention and interrogation program failed to produce a single case of actionable data? Well, contrary to the commonsense understanding of torture as a form of information-gathering, confessions made under the influence of torture produce notoriously unreliable data, and the overwhelming majority of interrogation experts and studies oppose the collection of intelligence via the use of torture. This is because most people are willing to say anything to stop the pain or to avoid getting killed and/or are simply unable to remember accurate information owing to exhaustion and trauma.[vi]

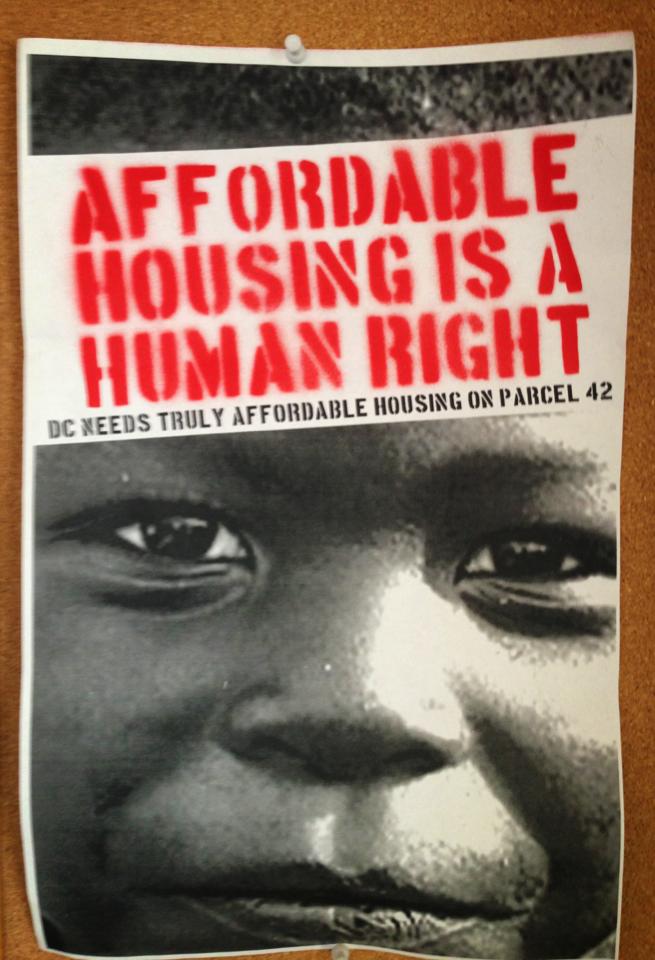

So if torture is known not work, how come, then, that in the wake of 9/11 the U.S. at the highest levels of government ran the risk of setting up a torture regime in violation of international and domestic law? Why alienate international support and exacerbate resentments against “America” with the public display of controversial incarceration practices, as in Guantánamo Bay, instead of simply relying on the existing system of secret renditions? Furthermore, in the words of a former head of interrogations at Guantánamo Bay, most of the tortured and indefinitely detained are “Mickey Mouse” prisoners,[vii] reportedly known not to be involved in or not to have any information on criminal or terrorist activity against the U.S. and its allies. Drawing on previously published work, I will explore this puzzle by addressing two key questions: What is the value of these carceral practices when they do not produce actionable intelligence? And, what are some of the affective and material economies involved in making these absurd and seemingly counterproductive carceral practices possible and desirable as technologies of security in the post-9/11 Counterterrorism efforts?

Against the exceptionalism[viii] of conceiving of these violences as “cruel and unusual,” “abuse” or “human rights violations”[ix] that indicate a return to “medieval” methods of punishment, the post-9/11 US torture regime speaks to the constitutive role of certain racial-sexual violences in the production of the US social formation. Contrary to understandings of 9/11 and the authorization of the torture regime as a watershed moment in U.S. history “destroying the soul of America,”[x] the carceral security or pacification practices documented in the Senate Torture Report and their underpinning racial-sexual grammars of legitimate violence and suffering have played a fundamental role in the making of the US state and nation since the early days of settlement.[xi] The CIA Detention and Interrogation program[xii] targeting Muslimified subjects and populations was not only shaped by the gendered racial-sexual grammars of Orientalism, but – as has been less explored in IR[xiii] – is informed also by grammars of anti-Blackness, the capture and enslavement of Africans and the concomitant production of the figure of the Black body as the site of enslaveability and openness to gratuitous violence.[xiv]