Hot on Elke’s heels comes the news of the world’s latest doctor. Nick Srnicek, PhD. Awarded for his original thesis Representing Complexity: The Material Construction of World Politics, examined by Professors Iver Neumann and Alex Preda. A certain mastery thus attained.

Technology

Assessing Ernst Jünger: Prophet, Mystic, Accelerationist

Following on from the two previous posts (here and here), this final entry will conclude the story of Ernst Jünger’s intellectual trajectory from exalted warrior-poet to withdrawn mystic. I will then propose a brief assessment of Jünger’s legacy and contemporary relevance to our present concerns, notably to a putative political accelerationism. You can find here the full academic article on Ernst Jünger and the problem of nihilism that I published in 2016.

We pick up our story with the entry of Germany into the Second World War and Jünger’s new conscription into military service. Now aged 44, his experience of the war would however be quite different from the one that had so decisively shaped him as a young man. Following the successful French campaign, he would spend most of the war in an administrative posting in Paris where he assiduously frequented the literary and artistic circles, meeting collaborationist figures like Pierre Drieu La Rochelle and Louis-Ferdinand Céline but also Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau. As during the first war, Jünger kept a diary that would eventually be published in 1948 under the title of Strahlungen (“Radiations”). However we encounter within it a markedly different tone, reflective of the different circumstances in which he found himself but also indicative of a retreat from the ideas he had espoused up to the early 1930s. Devoid of much enthusiasm for the war, his writings appear at times almost indifferent to the wider drama playing itself out across Europe but become progressively more somber as the fate of Germany darkens, reports of atrocities in the East filter through, and his eldest son is killed in Italy.[1] Already looking ahead to the end of the conflict, Jünger also worked during the war on an essay called The Peace that proposed a vision of a united federal Europe and was circulated among the internal opposition to Hitler in the Wehrmacht. Several of these figures would be subsequently involved in the failed attempt on the Führer’s life in July 1944, a plot Jünger was seemingly aware of but took no direct part in.

The end of the war would nevertheless see Jünger being called to account for his inter-war writings. Having refused to submit to denazification, he would find himself barred from publishing for four years and he returned to live in the German countryside where he would reside until the end of his life. His remarkable longevity would grant him the opportunity for an abundant literary production, penning novels, essays and diaries ranging from science-fiction and magical realism to early ecological thinking and reflections on his multiple experiences with psychedelics. I will however restrict myself here to discussing Jünger’s immediate post-war writings since we find within them a clear statement of both the continuities and breaks with his prior thinking. Of particular importance is the text that he originally composed in 1950 on the occasion of the Festschrift for Martin Heidegger’s sixtieth birthday, Über die Linie (“Over the Line”).

Ernst Jünger on Total Mobilisation in the Age of the Worker

You can find here the full academic article on Ernst Jünger and the problem of nihilism that I published in 2016.

In this post, I will examine Ernst Jünger’s interwar writings, particularly as he moved from his recollections and reflections on the Great War (see earlier post) to a more ambitious analysis of the social and political turmoil that ensued. Sharpening his central problematique of nihilism and its overcoming, he would see in the commotions of his time the sign that the timorous bourgeois liberal societies of the nineteenth century were about to be swept away by a new technological age of total societal mobilisation and armed conflict. Anticipating and heralding the advent of the totalitarian regimes that were germinating as he wrote, the obvious points of convergence between these writings and fascist ideology have unsurprisingly made them Jünger’s most controversial. As objectionable as his political views were in their own right, Jünger was nonetheless never a National Socialist, spurning the advances made to him by the Party and having little truck with its “blood and soil” creed. He did however develop keen insights into the historical escalation of war and accompanying demands of total mobilisation alongside a withering critique of liberal societies’ preeminent concern with security and comfort.

Demobilised in 1923, Jünger spent the next three years studying zoology and developing a life-long passion for entomology (he reputedly amassed a collection of 40,000 beetles, even giving his name to a species he is credited with discovering). During those years, he also read philosophy, particularly the works of Nietzsche and Spengler. Departing from the university in 1926, Jünger then began a period of intense writing for nationalist publications and participation in the circles of the Conservative Revolutionary movement, becoming notably close to Ernst Niekisch, the central ideologist of National-Bolshevism. To enter into a detailed consideration of the ideological content of such seemingly paradoxical constellations would take us too far from our central object but it is nonetheless useful to remind ourselves of the ideological complexity and fluidity of Weimar Germany that are all too often repressed when we view the period from a post-WWII standpoint. Jünger’s independent streak also meant his associations ranged more widely than most, frequenting during this time left-wing writers such as Bertolt Brecht, Erich Mühsam, and Ernst Toller. It is within this eclectic milieu and the context of generalised crisis that his political thought was formed, leading to the publication of a series of essays in the first few years of the 1930s. Fascinated by the social and cultural effects of photography, Jünger also put together several collections of photobooks from which I have drawn the images that accompany this post.[1]

Ernst Jünger and the Search for Meaning on the Industrial Battlefield

This is the first in a series of posts on the German war veteran and author Ernst Jünger that draw on research I have presented at seminars at the University of Cambridge, University of East Anglia and University of Sussex over the last year or so. [Edit: The follow-up posts can now be found here and here]. You can find here the full academic article on Ernst Jünger and the problem of nihilism that I published in 2016.

A complex and controversial character, Ernst Jünger is mostly known today for the vivid autobiographical account of life in the trenches of the Great War he penned in Storm of Steel, one of the defining literary works produced by its veterans. Alongside its unapologetic celebration of war, it contains an unflinching, at times clinical, description of the unprecedented destruction wrought by the advent of modern industrial war. As we approach the centenary of the First World War, the text has lost none of its evocative power and is likely to remain a lasting document of the soldierly experience.

Jünger’s subsequent writings, published throughout a long life that ended in 1998 at the ripe old age of 102, are however far less well known in the English-speaking world and many of them remain untranslated to this day. And yet I want to argue that, as problematic a figure as he is, the trajectory of Jünger’s thought and work is worthy of our attention in that it crystallises in a particularly stark and vivid fashion some of the tensions and internecine struggles of the twentieth century. Jünger liked to refer to himself as a seismograph registering the underlying tectonic shifts that prefigured the tremors of his age and in the often exalted and rapturous form that took his writings they can indeed be read as a wilful exacerbation of contemporaneous trends, his failings as much his own as that of his times.

Jünger wrestled in particular with the problem of meaning and human agency in a world increasingly dominated by technology and instrumental rationality that appeared to reach their paroxysm in total war. Inheriting his philosophical outlook from Nietzsche, he understood the problem of the age to be that of nihilism, of the devaluation of all values and the increasing inability to posit any goals towards which life should tend after the ‘death of God.’ He came to view the domination of technique as central to the growth of nihilism, a proposition that appears in an inchoate but nonetheless suggestive form in Nietzsche’s own writings. This Nietzschean perspective would so come to dominate Jünger’s outlook and work that Martin Heidegger would not hesitate to dub him ‘the only genuine continuer of Nietzsche.’[1]

What We Talked About At ISA: The God Complex – Biopolitical Ethics

The paper I presented at the ISA is part of a larger project in which I look at the ways in which ethics, in the context of certain political practices, is saturated with biopolitical rationalities. The (re)surfacing and framing of hitherto morally prohibited practices – torture, extraordinary rendition, extrajudicial assassinations – as justifiable, legitimate and even necessary acts of violence, paired with rapidly advancing and increasingly autonomous military technologies that facilitate these practices, has opened new dimensions and demands for considering just what kind of ethics is used to justify these violent modalities. I’m specifically frustrated by the emerging narrative of the use of drones for targeted killing practices in the interminable fight against terror as a ‘wise’ and ‘ethical’ weapon of warfare. The prevalence of utility, instrumentality and necessity in this consideration of ethics strikes me as dubious and worthy of a closer look. This keeps leading me again and again to the perhaps foolhardy, but inevitable question: what, actually, IS ethics? And more specifically: what is ethics in a biopolitically informed socio-political (post)modern context? My quest for an answer begins with the growing divergence in scholarship and philosophical inquiry of the ethicality of ethics, or meta-ethics on one hand, and practical conceptions of ethics, applied ethics, on the other.

It has been noted by philosophers and scholars across geographical and disciplinary divides, that, in recent years, there has been a growing focus in philosophical and political thought on the application of moral and ethical principles rather than the “ethicality” of ethics itself. This trend is particularly widespread in Anglo-American philosophy, and manifests itself in the striking surge of applied ethics as a subfield of ethics, which considers the chief role of ethics to be that of providing a practical guide for moral agents, based on rational analysis, scientific inquiry and technological expertise. In other words, considerations of ethics have become preoccupied with establishing practicalities and ways of application. While the practical side of ethics should, of course, not be dismissed, the domineering focus on ethics’ practicality over considerations of meta-ethics, or the ethicality of ethics, occludes any deeper engagement with what ethics actually is, how moral content is established and how we can understand ethics in modernity as something beyond a mere set of context specific norms and legal regulations, as something other than laws and codes. To make sense of this preoccupation with ethics’ practicalities, it is worthwhile to consider how ethics might, in fact, be determined by the characteristics of a specific form of society. This brings me back to the biopolitical rationalities with which (post)modern societies are infused. Continue reading

What We Talked About At ISA: Cognitive Assemblages

What follows is the text of my presentation for a roundtable discussion on the use of assemblage thinking for International Relations at ISA in early April.

In this short presentation I want to try and demonstrate some of the qualities assemblage thinking brings with it, and I’ll attempt to do so by showing how it can develop the notion of epistemic communities. First, and most importantly, what I will call ‘cognitive assemblages’ builds on epistemic communities by emphasising the material means to produce, record, and distribute knowledge. I’ll focus on this aspect and try to show what this means for understanding knowledge production in world politics. From there, since this is a roundtable, I’ll try and raise some open questions that I think assemblage thinking highlights about the nature of agency. Third and finally, I want to raise another open question about how to develop assemblage theory and ask whether it remains parasitic on other discourses.

Throughout this, I’ll follow recent work on the concept and take ‘epistemic communities’ to mean more than simply a group of scientists.[1] Instead the term invokes any group that seeks to construct and transmit knowledge, and to influence politics (though not necessarily policy) via their expertise in knowledge. The value of this move is that it recognises the necessity of constructing knowledge in all areas of international politics – this process of producing knowledge isn’t limited solely to highly technical areas, but is instead utterly ubiquitous.

1 / Materiality

Constructivism has, of course, emphasised this more general process as well, highlighting the ways in which identities, norms, interests, and knowledge are a matter of psychological ideas and social forces. In Emanuel Adler’s exemplary words, knowledge for IR “means not only information that people carry in their heads, but also, and primarily, the intersubjective background or context of expectations, dispositions, and language that gives meaning to material reality”.[2] Knowledge here is both mental, inside the head, and social, distributed via communication. The problem with this formulation of what knowledge is, is that decades of research in science and technology studies, and in cognitive science, have shown this to be an impartial view of the nature of knowledge. Instead, knowledge is comprised of a heterogeneous set of materials, only a small portion of which are in fact identifiably ‘social’ or ‘in our heads’. It’s precisely this heterogeneity – and more specifically, the materiality of knowledge – that assemblage thinking focuses our attention on.

Knowledge is inseparable from measuring instruments, from data collection tools, from computer models and physical models, from archives, from databases and from all the material means we use to communicate research findings. In a rather persuasive article, Bruno Latour argues that what separates pre-scientific minds from scientific minds isn’t anything to do with a change inside of our heads.[3] There was no sudden advance in brainpower that made 17th century humans more scientific than 15th century humans, and as philosophy of science has shown, there’s no clear scientific method that we simply started to follow. Instead, Latour argues the shift was in the production and circulation of various new technologies which enabled our rather limited cognitive abilities to become more regimented and to see at a glance a much wider array of facts and theories. The printing press is the most obvious example here, but also the production of rationalised geometrical perspectives and new means of circulating knowledge – all of this contributed to the processes of standardisation, comparison, and categorisation that are essential to the scientific project. Therefore, what changed between the pre-scientific to the scientific was the materiality of knowledge, not our minds. And it’s assemblage thinking which focuses our attention on this aspect, emphasising that any social formation is always a collection of material and immaterial elements.

In this sense, questions about the divide between the material and the ideational can be recognised as false problems. The ideational is always material, and the constructivist is also a materialist.

Marshalling the Real: War and Simulation

This post was originally given as a talk at the Urbanomic event Simulation, Exercise, Operations held in Oxford on the 11th July 2012. Thanks to Robin Mackay for the transcription of the talk that served as a basis for the present version.

Upon reflecting on the meaning of simulation and the role it occupies in war, it strikes me that it is possible to distinguish between two distinct, if perhaps complementary, significations. There is a first signification which refers back to an older understanding of simulation and is a more etymologically faithful meaning of simulation in terms of deception, in terms of pretence, illusion, and false appearance that refers us back to the classical idea of the simulacrum as formulated by Plato. This conception of simulation invokes the notion of surface resemblance – a simulation is something that appears to be what in fact it is not. The history of the visual arts naturally provides us with numerous examples of such simulations, among others through the styles of trompe l’oeil and photorealism. Simulation here references the idea of a surface representation which may present a superficial resemblance to its object but which possesses no ontological depth. In the military context, this kind of simulation corresponds to the decoy, for example the inflatable tanks of the Second World War that may resemble tanks from a distance but which beyond that do not capture anything about what a tank actually is and how it works. Related to this is the correlated notion of dissimulation where the exercise is there not so much the representation of something that is not but the concealing of something that is, camouflage being here the obvious military referent.

Notwithstanding the significance of such practices, there is also a more contemporary meaning of simulation that will be the main object of the present post. This is a conception that is tied into the history of computing, although it does predate it, and which suggests the imitation of processes, situations and systems through the modelling of the internal characteristics and dynamics of that system and the formalisation of the constituent variables. With it comes a claim – not a claim, obviously, that we should take uncritically – to capturing some depth to whatever is being simulated, rather than simply its surface. In fact, the simulated representation might not be verisimilar and replicate our immediate phenomenological perception; it might for example merely take the form of data points on a computer printout. One common definition of a simulation that is used by computer modellers is that of “an experiment performed on a model” and indeed the concept of the model is key here because this is what distinguishes the first sense of the simulation from the second. Implicit in this second understanding of simulation is the notion of a model as a set of interrelated propositions that purport to capture the internal dynamics and behaviour of a given system. Assumptions are made about the system and mathematical algorithms and relationships are derived to describe these assumptions. These together constitute a model that purports to reveal how the system works, the operation of which can then be tested through simulation exercises with the purpose of such experiments being to better apprehend the patterns of behaviour of the system and eventually evaluate optimal conditions and variable settings for the operation of the system.

American Vignettes (I): Totalitarian Undercurrents

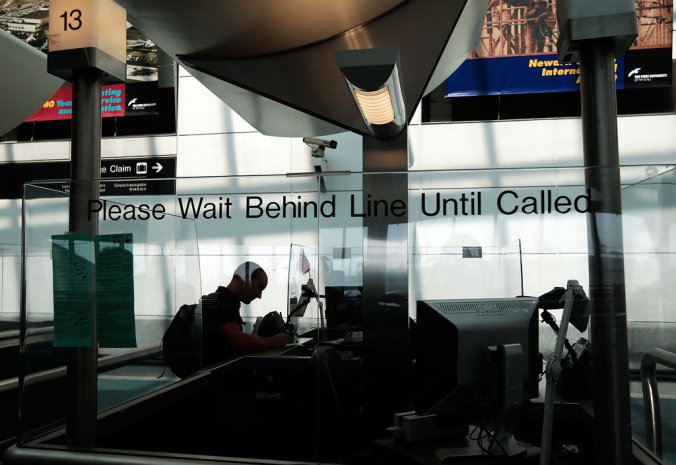

The airport is a totalitarian space; sometimes the truth is hyperbolic.

You re-enter the United States, land of your birth, as part of the stream of arriving passengers. It is an everyday experience. You leave the airplane slowly, on stiff limbs, trickling with the mass of travellers into Newark airport.

The imperatives are issued as soon as you enter the terminal building. No smoking. No cell phones. Stand in line. Fill in your declaration form. Foreigner here. Citizen there. Wait behind the red line till you are called. The armed immigration officer checks your papers, holding the power to pronounce your worthiness to enter this sanctified space.

With the imperatives come the questions. Where are you coming from? Where are you going? As if the answers are clear. As if these are simple questions. The man with the gun, holding your passport, asks, “Where are you flying next?” But he already knows and he answers for you, “Chicago, on Friday.” This is a test.

“What were you doing in London?” You answer but the officer is not interested, he looks at you with an unarticulated accusation, why would you leave your homeland? Your suspect status is confirmed when he asks, “How long are you staying?” Until you please the armed man with your answers everyone is a foreigner no matter where they were born. Continue reading

Open Access: HEFCE, REF2020 and the Threat to Academic Freedom

This is the text of a document prepared by Meera and me on Article Processing Charges as currently understood and the serious risks we think they pose to academic freedom and funding, broadly understood (previous discussed by several contributors to our open access series). It is also available as a pdf, and we encourage academics to think carefully about the issues foregrounded, and to act accordingly.

Summary

- The Government is pushing academic publishing to a ‘pay-to-say’ model in order to achieve open access to publicly funded research

- This ‘gold’ route to open access, which levies Article Processing Charges (as proposed in the Finch Report and taken up by RCUK and HEFCE) poses a major problem for academics in the UK:

- It threatens academic freedom through pressures on institutions to distribute scarce APC resources and to judge work by standards other than peer review

- It threatens research funding by diverting existing funds into paying for publications (and private journal profits) rather than into research

- It increases academic inequality both across and within institutions, by linking prestige in research and publishing to the capacity to pay APCs, rather than to academic qualities

- It threatens academic control of research outputs by allowing for commercial uses without author consent

- In response, academics should:

- Practice and lobby for ‘green’ open access of all post-peer reviewed work within journals and institutions

- Lobby against proposed restrictions on REF2020 and against compliance pressure for ‘gold’ open access

- Demand clear policies from Universities around open access funds

- Ensure institutional resources are not unnecessarily spent on APCs

- Protect the integrity of scholarly journals by rejecting the pressure for ‘pay-to-say’ publishing

Open Access: Rushing Implementation

Many academics have been ardent supporters of the open access principle (that peer-reviewed academic work should be freely available and easily accessible to anyone), and were excited when the Government made steps to advance it. However, it has become clear that the implementation of this policy via REF2020 will have very serious negative consequences for all academic authors and institutions, unless authors and institutions themselves start to take action and make their voices heard. It is critical that academics understand what is happening and lobby our pro-VCs of Research, our VCs and Universities UK to defend both academic freedom and open access.

The timescale for action and decision-making is now incredibly short. Several policies, including that of the Government and of RCUK were declared immediately with the release of the Finch Report, totally accepting its views without wider consultation. HEFCE is going to open and close a very quick consultation period early in 2013 in order to issue guidance ahead of REF2020. Some universities have been given until March 2013 to determine what to do with open access funds that they were given in November. And it was only on 29 November 2012 that the first indications from HEFCE were given as to their intentions, at the Academy of Social Sciences (ACSS) conference on Implementing Finch. The timetable for finalising the details of this complex policy is thus extremely short and does not allow for adequate discussion of its serious consequences. Despite this, academics can still play an important role in resisting the threats posed.

So, What is Happening?

In summary, academic journals are being moved from a ‘pay-to-read’ model to a ‘pay-to-say’ model.

One Size Fits All?: Social Science and Open Access

The third post in our small series on open access, publication shifts on the horizon and how it all matters to IR and social science, this time by David Mainwaring (Pablo’s post was first, then Colin Wight’s, and following David came Nivi Manchanda, Nathan Coombs and our own Meera). David is a Senior Editor at SAGE with responsibility for journals in politics and international studies. So he oversees journals like Millennium and European Journal of International Relations amongst others (which is how we know him), and can thus offer a close reading of movements within the academic publishing industry. Images by Pablo.

The third post in our small series on open access, publication shifts on the horizon and how it all matters to IR and social science, this time by David Mainwaring (Pablo’s post was first, then Colin Wight’s, and following David came Nivi Manchanda, Nathan Coombs and our own Meera). David is a Senior Editor at SAGE with responsibility for journals in politics and international studies. So he oversees journals like Millennium and European Journal of International Relations amongst others (which is how we know him), and can thus offer a close reading of movements within the academic publishing industry. Images by Pablo.

Open Access is the talk of the academic town. The removal of barriers to the online access and re-use of scholarly research is being driven by a cluster of technological, financial, moral and commercial imperatives, and the message from governments and funding agencies is clear: the future is open. What is much less clear is exactly what sort of open future social scientists would benefit from, let alone what steps need to be taken in order to transition away from the existing arrangements of scholarly communication and validation. Here the conversation is in its relative infancy, characterised at this point by a great deal of curiosity, anticipation, confusion, and the shock of the new. What it needs to move towards is a recognition and coordinated response to the fact that although social science may share the same open access goal as the STEM disciplines, the motivations for travelling down that path are not identical, and the context – especially in terms of research funding – is significantly different. The roundtable discussion at the Millennium conference at the LSE on 20th October was an attempt to explore these issues specifically from an IR perspective; further such events (such as those being run by the AcSS and LSE this autumn) are to be warmly welcomed as a means of building broader understanding of the issues among social scientists and facilitating strategic thinking.

Social Science and the Open Access Debate

The long-running debate about how scholarly research communication should be funded and transmitted has been, and remains, a discussion conducted primarily by those working in STEM. Most of the blogosphere’s best-known voices on open access, the likes of Mike Taylor, Michael Eisen, Peter Murray-Rust, Björn Brembs, Cameron Neylon, Kent Anderson, Stephen Curry and Tim Gowers, have backgrounds in STEM research or publishing. (Notable exceptions are the philosopher Peter Suber, who heads the Harvard Open Access Project, and self-archiving advocate Stevan Harnad, a cognitive scientist). To dip into the often heated debates on open access can leave you with the strong impression that, despite the occasional nod to social science and the humanities, the frame of reference is proper, rigorous, natural scientific research, the kind carried out in a laboratory that leads to medical advances and the development of new technologies.

By and large social scientists – and arts and humanities scholars, to whom many of the points raised in this piece apply equally – have had a back seat in this conversation, and the development of open access awareness and capabilities has been slow. Many leading social science journals continue to be distributed in print form due to subscriber demand well over a decade after the launch of their online editions. The American Political Science Association’s 2009 book Publishing Political Science devotes just two out of over 250 pages to open access, and fewer than 10% of the nearly 13,000 signatories of the ‘Cost of Knowledge‘ boycott of Elsevier were social scientists, despite the company’s position as one of the world’s leading publishers of social science journals. That’s not to say that there is nothing going on: the Social Science Research Network has acted as a site for open paper sharing since 1994; there are active ‘open’ movements in disciplines including IR and economics; and the Directory of Open Access Journals lists more than 1,600 social science titles. To date, however, very few of the latter have been able to break into the higher echelons of profile or reputation within their fields.

Social Science and Open Access Mandates

Over the last eighteen months a series of events, including George Monbiot’s polemic in The Guardian and the defeat in the US of the Research Works Act, stirred for the first time a significant consciousness among social scientists about open access. This awareness increased dramatically – in the UK at least – with the publication in June 2012 of the final report of a committee set up by the Government to examine access to published research findings. Continue reading