Saif Gaddafi (PhD, LSE, 2008) has lost a lot of friends recently. Even Mariah Carey is embarrassed by him now. The institution to which I have some personal and professional attachment is implicated in a number of intellectual crimes and misdemeanours, as may be a swathe of research on democracy itself. Investigations are under way, by bodies both official and unofficial. All of this now feels faintly old-hat (how much has happened in the last month?), even rather distasteful given the high politics and national destinies currently in the balance. So let the defence be pre-emptive: the academy has political uses, and those with some stake in it need feel no shame in discussing that. If crises are to be opportunities, let us at least attempt to respond to them with clarity and coherence. After all, our efforts are much more likely to matter here than in self-serving postures as the shapers of global destiny.

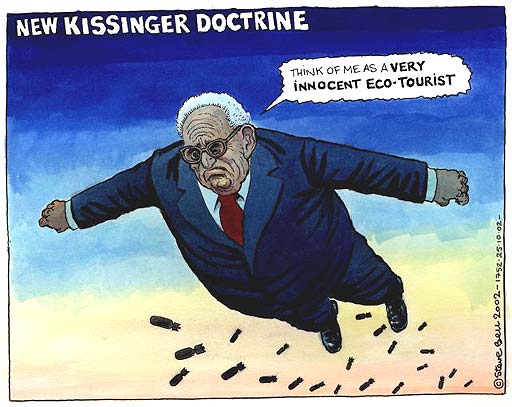

Saif’s academic predicament is both a substantive issue in its own right and a symptom. As substance, there is now a conversation of sorts around complicity and blame. Over the last weeks, David Held has appealed for calm and attempted a fuller justification of his mentorship (Held was not the thesis supervisor and Saif was not even a research student in his Department at the time, although he, um, “met with him every two or three months, sometimes more frequently, as I would with any PhD student who came to me for advice”). Most fundamentally, it was not naivety but a cautious realism based on material evidence that led a pre-eminent theorist of democracy to enter into what we could not unreasonably call ‘constructive engagement’. [1]

Held characterises the resistance of Fred Halliday to all this as reflecting his view that “in essence, [Saif] was always just a Gaddafi”, which of course makes him sound like someone in thrall to a geneticist theory of dictatorship. The actual objection was somewhat more measured, and, if only ‘in retrospect’, entirely astute: