In which Patricia Owens responds to our four commentaries (on patriarchy, colonial counterinsurgency, biopolitics and social theory) on her Economy of Force.

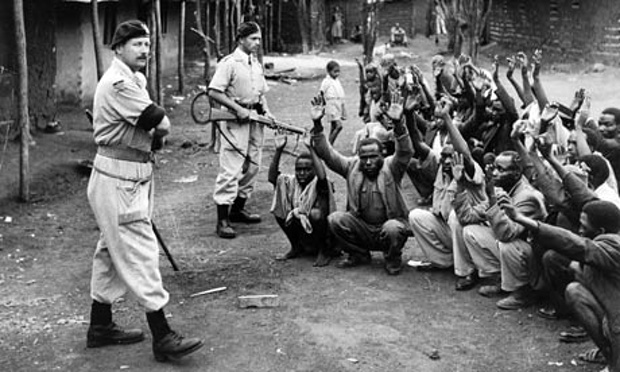

I’m extremely grateful to Pablo K, Elke Schwarz, Jairus Grove, and Andrew Davenport for their serious engagements with Economy of Force. As noted in the original post, the book is a new history and theory of counterinsurgency with what I think are significant implications for social, political and international thought. It is based on a study of late-colonial British military campaigns in Malaya and Kenya; the US war on Vietnam; and US-led campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq against the background of the high colonial wars in the American Philippines and nineteenth-century French campaigns in Tonkin, Morocco and Algeria. Probably the emblematic case for the book is Britain’s colonial state terror against Kenya’s Land and Freedom Army and civilians in the 1950s, a campaign that was closer to annihilation than ‘rehabilitation’. Although the so-called ‘hearts and minds’ campaign in Malaya is held up by generations of counterinsurgents as the model for emulation, the assault on Kikuyu civilians shows the real face of Britain’s late-colonial wars. It also points to some profound truths about the so-called ‘population-centric’ character of more recent campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq. Though offering new readings of some better-known counterinsurgency cases, Jairus Grove suggests that this choice perpetuates an erasure of America’s ‘Indian Wars’.

Researching Economy of Force, I certainly became aware of the general significance of these wars, including through Andrew J. Birtle’s and Laleh Khalili’s histories of counterinsurgency. However, Grove draws attention to something more relevant to Economy of Force than appreciated before: “one of the first federal bureaucracies with jurisdiction over the home and social issues”, he writes, “was created by and administered by the War Department”. Decades before the distinctly ‘social’ engineering during the Philippines campaign (1899-1902), the Bureau of Indian Affairs was administering indigenous populations on the mainland. In focusing on overseas imperial wars, Economy of Force surely neglects settler colonialism, its genocides, and how “warfare, pacification, and progressivism were an assemblage in the US context from the outset”. While the book was not centrally focussed on US state making, I’m grateful to Grove for insisting that settler colonialism is necessarily a form of counterinsurgency. To be sure, the Philippines campaign was examined not as the founding moment of American counterinsurgency, but because it was explicitly conceived by contemporaries as a form of overseas housekeeping; to problematize progressive social policy; and to challenge the effort to separate good (domestic) social engineering at home from bad social engineering (overseas). I would hesitate to wholly assimilate the Progressive Era (1890s-1920s) into earlier Indian Wars, though its ‘social reforms’ shaped indigenous administration. But these are quibbles. Grove is right that I have neglected something of significance in the ‘historical trajectory from Thanksgiving to Waziristan’. I hope to be able to rectify this in future work.