For a blog apparently devoted to global politics, we have so far rather neglected its voguish scandals and intrigues. Disciplinary exposure therapy has evidently done its work, particularly where the amorphous theory-cum-policy-manual of Realism is concerned. After all, what could be more mutually disappointing than a lengthy online discourse on the neo-neo ‘debate’ or its ilk? So much somnabulatory exegesis.

For a blog apparently devoted to global politics, we have so far rather neglected its voguish scandals and intrigues. Disciplinary exposure therapy has evidently done its work, particularly where the amorphous theory-cum-policy-manual of Realism is concerned. After all, what could be more mutually disappointing than a lengthy online discourse on the neo-neo ‘debate’ or its ilk? So much somnabulatory exegesis.

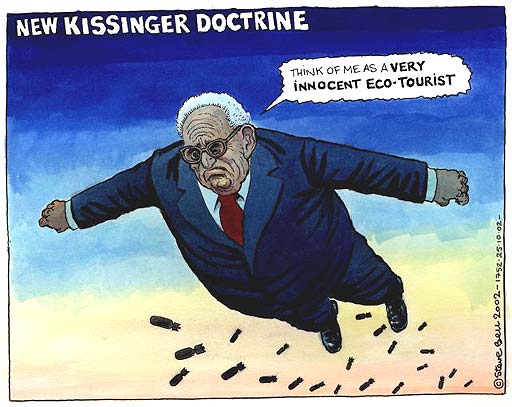

That said, last month’s fracas over ‘criminal psychopath’ and one-time ‘elegant wit’ Dr Henry A. Kissinger deserves a mention. In new releases from the Nixon tapes, his fawning jingoism in the name of some clear-cut national interest rather caught the eye:

The emigration of Jews from the Soviet Union is not an objective of American foreign policy…And if they put Jews into gas chambers in the Soviet Union, it is not an American concern. Maybe a humanitarian concern.

Bushite polemicist Michael Gerson took the opportunity to indict Realism, denouncing its shallow moral compass in favour of a vision of more righteous foreign policy (neo-conservative manifest destiny branch). Stephen Walt responded, pointing out that Kissinger is not the delegated representative of Realists, that many who self-describe as such opposed both the Vietnam and Iraq wars, and that hand-wringing by culpable members of the Bush administration over the human costs of foreign policy is straight-up hypocrisy. Henry Farrell at Crooked Timber rightly stressed that this was besides the point, since what makes Kissinger Realist in the relevant sense is his instrumentalist attitude to the lives of others and the over-riding importance of material power in his world view. Along the way, he also provided a particularly apt description of this particular peace-prize winning carpet-bomber as in thrall to “a scholar’s fantasy of Metternich, in which cynicism, duplicity, and clandestine brutality were not foreign policy tools so much as a demonstration of one’s ‘seriousness’ as a statesman“. Nice. Enter Christopher Hitchens, spraying invective like it was the old days and usefully dismantling the apologetics now apparently emanating from several quarters [1].

Naturally, the seriousness of Kissinger’s servile indifference is as nothing next to his actual and extensive crimes, if legal language can be made to fit the special character of his achievements. And one can hardly credit that the good doctor’s snivelling before the anti-Semitism of Richard Milhouse Nixon should matter half as much as his responsibility for the deaths visited on Kien Hoa or the euphemistic and not-so-euphemistic barbeques served up as part of operations ‘Breakfast’, ‘Lunch’, ‘Dinner’, etcetera. Continue reading