Anyone who followed the controversy over the fictitious Gay Girl in Damascus blog, created by Edinburgh-based US graduate student Tom MacMaster writing as Amina Arraf, might have despaired of the prospects of subalterns speaking for themselves. Female, lesbian, Arab, and an anti-Assad protester, MacMaster’s Amina quickly became a posterchild of the Arab Spring for a wide swath of the liberal media and activist blogosphere. For those cognizant of contemporary critiques of homonationalism against the backdrop of pervasive homophobia, Amina’s dispatches from the frontline seemed a perfect embodiment of left liberal fantasies about the possibilities for progressive sexual politics in a time of revolution. Yet if critics such as Joseph Massad have been accused of dismissing subjects who don’t conform to their theoretical predilections, the Amina hoax gestured at an opposite, if no less insidious, temptation: that of desperately seeking subjects who confirmed theoretical utopia.

Feminism

Love, Sex, Money and Meaning

UPDATE (8 September 2014): Megan originally wrote this as a guest post, but is now with us more permanently.

This post is based on stories about sex, love, tourism and identity relayed in Cuba in 2010, and is (loosely) based on, and at times excerpted from, an article of the same name just published in Alternatives: Global, Local, Political. All names, many locations, and some additional identifying details have been changed in accordance with the interviewees’ wishes.

Yakelín comes to the Hotel St. John nearly every day around two o’clock in the afternoon. Most days, Jean-Claude is already there, ensconced on the terrace with a glass of dark rum, chatting amiably with the staff, or pensively smoking a cigar as he waits. When she arrives, she kisses him discreetly before settling down for a drink on the terrace. The hotel is rather unassuming, but it sits just steps from the busy east end of Calle 23, known as La Rampa, and blocks from the historic University of Havana, and as such Hotel St. John has become a haven for tourists and foreign students who come here for strong coffee and cold beer. After an hour or so, Yakelín and Jean-Claude walk away together, hand in hand.

This same routine has been going on for more than two years now, since the day that Yakelín first met Jean-Claude, walking along Calle 23 with a friend. She was 21 years old, living in a small flat with her mother, father, brother, two sisters, aunt, uncle, two cousins and her grandmother. After spending her teenage years at a boarding school in the countryside, she had elected not to continue to university and was back in Havana with her family. Like so many others, her family worked hard to make ends meet, and Yakelín was looking for ways to lighten the burden. Not long after they met, Jean-Claude made her a proposition.

He suggested that, since I was en la lucha [struggling to get by], you know, he suggested that I no longer be in the streets [looking for leads on work, food, clothes] and that he was going to help me resolver mis problemas [solve my problems]. And since then, he’s my boyfriend.

Jean-Claude is married, but Yakelín says that in spite of that they have a “formal relationship” – she lives in a comfortable casa particular, for which he pays, and they spend every afternoon together. As a retiree, Claude lives more or less permanently in Cuba, leaving only to attend to his affairs in France and returning laden with gifts including clothing, jewellery, and even a television. He provides her with spending money and helps to support her family as well. She says she loves the independence he has given her, even though she readily acknowledges the implied contradiction – she has found her freedom in total dependence on him. Yakelín has no official work at present, because she feels that the meagre salary is simply not worth the trouble.

Symptoms Worse Than Death

The “daughter of India” died in a hospital in Singapore yesterday, causing shockwaves around the globe and placing India on the verge of a violent implosion. Whilst rape had become a matter that women were told that they had to contend with in their everyday lives, that they must make it safer for themselves by not being alone after dark, by not dressing provocatively, and by not drinking or acting in a manner that is ‘lewd’ and ‘unladylike’, especially in North India, something about this case has led to a national uprising of unprecedented proportions. People have taken to the streets, New Year eves’ parties have turned into mass commemoration events, and the Internet is positively ablaze with news, blogs, and posts about this nameless woman whose impact on Indian politics today cannot be exaggerated.

India has had the distinction of being labelled the worst country in the world for women and Delhi is often called India’s ‘rape capital’, so perhaps it is not surprising that a 23-year old woman was gang-raped on a bus by six men on the way home after watching The Life of Pi with her boyfriend. It is perhaps also not surprising that the rape was brutal, that a metal rod was shoved into her vagina, that the men took turns at “having a go” and finally got rid of both her and her male friend by throwing them out of the window of the moving bus. What is surprising, however, is the reaction. Why has an event that may even be classified as mundane garnered so much attention and prominence?

Many on the so-called Left in India have proclaimed that the case has been given such importance only because the woman was (ostensibly) middle-class and it is always a shock when it happens to “us”, not least when it happens in a manner this horrific. Most of the mobilized youth claim that this was the last straw in what has been a devastatingly protracted chain of brutalities against women. The cynics argue that reactions such as these are tokenistic gesture that will change nothing but help those protesting come together in a moment of collective catharsis, share in a feeling of shame and sorrow not unlike that experienced when Pakistan defeats India in a cricket match. For me, the answer to the question posed above is ultimately immaterial. Yes, the woman was not a Dalit or Adivasi, and crimes against the poor in India vastly exceed those against the rich. And yes, the injustices perpetrated against the rich, powerful or established have historically been at the forefront of media reporting and government agendas, as was most blatantly obvious in the case of the Mumbai attacks in 2008. And indeed, it is unlikely that there will be any overwhelming change in either attitudes or policy towards women in the immediate aftermath of this insurrection.

In light of this, should we just lull ourselves into a state of callous complacency and churn out platitudes about the state of our society? Those who want to are welcome to squander away both hope and perspective. For those who recognise that the path to any significant change is thorny but may yet render itself navigable, some acknowledgement of the conditions that have made gender-based violence possible and continue to make it possible, even run-of-the-mill, is in order. An awareness of how we ourselves, albeit unwittingly, reproduce these conditions and help engender systemic violence that is both symbolic and ‘real’ is also urgently needed. We must be cognisant of the fact that India is a deeply conservative society and the ‘opening-up’ of the economy since 1991 has witnessed a patriarchal backlash in the face of rising inequity, the collapse of the extended family and the disappearance of any social welfare. Those who have placed the blame singularly on “Indian men” and our “backward culture” – and who think revenge in the form of capital punishment and castration is the only solution – fail to take into account how deeply embedded they are in this patriarchal order and how readily they are partaking of a discourse that is both misogynistic and short-sighted.

The calls for castration are symptomatic of an acutely phallocentric order – where a man’s ‘masculinity’ is considered his greatest pride, and the source of this masculinity is none other than his reproductive organs. Similarly, the widespread proclamation that “rape is a crime worse than murder” and must be punished accordingly has a patently sinister side to it. Is a woman (or man for that matter) who has been raped not entitled to a life? Is she “worse than murdered”? Is it the “defilement”, the snatching away the “honour” and “purity” of a woman that so bothers us? It is worth remembering that the woman who died yesterday, who the Indian government in yet another meaningless and flippant gesture has called a “martyr” and “Delhi’s braveheart”, desperately wanted to live. She had been “violated” by six men in an ordeal that lasted over an hour, was on life-support, but not, in her own opinion, worse than dead. She was only (worse than) dead after she died.

The protests in Delhi and around India contain within themselves a latent emancipatory potential. But in order for this to amount to anything, even something as pedestrian as allowing women to negotiate public spaces in Delhi without constant threat of harassment, we must think about how our subjectivity as women, men, and citizens is (re)produced. This is the only way we can build up some resistance to the “common-sense” we are invariably brought up with. We need to start problematising the taken for granted assumptions that our heteronormative order inflicts upon us everyday, most importantly the implicit belief that women are “less equal” than men. The contours and manifestations of this tacit hierarchy may be different in the West from those in the global South, but the substance remains largely the same. As always, the words of anthropologist Barbara Diane Miller resonate deeply: “We must not forget that human gender hierarchies are one of the most persistent, pervasive and pernicious forms of inequality”. Change will not come easy.

(Im)Possibly Queer International Feminisms

We’ve previously mentioned the 2013 International Feminist Journal of Politics annual conference – on the topic of ‘(Im)Possibly Queer International Feminisms’. It turns out that there is extra reason to trumpet its existence: our very own Rahul Rao (author these excellent posts) will be one of the conference keynotes, alongside such others as Lisa Duggan (NYU), Jon Binnie (Manchester Met), Vivienne Jabri (Kings), V. Spike Peterson (Arizona), Laura Sjoberg (Florida), Rosalind Galt, Akshay Khanna, and Louiza Odysseos (all Sussex)! A lot of other exciting papers will be on display, some of which I’ll be associated with. And there’s also a pre-conference workshop on Queer, Feminist and Social Media Praxis. Clearly not an occasion to miss.

We’ve previously mentioned the 2013 International Feminist Journal of Politics annual conference – on the topic of ‘(Im)Possibly Queer International Feminisms’. It turns out that there is extra reason to trumpet its existence: our very own Rahul Rao (author these excellent posts) will be one of the conference keynotes, alongside such others as Lisa Duggan (NYU), Jon Binnie (Manchester Met), Vivienne Jabri (Kings), V. Spike Peterson (Arizona), Laura Sjoberg (Florida), Rosalind Galt, Akshay Khanna, and Louiza Odysseos (all Sussex)! A lot of other exciting papers will be on display, some of which I’ll be associated with. And there’s also a pre-conference workshop on Queer, Feminist and Social Media Praxis. Clearly not an occasion to miss.

The full call is as follows:

(Im)possibly Queer International Feminisms

The 2nd Annual IFjP Conference

May 17-19, 2013

University of Sussex, Brighton, England

The aim of this conference is to serve as a forum for developing and discussing papers that IFjP hopes to publish. These can be on the conference theme or on any other feminist IR-related questions.

Feminists taught us that the personal is political. International Relations feminists taught us that the personal is international. And contemporary Queer Scholars are teaching us that the international is queer. While sometimes considered in isolation, these insights are connected in complex and sometimes contradictory ways. This conference seeks to bring together scholars and practitioners to critically consider the limits and possibilities of thinking, doing, and being in relation to various assemblages composed of queer(s), international(s), and feminism(s).

Questions we hope to consider include: Who or what is/are (im)possibly queer, (im)possibly international, (im)possibly feminist, separately and in combination? What makes assemblages of queer(s), international(s) and feminism(s) possible or impossible? Are such assemblages desirable – for whom and for what reasons? What might these assemblages make possible or impossible, especially for the theory and practice of global politics?

We are interested in papers and panels that explore these questions through theoretical and/or practical perspectives, be they interdisciplinary or located within the discipline of International Relations.

Sub-themes include (Im)Possibly Queer/International/Feminist:

- Heteronormativities/Homonormativities/Homonationalisms

- Embodiments/Occupations/Economies/Circulations

- Temporalities/‘Successes’/‘Failures’

- Emotions/Desires/Psycho-socialities

- Technologies/Methodologies/Knowledges/Epistemologies

- Spaces/Places/Borders/(Trans)positionings

- States/Sovereignties/Subjectivities

- Crossings/Migrations/Trans(gressions)

- (In)Securities

We invite submissions for individual papers or pre-constituted panels on any topic pertaining to the conference theme and sub-themes. We also welcome papers and panels that consider any other feminist IR-related questions.

Any inquiries should be addressed to the conference coordinator, Joanna Wood, at cait@sussex.ac.uk

Abstracts should be no more than 250 words.

Deadline for submissions: January 31, 2013

We will, however, confirm acceptance of submissions before the deadline if we receive abstracts early. Early submission is therefore recommended.

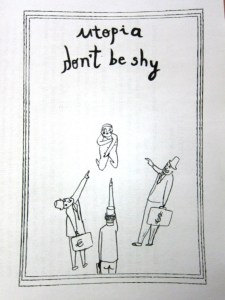

This Courage Called Utopia

(wild bells) A warm Disordered welcome to Wanda Vrasti, who previously guested on the topic of the neoliberal tourist-citizen imaginary, and now joins the collective permanently. And glad we are to have her. Her academic writings thus far include Volunteer Tourism in the Global South: Giving Back in Neoliberal Times (which came out with the Routledge Interventions series a few months ago), ‘The Strange Case of Ethnography in International Relations’ (which caused its own debate), ‘”Caring” Capitalism and the Duplicity of Critique’, and most recently ‘Universal But Not Truly “Global”: Governmentality, Economic Liberalism and the International’.

It’s often been said that this is not only a socio-economic crisis of systemic proportions, but also a crisis of the imagination. And how could this be otherwise? Decades of being told There Is No Alternative, that liberal capitalism is the only rational way of organizing society, has atrophied our ability to imagine social forms of life that defy the bottom line. Yet positive affirmations of another world do exist here and there, in neighbourhood assemblies, community organizations, art collectives and collective practices, the Occupy camps… It is only difficult to tell what exactly the notion of progress is that ties these disparate small-is-beautiful alternatives together: What type of utopias can we imagine today? And how do concrete representations or prefigurations of utopia incite transformative action?

First thing one has to notice about utopia is its paradoxical position: grave anxiety about having lost sight of utopia (see Jameson’s famous quote: “it has become easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”) meets great scepticism about all efforts to represent utopia. The so-called “Jewish tradition of utopianism,” featuring Adorno, Bloch, and later on Jameson, for instance, welcomes utopianism as an immanent critique of the dominant order, but warns against the authoritarian tendencies inherent in concrete representations of utopia. Excessively detailed pictures of fulfilment or positive affirmations of radiance reek of “bourgeois comfort.” With one sweep, these luminaries rid utopianism of utopia, reducing it to a solipsistic exercise of wishing another world were possible without the faintest suggestion of what that world might look like.

But doing away with the positive dimension of utopia, treating utopia only as a negative impulse is to lose the specificity of utopia, namely, its distinctive affective value. The merit of concrete representations of utopia, no matter how imperfect or implausible, is to allow us to become emotionally and corporeally invested in the promise of a better future. As zones of sentience, utopias rouse the desire for another world that might seem ridiculous or illusory when set against the present, but which is indispensable for turning radical politics into something more than just a thought exercise. Even a classic like “Workers of the World Unite!” has an undeniable erotic (embodied) quality to it, which, if denied, banishes politics to the space of boredom and bureaucracy. It is one thing to tell people that another world is possible and another entirely to let them experience this, for however shortly.

Most concrete representations and prefigurations of utopia from the past half century or so have been of the anti-authoritarian sort. Continue reading

Female Terrain Systems: Engagement Officers, Militarism, and Lady Flows

One of the more interesting interventions made at Friday’s Gender, Militarism and Violence roundtable came from Vron Ware on the topic of a photo exhibit about the British Army’s Female Engagement Officers. The exhibit is funded by the Poppy Appeal, which was itself subject to some debate as a sentimental memorialism allocating funds in the service of a imperial-nostalgic self-image. The pictures, collected by a female former RAF Sergeant, are presumably understood by military and civilian leaders to be a significant public relations resource in illustrating the flexibility, equity and decentness of Anglo-American-Western ‘involvement’ in Afghanistan. Manifestations of cultural sensitivity, postfeminist integration and armies as state-building reconciliation services. And yet someone decided, both on the Army website and Twitter account, that the best image to lead with was that of knickers on a washing line. A puerile social media engagement.

The rest of the images, and the media coverage of them, focus heavily on assorted ‘personal’ issues experienced by the women. Gaze on their beauty products! See how they control their lustrous hair! Peak in on their need for mementos of home! Marks of difference indeed, although none of the coverage I have seen broaches the possibility that men too might stash deodorant in their tents, or manage their body hair to maintain professional standards, or display reminders of loved ones waiting at home. Instead, as any gender-sensitive observer might expect, the specially femininity of these troops displaces all other dimensions of war/peace/development/security (an impression encouraged by some of the subjects themselves). The BBC even recently juxtaposed the death of a female army medic with an image of another woman coming out of the shower tent. A soft voyeurism on military women as leaky bodies and as somehow out of place. But not just that. The juvenilia comes packaged together with the idea of the Female Engagement Officers as crucial to a kind of military effectiveness:

Captain Crossly told the London Evening Standard that one of the highlights of the tour was ‘seeing the absolute fascination of women in the compound when I removed my helmet and protective glasses to speak to them in their own language’.

She added: ‘Women are known throughout the world to bring people together, to focus on family and community. Just by being female, even in military uniform, you are seen to promote such things and are therefore more accepted.’

Lieutenant French said: ‘The photographs demonstrate the more feminine traits of female soldiers can be used as a strength on operations.’

The Cursory Pedant: War Rape, the Human Security Report and the Calculation of Violence

“Cursory and pedantic”. So says IntLawGrrls’ Fionnuala Ní Aoláin of the just released Human Security Report 2012 (hereafter HSR). You may recall the team behind the HSR from their last intervention, which upset the applecart over the estimate of 5.4 million excess deaths in Congo (DRC) since 1998 and which also claimed a six decade decline in global organised violence. The target this time round is a series of putative myths about wartime sexual violence (those myths being: that extreme sexual violence is the norm in conflict; that sexual violence in conflict is increasing; that strategic rape is the most common – and growing – form of sexual violence in conflict; that domestic sexual violence isn’t an issue; and that only males perpetrate rape and only females are raped), each of which the authors claim to overturn through a more rigorous approach to available evidence. Along the way an account is also given of the source of such myths, which is said to be NGO and international agency funding needs, which lead them to highlight the worst cases and so to perpetuate a commonsense view of war rape that is “both partial and misleading”.

Megan MacKenzie isn’t impressed either, especially by HSR’s take on those who currently study sexual violence:

[HSR’s view is] insulting because it assumes that those who work on sexual violence – like me – those who have sat in a room of women, where over 75% of the women have experienced rape – as I have – listening to story after story of rape, forced marriage, and raising children born as a result of rape, it assumes that we are thinking about what would make the best headline, not what are the facts, and not what would help the survivors of sexual violence.

Laura Shepherd (who like Ní Aoláin and Megan has written at some length on these issues) took a slightly different approach: “It makes not one jot of difference whether rates of [incidents of conflict-related sexual violence] are increasing, decreasing or holding entirely steady: as long as there are still incidents of war rape then the issue demands serious scholarly attention rather than soundbites”. Activists are concerned less by what the report says than by how it will be interpreted and the effects this will have on victims and survivors of rape (the danger, in Megan’s words, that “painting rape as random is another means to detach it from politics”). By contrast, Laura Seay (who has previously addressed similar issues in relation to Congo) is very supportive: “it’s hard to find grounds on which to dispute most of these claims. The evidence is solid”. Andrew Mack (who directs the HSR) similarly replied that the data supports HSR’s claims and that, despite criticisms, it had been checked rigorously.

So what is going on here?

Queerly Global Politics: Some Events

Normal blogging service soon to be resumed. In the meantime, two gender and world politics events of note. First, on Friday 2 November, a roundtable on gender, militarisation and violence at LSE, featuring Cynthia Enloe, Aaron Belkin, Kim Hutchings,and others. It will be excellent. Second, the call for papers for the 2nd International Feminist Journal of Politics is out. The conference is a way away (17-19 May 2013 at the University of Sussex), but early paper/panel submissions are encouraged. Details below the model military aesthetic.

(Im)possibly Queer International Feminisms

Feminists taught us that the personal is political. International Relations feminists taught us that the personal is international. And contemporary Queer Scholars are teaching us that the international is queer. While sometimes considered in isolation, these insights are connected in complex and sometimes contradictory ways. This conference seeks to bring together scholars and practitioners to critically consider the limits and possibilities of thinking, doing, and being in relation to various assemblages composed of queer(s), international(s), and feminism(s).

Questions we hope to consider include: Who or what is/are (im)possibly queer, (im)possibly international, (im)possibly feminist, separately and in combination? What makes assemblages of queer(s), international(s) and feminism(s) possible or impossible? Are such assemblages desirable – for whom and for what reasons? What might these assemblages make possible or impossible, especially for the theory and practice of global politics?

We are interested in papers and panels that explore these questions through theoretical and/or practical perspectives, be they interdisciplinary or located within the discipline of International Relations. Sub-themes include (Im)Possibly Queer/International/Feminist:

- Heteronormativities/Homonormativities/Homonationalisms

- Embodiments/Occupations/Economies/Circulations

- Temporalities/‘Successes’/‘Failures’

- Emotions/Desires/Psycho-socialities

- Technologies/Methodologies/Knowledges/Epistemologies

- Spaces/Places/Borders/(Trans)positionings

- States/Sovereignties/Subjectivities — Crossings/Migrations/Trans(gressions)

- (In)Securities

We invite submissions for individual papers or pre-constituted panels on any topic pertaining to the conference theme and sub-themes. We also welcome papers and panels that consider any other feminist IR-related questions. Send abstracts (250 words) to: Joanna Wood (j.c.wood [at] sussex.ac.uk)

Deadline for submissions: 31 January 2013

A Magical Anti-Rape Secretion

Todd Akin (R-MO) says that doctors told him that women can’t get pregnant from rape. The doctor in question was presumably Onesipherous W. Bartley, whose 1815 A Treaties on Forensic Medicine or Medical Jurisprudence explained that conception:

must depend on the exciting passion that predominates; to this effect the oestrum/veneris must be excited to such a degree as to produce that mutual orgasm which is essentially necessary to impregnation; if any desponding or depressing passion presides, this will not be accomplished. (via)

At least we know how up to date a certain kind of Republican is on the medical literature. Aaron ‘zunguzungu’ Bady offers a less generous, but surely more astute, diagnosis:

The thing about a chucklehead like Rep. Akins is that he doesn’t actually care whether or not women have a magical anti-rape secretion in their body that makes conception less likely. That’s the whole point: his right not to have to worry about it. If you look at his entire statement, for example, you’ll notice that his foray into weird science was tangential to his main point, which was, simply, punish the criminal not the child. And this is more or less orthodox GOP doctrine, which has the hammer of law enforcement and looks for nails: solve the problem of rape by hammering the criminal, and make abortion into a crime, so you can hammer that too. But this simple-minded approach stumbles when it runs into the problem of the rape-victim: how to have empathy for the victim (because “victim’s rights” is a central pillar of the law and order approach) while also criminalizing her if she gets an abortion? How to insulate her choice to get an abortion from the contingency she did not control, and could not have chosen?

As many have pointed out, then, the first imperative is to make it her choice, and therefore her fault. But there’s still he cognitive dissonance of a rape victim forced to have the child of a rapist, something that doesn’t sit at all easily in the mind of a right wing family-and-police; she’s still a problem, and a thorny one. And so, a simple answer, for a simple mind: she does not exist. He argues that the rape victim who is impregnated is a fantasy of people who want to make the whole thing complicated and difficult, with their “ethics” and “problems,” and so he invents a “doctors told me” story to make it make sense, to explain how what seems complicated is actually simple. But the fact that he’s just making shit up, that women’s body’s aren’t Nature’s Own Anti-Rape Kit, is irrelevant; when you believe in the super-sufficiency of simple laws (and in The Law), problem-cases just become nails to be hammered down or ignored, while “facts” are nothing more that the warrant for doing so.

Feminist Notes, part I

By including what violates women under civil and human rights law, the meaning of “citizen” and “human” begins to have a woman’s face. As women’s actual conditions are recognized as inhuman, those conditions are being changed by requiring that they meet a standard of citizenship and humanity that previously did not apply because they were women. In other words, women both change the standard as we come under it and change the reality it governs by having it applied to us. This democratic process describes not only the common law when it works but also a cardinal tenet of feminist analysis: women are entitled to access to things as they are and also to change them into something worth our having.

Thus women are transforming the definition of equality not by making ourselves the same as men, entitled to violate and silence, or by reifying women’s so-called differences, but by insisting that equal citizenship must encompass what women need to be human, including a right not be sexually violated and silenced. This was done in the Bosnian case by recognizing ethnic particularity, not by denying it. Adapting the words of the philosopher Richard Rorty, we are making the word “woman” a “name of a way of being human.” We are challenging and changing the process of knowing and the practice of power at the same time.

-Catharine MacKinnon, “Postmodernism and Human Rights,” Are Women Human?