We’re on a roll now. On Friday, Omar became the fourth of us to ascend the greased pole of academic accreditation since we began cultivating this little corner of the internet. Forever more to be known as Dr El-Khairy, his burgeoning cultural insurgency notwithstanding. The work in question? American Statecraft for a Global Digital Age: Warfare, Diplomacy and Culture in a Segregated World. And who said it was good enough? Faisal Devji and Eyal Weizman, actually. So there. And I have promises in writing that he will be telling us more about it all real soon.

Academe

Materialism and World Politics conference

Materialism and World Politics

20-22 October, 2012

LSE, London, UK

Registration is now open here for anyone who wants to attend.

Scheduled Speakers:

Keynote: The ontology of global politics

William Connolly (Johns Hopkins University)

Opening Panel: What does materialism mean for world politics today?

John Protevi (Louisiana State University)

More TBC

Closing Panel: Agency and structure in a complex world

Colin Wight (University of Sydney)

Erika Cudworth (University of East London)

Stephen Hobden (University of East London)

Diana Coole (Birkbeck, University of London)

ANT/STS Workshop keynote:

Andrew Barry (University of Oxford)

ANT/STS Workshop roundtable:

Iver Neumann (LSE)

Mats Fridlund (University of Gothenburg)

Alberto Toscano (Goldsmiths, University of London)

More TBC

*******

The annual conference for volume 41 of Millennium: Journal of International Studies will take place on 20-22 October, 2012 at the London School of Economics and Political Science. This includes 2 days of panels and keynotes on the weekend, and a special Monday workshop on actor-network theory (ANT), science and technology studies (STS), and alternative methodologies. Space for the latter is limited though, so let Millennium know of your interest in attending it as soon as possible.

The theme of this year’s conference is on the topic of materialism in world politics. In contrast to the dominant discourses of neorealism, neoliberalism and constructivism, the materialist position asks critical questions about rational actors, agency in a physical world, the role of affect in decision-making, the biopolitical shaping of bodies, the perils and promises of material technology, the resurgence of historical materialism, and the looming environmental catastrophe. A large number of critical writers in International Relations have been discussing these topics for some time, yet the common materialist basis to them has gone unacknowledged. The purpose of this conference will be to solidify this important shift and to push its critical edges further. Against the disembodied understanding of International Relations put forth by mainstream theories, this conference will recognize the significance of material factors for world politics.

It’s Really Kicking Off In Quebec

Despite some news coverage and discussions on Twitter, we’ve seen little on the continuing educational and political crisis in Quebec. Hence, a guest post from our friend and colleague Philippe Fournier. Philippe teaches political thought and International Relations at the Université de Montréal and the Université du Québec à Montréal. He has published research on Foucault and International Relations, Governmentality in the contemporary United States and Violence and Responsibility. He is currently working on the government of security in the US and on the theoretical conflation of sovereign power and government in Foucault. His other research interests include critical cultural theory and political economy.

Despite some news coverage and discussions on Twitter, we’ve seen little on the continuing educational and political crisis in Quebec. Hence, a guest post from our friend and colleague Philippe Fournier. Philippe teaches political thought and International Relations at the Université de Montréal and the Université du Québec à Montréal. He has published research on Foucault and International Relations, Governmentality in the contemporary United States and Violence and Responsibility. He is currently working on the government of security in the US and on the theoretical conflation of sovereign power and government in Foucault. His other research interests include critical cultural theory and political economy.

A little background info and some thoughts on the student crisis in Quebec, which has been going on for 101 days now and shows no signs of waning in the face of the government’s disturbing intransigence. The recent adoption of Bill 78, which circumvents the right to protest without prior notice and gives the police the right to change a demonstration’s itinerary, among other things, has shocked and angered many Quebecers and made the news worldwide. On Tuesday May 22, over 250 000 people expressed their discontent with the current government and it was quite a sight.

Ever since the ‘quiet revolution’ in the early 1960s, which saw the institution of important social provisions and the attribution of several socio-economic entitlements to the francophone majority, Quebec has been holding fast to its social-democratic heritage. Jean Charest’s liberal party, in power since 2003, is determined to fight off the modern-day antichrist of debt and rationalise state activity. The Charest government’s attack on hard fought social entitlements, including accessible post-secondary education (Quebec has the lowest tuition fees in Canada), has been going steady since 2003 but has intensified since 2008. Quebecers were told that it was no longer reasonable to expect affordable public services and that it was high time that we join the pay as you go party.

What is at play in this conflict is no less than the fate of social-democratic expectations in Quebec. These expectations are actively discouraged and discredited by the current political elite. The demands for a tuition freeze by sizeable portions of Quebec’s students are considered unreasonable in many quarters, and seen as a plane expression of bad faith and overindulgence by a majority of Canadians, seemingly stuck in a Stephen Harper induced stupor. The words ‘pragmatic’, ‘realistic’ and ‘rational’ have been duly appropriated by the partisans of deregulation, free-enterprise and individual responsibility. Any suggestions that the latter orientations are based on an ideological choice are ridiculed; they simply express a sounder and more logical way to manage society.

Up to now, there seemed to be a dour resignation to the decimation of our social programs. This young generation of Quebecers, which many had touted as completely apathetic and apolitical, has taken a resolute stand against restricting access to a public good, against the further commodification of knowledge and against the uncompromising law and order approach of an arrogant and irresponsible government. Those that have taken to the streets day after day and sacrificed their terms and put their professional lives on hold for the students that will come after them, have shown extraordinary resilience and bravery. It came as a surprise to many, because they did it on their own, with little or no help from their political science professors, who have long abandoned critical thinking for functionalist replications of reality sanctioned by government money.

Mapping the (In)Visibility of Gender in Politics and International Relations

Do elite institutions teach the global politics of gender and sexuality on any scale or in any depth? Emma Foster, Peter Kerr, Anthony Hopkins, Christopher Byrne and Linda Åhäll (all of Birmingham, at least when they did the research) have an Early View piece up at The British Journal of Politics and International Relations addressing just this question. Surveying the course content of the 16 top Politics and IR Departments in the UK (‘top’ meaning either in the top 10 in student satisfaction scores or in REF scores), they give some empirical confirmation of what many of us might have known anecdotally:

Our findings…show, in our view quite strikingly, that few political science and international relations departments offer extensive or in-depth coverage of gender and sexuality issues. As a result, many political science and international relations undergraduates merely experience a brief introduction to ‘feminism’ as their only encounter with key debates over gender inequalities and sexual identity.

Of 629 modules in IR and Politics identified across those Departments, only 9 existing full modules related to gender or sexuality (increasing to 12 if Aberystwyth’s ‘forthcoming’ courses are included). That’s 1.4%. Only an estimated 8.9% of all surveyed modules offer at least one week on feminism/gender as part of their wider sweep. The study also shows up some noteworthy cases where there is Departmental expertise but no teaching provision. Warwick and Oxford both have seven staff listing gender/feminism as a core research interest, but Warwick hosts only one gender-related module and Oxford none. Although the paper does not pursue this in great detail, the suggestion is that the relative paucity of courses is not a result of absent expertise, since the progress of feminist and gender studies has been sufficient that all Departments surveyed (with the exception of de Montfort) have staff members with a gender interest. Indeed, on the average of these 16 elite institutions, there are some 3.9 gender specialists in each one (although numbers are always, of course, shifting).

The overall picture, then, is of some progress (perhaps surprisingly limited) in getting gender (but not sexuality) included as the spectral “week on feminism”, presumably primarily in theoretical survey modules. But this vague and introductory inclusion is not supported by more concentrated work either theoretically (as in a module on different perspectives on gender) or empirically (as in an issue-by-issue survey of gender in global politics). Although Foster et al. do not map changes in Faculty composition, this appears to be happening at the same time as gender and feminist academics are increasing in strength within IR.

As is to be expected, this leaves a number of issues unaddressed. Continue reading

What We Talked About At ISA 2012: How Music Brings Meaning to Politics

At this year’s ISA conference, I presented on the panel ‘The Social Technologies of Protest’, with George Lawson, Eric Selbin, Robbie Shilliam and our discussant Patrick Jackson. The full text of the draft paper is available here. Thanks go to the panel and audience for some fascinating questions and discussions.

Music is a world within itself

With a language we all understand

With an equal opportunity

For all to sing, dance and clap their hands

But just because a record has a groove

Don’t make it in the groove

But you can tell right away at letter A

When the people start to move

– ‘Sir Duke’, Stevie Wonder, Songs in the Key of Life (1976)

Music is an old and effective technology of politics. This was highly visible in both the recent uprisings and the attempts at counter-revolution; whilst from the beginning Tunisian activists sang their national anthem in the street in anti-regime protest, Assad blasted the Syrian anthem into the cities as a reminder of his position. Rappers and older musicians shared platforms in Tahrir Square, and DJs parodically remixed Gaddafi’s final public speeches into technotronic nonsense. Whilst not all political music is sung of course, songs and the act of singing are particularly powerful in political situations as means and symbols of mobilisation and unification. Moreover, songs tend to linger in the brain.

But there are at least two ways of thinking about the relationship between politics and music. The question which is perhaps most often asked and answered is: how, when and where is music political? So, why did the Tunisian protesters sing the national anthem in front of the courthouse, how did music support the anti-apartheid struggle, and why did the Haitian revolutionaries sing the Marseillaise? How did the musical character of these expressions facilitate a particular kind of political act? Lots of excellent writers, both scholarly and otherwise, have turned their attentions to the nature of political music, and especially protest music, in a variety of times and places.

However, the question that I want to focus on mainly here though is slightly different: how, when and where is politics musical? This question was stimulated by the general observation that when we try to make sense of politics, we often use metaphors related to music. A common phrase is that a political statement or value ‘struck a chord’ with an audience, or that protesters are ‘banging a drum’. Politicians may or may not be ‘in tune’ with publics, and relations may be ‘harmonious’ or not. Coups will be ‘orchestrated’.

Perhaps surprisingly, in moving from vernacular to scholarly modes of understanding politics, the metaphors of music are no less important. In fact, in some cases they seem to be more important. The genre-defining work of the historical sociologist Charles Tilly in the study of contentious politics is a revealing and fascinating case in point.

What We Talked About At ISA: Researching Sexuality in ‘Difficult’ Contexts

In September 2009, Ugandan Parliamentarian David Bahati introduced a draft ‘Anti Homosexuality Bill’ that proposed enhancing existing punishments for homosexual conduct in the Ugandan Penal Code, introducing new ‘related offences’ including ‘aiding and abetting’ homosexuality, ‘conspiracy to engage’ in homosexuality, the ‘promotion of homosexuality’, or ‘failure to disclose the offence’ of homosexuality to authorities within 24 hours, and mandating the death penalty for a select class of offences categorized as ‘aggravated homosexuality’. The bill remained bottled up in parliamentary committees for the duration of the 8th Parliament, thanks in large part to a sophisticated local campaign that sought to bring international pressure to bear on the government of President Yoweri Museveni, but has since been reintroduced in the current 9th Parliament and therefore remains a live concern. In August 2010, I travelled to Uganda to interview a range of actors associated with ongoing debates over sexuality in the country. Rather than commenting on the urgent and pressing substantive concerns at issue in these debates, at an ISA panel entitled ‘Researching sexuality in difficult contexts’, I chose to reflect on some of the methodological dilemmas I encountered in the field, for which my training in international relations had left me unprepared. Emboldened by recent ISA panels on storytelling and auto-ethnography (and utterly bored by what passes for mainstream IR), these reflections take the form of excerpts from my diary (italicized), interspersed with the more censorious, academic voice that I trotted out at ISA. (I make no apology for not writing about the more ‘serious’ issues at stake—on this occasion—because it occurs to me that where sexuality is concerned, the pursuit of fun can raise deadly serious questions, making distinctions between the trivial and the serious difficult to sustain.)

Uganda, August 2010: I am here to do interviews and I spend most of my day setting them up, preparing for them, travelling to or from them, or conducting them. The rest of the time I hang out, people watch, trying to piece together a picture of how life outside heteronormativity survives in a climate that seems—on the surface at least—as inhospitable as Uganda is supposed to be. On Friday, Al (name changed, and this account provided with permission) invited me to a strip-tease. This was going to be a straight strip-tease, but one that some of the gay men went to so that they could watch the straight men getting off on watching the women strip. It sounded convoluted, but unmissable. Plus, I’d never been to a straight strip-tease, so it seemed important to plug this gaping orifice in my sexual history. We entered a dimly lit hall and took seats at the back in a group near the bar. I think I was the only brown man there. There was also one white man in the whole place, in our group. He had evidently been to the place before, and because he came with the same motivations as Al, he had been traumatized on a previous occasion by the way the women flocked to him (money?). So Al was instructed to tell the emcee (a short guy dressed in a white track suit) to make sure that the women didn’t come to our corner. The real attraction, from the point of view of the gay guys, was that the women sometimes got the straight guys to get on stage and strip. Al told the emcee to do his best to encourage this possibility. Call it Straight Guy for the Queer Eye. I was impressed by the brazenness with which Al communicated all this to the emcee. As for the show, let’s just say it took the ‘tease’ out of strip-tease. The first woman (girl? all the performers looked like they were in their 30s, but they could have been younger and prematurely aged by their work) danced to some vaguely familiar Western pop number. She was followed by another woman with bigger hips. Somebody in the group, setting himself up as my informant, tells me that she is ‘a real African woman’. She danced to Shania Twain’s ‘From this Moment On’ (a song I played to my last (and final, I think) girlfriend on the first day I met her, after a year-long correspondence). Just when Shania reached the second verse, the woman dropped her panties. None of the performers took off their bras. ‘African men aren’t interested in breasts’, my self-appointed informant intones. The next half-hour is a blur of female anatomy. So here I am, in a country that people have been calling ‘conservative’ and that American evangelist Rick Warren has decided is ripe for transformation into the world’s first ‘purpose driven’ nation, looking at more naked women in ten minutes than I have seen in ten years, to the soundtrack of my failed romantic history.

Open Access, Harvard Delight Edition

An extraordinary and delightful communiqué from Harvard on journal pricing has surfaced (early reactions here and here and here). It was actually issued almost a week back, but the Twitter hive mind (or my corner of it) appears only now to have noticed (h/t to JamieSW for that). The contents are pretty extraordinary, even too good to be true. The preamble is brutal about the current state of the journal system, observing that Harvard spent almost $3.75 million last year on bundled journal provision from some publishers (10% of all collection costs and 20% of all periodical costs for 2010); that “profit margins of 35% and more suggest that the prices we must pay do not solely result from an increasing supply of new articles”; that “[t]he Library has never received anything close to full reimbursement for these expenditures from overhead collected by the University on grant and research funds”; and that “[i]t is untenable for contracts with at least two major providers to continue on the basis identical with past agreements. Costs are now prohibitive” (I’m guessing one provider at least is Elsevier).

An extraordinary and delightful communiqué from Harvard on journal pricing has surfaced (early reactions here and here and here). It was actually issued almost a week back, but the Twitter hive mind (or my corner of it) appears only now to have noticed (h/t to JamieSW for that). The contents are pretty extraordinary, even too good to be true. The preamble is brutal about the current state of the journal system, observing that Harvard spent almost $3.75 million last year on bundled journal provision from some publishers (10% of all collection costs and 20% of all periodical costs for 2010); that “profit margins of 35% and more suggest that the prices we must pay do not solely result from an increasing supply of new articles”; that “[t]he Library has never received anything close to full reimbursement for these expenditures from overhead collected by the University on grant and research funds”; and that “[i]t is untenable for contracts with at least two major providers to continue on the basis identical with past agreements. Costs are now prohibitive” (I’m guessing one provider at least is Elsevier).

Then some options-cum-recommendations for Faculty are laid out:

1. Make sure that all of your own papers are accessible by submitting them to DASH in accordance with the faculty-initiated open-access policies.

2. Consider submitting articles to open-access journals, or to ones that have reasonable, sustainable subscription costs; move prestige to open access.

3. If on the editorial board of a journal involved, determine if it can be published as open access material, or independently from publishers that practice pricing described above. If not, consider resigning.

4. Contact professional organizations to raise these issues.

5. Encourage professional associations to take control of scholarly literature in their field or shift the management of their e-journals to library-friendly organizations.

6. Encourage colleagues to consider and to discuss these or other options.

7. Sign contracts that unbundle subscriptions and concentrate on higher-use journals.

8. Move journals to a sustainable pay per use system.

9. Insist on subscription contracts in which the terms can be made public.

Note in particular point 3. Harvard is asking its academics to seriously consider resigning from major journals if substantive good-faith moves are not made towards open access or “sustainable subscription costs” (read: a major reversal of current practice). As previously suggested, only serious insurgencies within major centres of academic prestige will undo the private stranglehold on knowledge-in-common. On those grounds, I’m tempted to giddy excitement. The question, of course, is which other major institutions (and which serious academic figures) will have the solidarity and good sense to follow this example. As a rallying point, social sciences and social theory need some version of The Cost Of Knowledge manifesto that spans the entire issue of journals and knowledge production. At the very least, we now have a new rhetorical device: open access is good enough for Harvard: why isn’t it good enough for you?

What We Talked About At ISA: From #occupyirtheory to #OpenIR?

A write up of my comments at the #occupyirtheory event in San Diego. The event itself was both hope-filled and occasionally frustrating, not least for the small group of walk-outs, apparently ‘political’ ‘scientists’ lacking in any conception of what it actually means to engage in the political (note: this bothered me especially, but was a rather minor irritation in the grander scheme of things). Despite the late hour, there were between 40 and 60 people there throughout, and a number of very positive things have come of it. It looks like there’ll be some gathering at BISA/ISA to discuss further, and we’re pitching something for the Millennium conference on some of the themes addressed below, and there will of course be ISA 2013 too. In the meantime, there’s the Facebook group, the blog, and a mailing list. The term OpenIR is owed to Kathryn Fisher, and seems to several of us to be a better umbrella term for the many things we want to address in the discipline and the academy. I also just want to give a public shout-out to Nick, Wanda, Robbie and Meera for doing so much on this.

The #occupy practice/meme has antecedents. Physical manifestations of a ‘public’, horizontalism, prefigurative politics and more can be traced in all sorts of histories. One such lineage is the foreshadowing of Zucotti Park in recent struggles over education. Take the slogan in March 2010 over privatisation at the University of California, which was ‘STRIKE / OCCUPY / TAKEOVER’. Or Middlesex, where students resisting the dismantling of the Philosophy Department in that same year unfurled a banner during their occupation, one that proclaimed: ‘THE UNIVERSITY IS A FACTORY! STRIKE! OCCUPY!’.

I want briefly, then, to think about the space of the university in our discussions of #occupy. There have been rich and suggestive calls to re-politicise ourselves as academic-activists, to look again at our work and its claims, and to turn our abilities, such as they are, to projects of resistance and transformation. But we risk a displacement. When we talk of ‘the street’, or politics enacted in the reconfigured space of #occupy, or of the ‘real world’ that we must be relevant to, we already miss the university itself as that factory in which we labour. We are tempted by a view of ourselves as leaving ivory towers to do politics, instead of seeing those towers themselves as spaces of politics. As if our institutions and practices were not already part of the world.

Whether you see #occupy as transformational or nor, or whether you simply prefer a different vocabulary, I think a demand remains: a demand to politicise our own positionality. This politicisation can have many dimensions, but I want to suggestively highlight four, each being a sphere in which we should be diagnosing and transforming our own practices.

#occupyirtheory, International Studies Association (San Diego) Edition

ISA 2012 is just around the corner, and it will doubtless be as hectic and awkward and joyous as ever. Robbie and I will be appearing at an event on #occupy and its relevance for IR on Tuesday at 7 in Indigo 204 at the Hilton Bayfront. We’ll be joining Lucian Ashworth, Lara Coleman, Nicholas Kiersey and Wanda Vrasti (all chaired by Jason Weidner) for what I’m sure will be an exciting roundtable discussion. More importantly, it will be brief, with most of the session given over to a General Assembly-style discussion of what IR can learn from #occupy, what #occupy might get from IR, and how we might take the spirit and organisational form into the discipline itself (or not).

The hope is that the slightly later starting time will allow people to go both to the various Section receptions and meetings (briefly) and to come to this, whilst still leaving reasonable evening time for food and the rest. Please do get involved over at Facebook (see also the #occupyirtheory group and #occupyirtheory blog) and let interested IR-types know. Readers may also be (should also be!) interested in a recent forum from the Journal of Critical Globalisation Studies on ‘Occupy IR/IPE’, featuring Nick and Wanda (as well as Colin Wight, Michael J. Shapiro, Patrick Jackson and others), which I’ve parcelled together as a single pdf for your delectation here.

Hope to see you there!

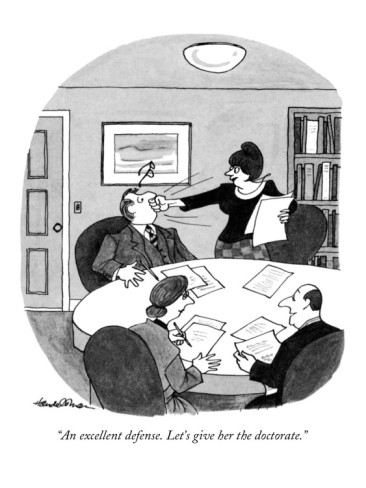

Dr Sabaratnam, I Presume?

Hot on Roberto’s heels, and the third of us to achieve doctorhood since the inception of The Disorder Of Things, our very own Meera today survived the critical questioning of Robbie Shilliam and Christopher Cramer. She is henceforth Dr Sabaratnam, certified by virtue of her thesis: Re-Thinking the Liberal Peace: Anti-Colonial Thought and Post-War Intervention in Mozambique. For the record, I’m assured that any violence inflicted was purely intellectual.