Author: Joe

Human Rights as Crisis Morality – a reply

If Anthony will forgive my presumptuousness, it seems that the crisis of human rights that worries him is that while critics have much to offer by highlighting the limitations, paradoxes, silences and aporias of human rights, they fail to offer a moral vision that can inspire or a practical politics that might make the world better. This concern goes beyond the practiced rejection of philosophising as an indulgence in the face of human misery. Anthony is concerned with the deeper problem faced by those critics who identify human rights with the global exertion of Western authority and a depoliticised vision of the individual and society under the conditions of contemporary neo-liberal capitalism. And that problem is that the process of critique itself risks overwhelming the possibility of political action for moral ends – to do good on behalf of, and in solidarity with, the “poor, downtrodden and despised”.

There’s a crude version of this critique that suggests human rights naysayers are obscurantist intellectuals, whose evasive politics demonstrate the bankrupt quietism of the contemporary left – or, as they would say back home, that they are “all hat and no cattle”. In his post Anthony is getting at something more substantive and, I think, very important, which is the difficulty of finding a critical ground for moral action in political life. If one admits the limitations and pernicious aspects of human rights as a broad set of political practices, what alternative justification can be offered for political action?

While supportive of human rights, Anthony is quite clear that the

difficulty here for human rights is that the very rhetoric of the movement, with its built in moralism and boosterism, makes it hard to consider that “human rights might be a bad thing”, or that they may not be the best – and certainly not the only – framework for considering serious problems and issues within the international system.

For this reason he respects the important role that critiques of human rights play in recognising the tendency for moral claims to be co-opted by political power, deconstructing the essentialised account of humanity, tracing the violence done to difference through universal claims and acknowledging the politics inherent in any account of justice. The key question, then, is what happens in the wake of our critical interrogation of human rights? Continue reading

A Slow Motion Moral Collapse, or, the Principle of Magic?

Belief in magic did not cease when the coarser forms of superstitious practice ceased. The principle of magic is found whenever it is hoped to get results without intelligent control of means; and also when it is supposed that means can exist and yet remain inert and inoperative. In morals and politics such expectation still prevail, and in so far the most important phases of human action are still affected by magic. We think that by feeling strongly enough about something, by wishing hard enough, we can get a desirable result, such as virtuous execution of a good resolve, or peace among nations, or good will in industry. We slur over the necessity of the cooperative action of objective conditions, and the fact that this cooperation is assured only by persistent and close study. Or, on the other hand, we fancy we can get these results by external machinery, by tools or potential means, without a corresponding functioning of human desires and capacities. Often times these two false and contradictory beliefs are combined in the same person. The man who feels that his virtues are his own personal accomplishment is likely to be also the one who thinks that by passing laws he can throw the fear of God into others and make them virtuous by edict and prohibition.

-John Dewey, Human Nature and Conduct

Racist Lies, Oslo Edition: Jihadists, Lone-Wolves, and the Far-Right

Last week (Friday 22 July), a man brought a brutal plan to its grim conclusion in Oslo and Utoeya. After years of festering in resentment and roiling with anger, he worked up the conviction to act on his beliefs. He methodically worked out how to make and plant a home-made bomb. He coldly calculated an ambush of young women and men participating in a political summer camp.

He detonated his car bomb and killed 8 people, as well as damaging the prime minister’s office and several buildings in the area. While the city reacted to the terrifying scene, this man calmly made his way to a summer camp on the island of Utoeya dressed as a policeman, armed with an automatic rifle and enough ammunition to carry out an hour-long attack on the residents of the camp. He killed 68 people before surrendering.

Lie No. 1:

As shocking as the attack in Oslo was, it was apparently less shocking than the identity of this angry and violent man. Right-wing media outlets predictably lead with the unconfirmed story that the attack was carried out by Jihadists. But even mainstream commentators and more responsible media outlets ran with the Islamic terror story without evidence and have pushed the angle even after it was revealed that the perpetrator was a white, Christian, “nationalist” from Norway.

Why did the press so quickly and thoroughly misrepresent the story? We can talk about a knee-jerk response or blame faulty reporting, but there’s a simpler and more troubling dynamic at work here. That answer is that “we” expect angry and violent men committing these type of attacks to be Muslim, non-white, non-European.

Why did the press so quickly and thoroughly misrepresent the story? We can talk about a knee-jerk response or blame faulty reporting, but there’s a simpler and more troubling dynamic at work here. That answer is that “we” expect angry and violent men committing these type of attacks to be Muslim, non-white, non-European.

Even as the true perpetrator of last Friday’s attacks was found and his own racist views made public, the media and the public struggled to accept and understand Anders Breivik because of their own entrenched racism. The hands that commit such violence are supposed to be brown hands, hands that pray to a false and violent God, hands raised in angry protests in far away countries, hands reaching out to choke white victims. Our image of violence reveals the violence of our images.

The blithe accusation of Muslim extremists and the immediate belief that the attacks in Oslo must have been perpetrated by Al-Qaeda, or some other shadowy network, reveal how deeply racist narratives are embedded in “our” understanding of the world.

Pragmatist Notes, part III

In spite of the fact that diversity of political forms rather than uniformity is the rule, belief in the state as an archetypal entity persists in political philosophy and science. Much dialectical ingenuity has been expended in construction of an essence or intrinsic nature in virtue of which any particular association is entitled to have applied to it the concept of statehood. Equal ingenuity has been expended in explaining away all divergences from this morphological type, and (the favored device) in ranking states in a hierarchical order of value as they approach the defining essence. The idea that there is a model pattern which makes a state a good or true state has affected practice as well as theory. It, more than anything else, is responsible for the effort to form constitutions offhand and impose them ready-made on peoples. Unfortunately, when the falsity of this view was perceived, it was replaced by the idea that states “grow” or develop instead of being made. This “growth” did not mean simply that states alter. Growth signified an evolution through regular stages to a predetermined end because of some intrinsic nisus or principle. This theory discouraged recourse to the only method by which alterations of political forms might be directed: namely, the use of intelligence to judge consequences. Equally with the theory which it displaces, it presumed the existence of a single standard form which defines the state as the essential and true article. After a false analogy with physical science, it was asserted that only the assumption of such a uniformity of process renders a “scientific” treatment of society possible. Incidentally, the theory flattered the conceit of those nations which, being politically “advanced,” assumed that they were so near the apex of evolution as to wear the crown of statehood.

– John Dewey, The Public and Its Problems (1927)

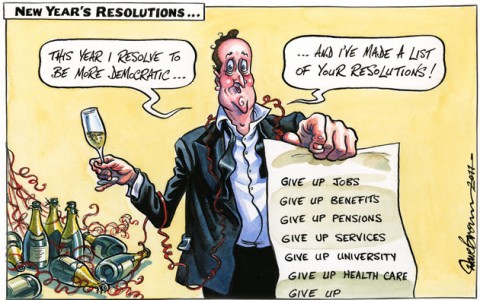

The Politics of Austerity: Emergency Economics and Debtocracy

austerity |ôˈsteritē| noun – sternness or severity of manner or attitude

It was possible, therefore, to commit a sin without knowing that you committed it, without wanting to commit it, and without being able to avoid it. Sin was not necessarily something that you did: it might be something that happened to you.

– George Orwell, “Such, Such Were the Joys”

Why what have you thought of yourself?

Is it you then that thought yourself less?

Is it you that thought the President greater than you?

Or the rich better off than you? or the educated wiser than you?

I do not affirm that what you see beyond is futile, I do not advise that you stop,

I do not say leadings you thought great are not great,

But I say that none lead to greater than these lead to.

– Walt Whitman, “A Song for Occupations,” Leaves of Grass

The Politics of Austerity – Part I

This is the first in a series of posts that look at the political implications of the ongoing global economic crisis. I begin by examining the way that crisis is being used to attack the very idea of democracy through an assertion of the political imperatives of “the market” and the violation, bending and re-writing of the law by capitalist elites. I conclude by laying out how understanding the economic crisis in political terms shapes our ability to respond to it.

In the second post I’ll look at the ethos of austerity, which justifies the pain inflicted on largely innocent people, while suggesting that an affirmative democratic response to the economic crisis must begin with its own ethos, which I suggest should be an ethos of care for the world – which can provide orientation and inspiration for political struggles seeking to address the deeper causes of our current crisis. In the third post, I turn to the structures of the economy and of politics that define the current crisis, looking at the banking crisis, the bailouts, the politics of recovery/austerity and also reflecting of the structural imperatives of capitalism that led us to crisis. This, then, leads to the question of how to respond to the politics of austerity, and of what alternative actions are available to us, which is where the fourth and final post will pick up – with an affirmation of a caring ethos that supports a radically democratic economic vision.

Emergency Economics

In a previous post I briefly highlighted Bonnie Honig’s work, Emergency Politics, to examine the way that the ethical case for austerity is made; most basically, the existence of a supreme emergency, in this case economic, justifies actions that would normally be considered unacceptable. Honig’s work looks at how the appeal to emergency is used to reassert the exceptional political power of the sovereign over and against the law, with a focus on the reassertion of sovereignty witnessed over the past ten years in response to the threat of terrorist attack in the US and Europe.

Rather than accepting the necessarily intractable conflict between the power of the sovereign and the power of the law, Honig attempts to deflate this paradox by turning her attention to the always ongoing contestation that defines democratic politics, a contest over both the content of the law and the institutional embodiment of sovereign power. She suggests, then, that attending to the ambiguities of the “people”, who are both the democratic sovereign and a diffuse multitude, as well as the political element in the law – as new laws come into being through political action – enables us to avoid thinking about emergencies as moments of exception in which the rule of law is lost to the play of political power, while also acknowledging the limits of established law in moments of profound crisis. By undermining the exceptional nature of crises and emergencies Honig alters the challenge we face when circumstances force us to make choices or carry out actions we know are harmful and wrong by asking what we (democratic publics and citizens) can do to survive an emergency with our integrity in tact.

What do we need to do to ensure our continuity as selves and/or our survival as a democracy with integrity? Our survival depends very much on how we handle ourselves in the aftermath of a wrong. We will not recover from some kinds of tragic conflict. But when faced with such situations, we must act and we must inhabit the aftermath of the situation in ways that promote our survival as a democracy.

I continue to find this a useful way to understand our current economic crisis. Appeals to austerity depend upon the exceptional state created by crisis in order to justify the pain inflicted upon masses of people and the priority given to private interests (the markets, investors and bankers) over democratic publics. So, as democratically enacted laws must bow before the sovereign power threatened by exceptional attacks, so economic justice and democratic equality must bow before the commands of market forces, of economic inevitability, in this time of crisis.

The economic version of this argument is stronger still. While the space of political contestation that remains open when we accept the framing of emergency politics is limited, it does exist in the clashing of opposing sovereigns. The prospect of a substantive alternative to neoliberal economic ideology is dim, a light flickering weakly on antiquated appeals for a return to Keynesianism or watered down triangulations of the moderate-middle that sell off dreams of a just economy bit by bit – capitalist realism in action.

Honig awakens us to an important aspects of our current crisis: that “the market” is not in fact supremely sovereign, and the move to re-establish and further neoliberal policies and push through austerity measures requires an engagement in democratic politics – albeit one that undermines the notion of the public itself and seeks to use the power of the law to subvert democracy. Recognising the current crisis in these terms not only challenges us to consider how to survive our current troubles without giving up democratic virtues, it also reinvigorates and clarifies the political challenge we face. Emergency economics – with its assertion of debtocracy over democracy – is not an inevitable response to the crisis, it is a political one that we can, and should, fight against.

What We (Should Have) Talked About at ISA: The Politics of Humanity and The Ambiguous History of Human Rights – Part III

This is the final post in a series laying out a set of interrelated arguments I presented at this year’s ISA conference. The first post looked at the nature of human rights claims, while the second considered how rethinking human rights in terms of contestation over the ambiguous meaning of humanity as a political identity affects our understanding of the history of human rights. In the final post I suggest a positive ethos, enabled by attending to human rights in terms of agonism and pluralism.

Human Rights as a Democratising Ethos

In part 1, I analysed human rights as an attempt to offer a universal moral justification of political authority. This is a perennial political question, but one which is reconfigured by talk of “human rights”, as the political identity of humanity opens up question over who is included in political community, as well as the boundaries that define such communities. The stakes of the question of human rights – offering a universal account of who is included as a rights bearing member of the political community, and the legitimate order of that community – lead to a profound anxiety over justifications. The moral reasons we have to uphold human rights should be weighty, powerful and certain – or so the logic dictates.

What emerges from this logic is an essentially legislative understanding of human rights, in which moral principles give justification for the necessary and minimal law to grant legitimacy to the universal vision of both individual and community. If this moral law is to be more than an imposition of power, a merely effective positive law, it must involve a universal moral appeal that cannot be denied in order to secure human rights as the necessary law of legitimate authority. In this regard Habermas’ defense of moral universality and human rights are indicative and sophisticated examples. (Habermas 1992, 1998)

Interrogating Democracy in World Politics

After a lengthy gestation Interrogating Democracy in World Politics is now available from Routledge. The edited volume, which Meera, Laust Schouenborg and myself put together, features a set of critical essays examining the meaning and role of democracy in world politics by top thinkers in the field. We’re obviously very excited to see our names on the front of a book and to continue exploring a topic that began as a special issue (Vol. 37, No. 3) of Millennium: Journal of International Studies back in 2009. For the moment you can preview our introduction to the book on the Routledge website to get a taste of what’s on offer.

Pragmatist Notes, part II

To be set on fire by a thought or scene is to be inspired. What is kindled must either burn itself out, turning to ashes, or must press itself out in material that changes the latter from crude metal into a refined product. Many a person is unhappy, tortured within, because he has at command no art of expressive action. What under happier conditions might be used to convert objective material into material of an intense and clear experience, seethes within in unruly turmoil which finally dies down after, perhaps, a painful inner disruption.

Persons who are conventionally set off from artists, “thinkers,” scientists, do not opperate by conscious wit and will to anything like the extent popularly supposed. They, too, press forward toward some end dimly and imprecisely prefigured, groping their way as they are lured on by the identity of an aura in which their observations and reflections swim. Only the psychology that has separated things which in reality belong together holds that scientists and philosophers think while poets and painters follow their feelings. In both, and to the same extent in the degree in which they are of comparable rank, there is emotionalized thinking, and there are feelings whose substance consists of appreciated meanings or ideas.

The psychology underlying this bifurcation was exploded in advance by William James when he pointed out that there are direct feelings of such relations as “if,” “then,” “and,” “but,” “from,” “with.” For he showed that there is no relation so comprehensive that it may not become a matter of immediate experience. Every work of art that ever existed had indeed already contradicted the theory in question. It is quite true that certain things, namely ideas, exercise a mediating function. But only a twisted and aborted logic can hold that because something is mediated, it cannot, therefore, be immediately experienced. The reverse is the case. We cannot grasp any idea, any organ of mediation, we cannot possess it in its full force, until we have felt and sensed it, as much so as if it were an odor or a color.

Whenever an idea loses its immediate felt quality, it ceases to be an idea and becomes, like an algebraic symbol, a mere stimulus to execute an operation within the need of thinking. For this reason certain trains of ideas leading to their appropriate consummation (or conclusion) are beautiful or elegant. They have an esthetic character. In reflection it is often necessary to make a distinction between matters of sense and matters of thought. But the distinction does not exist in all modes of experience. When there is genuine artistry in scientific inquiry and philosophical speculation, a thinker proceeds neither by rule nor yet blindly, but by means of meanings that exist immediately as feelings having qualitative color.

Santayana has truly remarked: “Perceptions do not remain in the mind, as would be suggested by the trite simile of the seal and the wax, passive and changeless, until time wears off their rough edges and makes them fade. No, perception falls into the brain rather as seeds into a furrowed field or even as sparks into a keg of gunpowder. Each image breeds a hundred more, sometimes slowly and subterraneously, sometimes (as when a passionate train is started) with a sudden burst of fancy.” Even in abstract processes of thought, connection with the primary motor apparatus is not entirely severed, and the motor mechanism is linked up with reservoirs of energy in the sympathetic and endocrine system. An observation, an idea flashing into the mind, starts something. The result may be a too direct discharge to be rhythmic. There may be a displace of rude undisciplined force. There may be a feebleness that allows energy to dissipate itself in idle day-dreaming. There may be too great openness of certain channels due to habits having become blind routines – when activity takes the form sometimes identified exclusively with “practical” doing. Unconscious fears of a world unfrienly to dominating desires breed inhibition of all action or confine it within familiar channels. There are multitudes of ways, varying between poles of tepid apathy and rough impatience, in which energy once aroused, fails to move in an ordered relation of accumulation, opposition, suspence and pause, toward final consummation of an experience. The latter is then inchoate, mechanical, or loose and diffuse. Such cases define, by contrast, the nature of rhythm and expression.

-John Dewey, Art as Experience

What We (Should Have) Talked About at ISA: The Politics of Humanity and The Ambiguous History of Human Rights – Part II

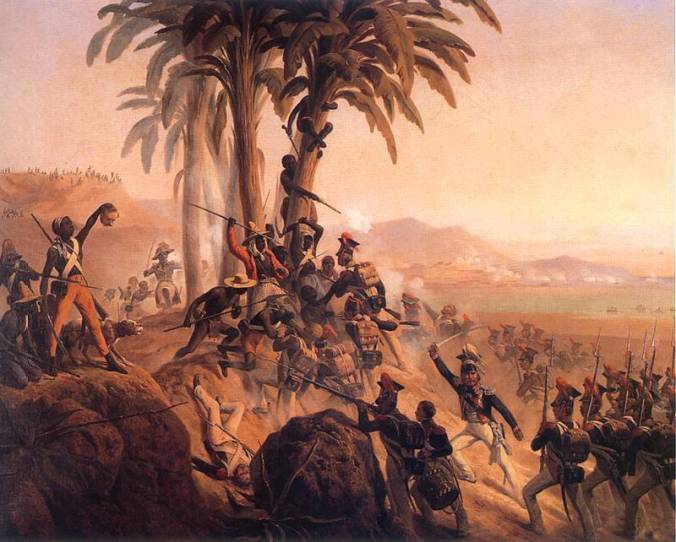

In part I of this series I outlined an alternative analysis of human rights – one that focuses on rights as the institutionalisation of particular values and relationships, specifically as responses to the question of what obligations and privileges grant political authority legitimacy. This leads to a focus on the act of claiming rights as a way of reconstructing the social order. To clarify and develop this analysis of rights I look at the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which is taken by supporters and critics alike as the foundational text of the international human rights regime. This historical inquiry is intended to achieve two ends: first, to clarify how an account of rights that takes contestation and ambiguity as inherent and productive aspects of the idea of human rights alters our understanding of the development of human rights; and second, to use two key conceptual debates that dominated the drafting of the UDHR to further develop my agonistic analysis of rights by illustrating the way that claiming human rights generates contestation over the moral significance of humanity as a political identity and the reconstruction needed to produce a legitimate international/world politics.

Narratives of Consensus and Imposition

The fundamental debate over human rights has been, and continues to be, over whether human rights are universal or not. There are clearly identifiable camps on both sides of the issue – those convinced of the universality of human rights and anxious to move past such basic questions on one side, and on the other those who think human rights are a compromised project born of an assimilative Western universalism that is best overcome or abandoned – and these opposing views of human rights strongly affect how we understand their historical development. History does not speak for itself, this much we know, but the history of human rights in particular suffers from a lack of awareness – an awareness of how our understanding of what rights are and how they are justified affects our understanding of historical events.

In the paper presented at ISA I trace out these contrasting narratives more carefully, but the broad strokes can be made in terms of consensus and imposition. In the consensus narrative, the UDHR, and the post-WWII period more broadly, represent a moment of consensus in which a fundamental moral truth was discovered (or constructed), which affirmed a comprehensive list of rights possessed by all members of the human family and which served (and continues to serve) as an ideal we should strive to implement through reform of international politics. The counter narrative of imposition re-frames the consensus achieved in the UN General Assembly vote in 1948 as a moment of Western liberal imposition, suggesting that the victors of WWII declared the universality of liberal values and politics by fiat,i mposing them upon the rest of humanity. Continue reading