A guest post from Charlotte Heath-Kelly,  Associate Professor in Politics and International Studies at the University of Warwick. Charlotte is author, most recently, of Death and Security: Memory and Mortality at the Bombsite, and ‘Survivor Trees and Memorial Groves’ in Political Geography. She is the author of very many other publications on terrorism, counter-terrorism, memory politics and critical security studies, and is currently both an ESRC Future Research Leader and Principal Investigator on a Wellcome Trust project on counterterrorism in the UK National Health Service.

Associate Professor in Politics and International Studies at the University of Warwick. Charlotte is author, most recently, of Death and Security: Memory and Mortality at the Bombsite, and ‘Survivor Trees and Memorial Groves’ in Political Geography. She is the author of very many other publications on terrorism, counter-terrorism, memory politics and critical security studies, and is currently both an ESRC Future Research Leader and Principal Investigator on a Wellcome Trust project on counterterrorism in the UK National Health Service.

Prevent is a significant part of the UK’s counterterrorism strategy. It focuses on the early detection of radicalisation. The Counterterrorism and Security Act 2015 placed a statutory duty on the public sector (schools, colleges, doctor’s surgeries, hospitals, social services, probation services, prisons) to train staff to notice signs of radicalisation, and make referrals to the authorities. On the 13th December 2018, the third annual instalment of Home Office statistics for Prevent referrals was made public. 7,318 people were referred to Local Authority Prevent boards in 2017/18.[1] Much in the bulletin replicated statistical reports for previous years. The education sector still refers most people to Prevent (2,426 referrals in 2017/18), and 95% of people referred do not receive deradicalisation mentoring known as Channel support. Yearly reports show us that the vast majority of people referred to Prevent are not judged to actually follow an extreme political or religious ideology, raising serious questions about the quality of referrals.

For those familiar with the Home Office’s statistical reporting, this all made for familiar reading. But, something new was introduced in the December 2018 statistics. A new category was added to describe the ‘type of concern’ presented by each referred person. Alongside commonplace descriptors of ‘right wing extremism’, ‘Islamist extremism’ and ‘left wing extremism’, a new category of ‘mixed, unstable or unclear ideology’ appeared. The Home Office explain that this category has been introduced to reflect those persons which ‘don’t meet the existing categories of right wing or Islamist extremism’. Instead, it reflects the growing number of referred persons whose ‘ideology draws from mixed sources, fluctuates’, or where the individual ‘does not present a coherent ideology, but may still pose a terrorism risk’. Up to 38% of referrals in 2017/18 were grouped as ‘mixed, unstable or unclear ideology’.[2]

At this moment, we reached a threshold in the history of terrorism and counterterrorism. By endorsing a conception of radicalisation without ideology, the Prevent Strategy has jettisoned a major component within almost all definitions of terrorism: its ideological motivation and political character. The ‘politicality’ of terrorism is seldom adequately defined, but provides the boundary which separates political violence from criminal or pathological violence. Alex Schmid and Albert Jongman analysed 109 definitions of terrorism used by officials and academics. They found that its ‘political’ nature appeared in 65% of those definitions – making it the second most common feature in terrorism definitions, after the quality of ‘violence/force’. The ideological motivation of militants is thought to be an important component of terrorism because violence is deployed with communicative intent. Interviews with ex-militants have shown that they deliberately use violence alongside propaganda to threaten the state’s monopoly on force – weakening the Leviathan image of the state and encouraging societal rebellion.

The politicality of terrorist violence qualifies it as a security issue for the state, rather than an issue of mass murder or criminal conspiracy (although it also satisfies these criteria). In the past, politicians have used strong rhetoric to question the politicality of political violence – such as Margaret Thatcher’s denunciation of Irish Republican militancy as criminal rather than political. However in the context of the Troubles (and the assassinations of senior figures in Westminster and Royalty which preceded the statement), Thatcher’s proclamation was transparent. In the 1980s the British Government was engaged in such a difficult political conflict that it resorted to depoliticization, to play to its supporters in Loyalist and mainland constituencies. The denial of political violence was itself political.

So what has provoked the contemporary depoliticization of terrorist tactics? Given that ‘mixed, unstable or unclear ideology’ has slipped its way into a Home Office statistical report, rather than being announced by the Prime Minister in a policy speech, we can safely assume that the depoliticization is not an act of political rhetoric. Unfortunately the situation in which British counterterrorism policy current finds itself is more complicated, and perhaps even more concerning. The epistemic and practitioner communities involved in delivering Prevent present terrorism as the unintended conclusion of an accidental journey – embarked upon without clear ideological intent in many cases.

Safeguarding Vulnerable People from Ideological Abuse: Terrorism as Grooming

The increasing focus of counterterrorism policies on the ‘vulnerabilities’ of persons to radicalisation has led us to this point. The ‘Channel Guidance’ issued by the Home Office describes the Prevent program as a ‘multi-agency approach to identify and provide support to individuals who are at risk of being drawn into terrorism’. Its commitment to pathologising potential terrorists as victims should not be underestimated, seeing as the immediately invokes The Children Act of 2004 as its reference point – which placed the protection of children on a statutory footing. Linking counterterrorism surveillance with the protection of children from physical and sexual abuse functions to legitimate the Strategy:

Section 11 of the Children Act 2004 places duties on a range of organisations and individuals to ensure their functions (including any that are contracted out) to have regard to the need to safeguard and promote the welfare of children […] Whilst the Channel provisions in Chapter 2 of Part 5 of the CT&S Act are counter-terrorism measures (since their ultimate objective is to prevent terrorism), the way in which Channel will be delivered may often overlap with the implementation of the wider safeguarding duty, especially where vulnerabilities have been identified that require intervention from social services (Home Office 2015: 4).

By placing Prevent and Channel within the frame of safeguarding, Britain’s counter-radicalisation narrates the pre-terrorist subject as a vulnerable person: one susceptible to grooming abuse and who cannot protect themselves. This sets up a duality between ‘the radicalisable subject’ and ‘the radicaliser’, presenting one as victim and the other as a predator. Prevent is then presented as a safe haven for all those at risk of ideological-grooming, where they can ‘receive support before their vulnerabilities are exploited by those that would want them to embrace terrorism, and before they become involved in criminal terrorist related activity’.

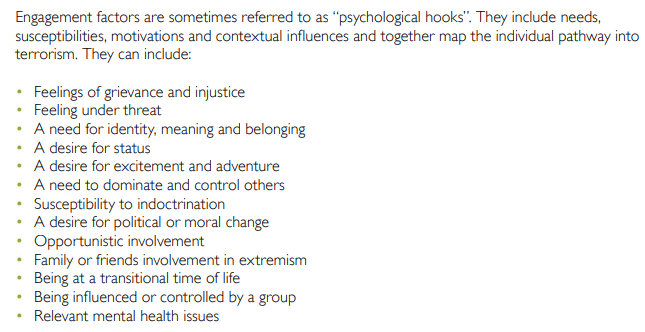

In this framing, Prevent practitioners and officials become white-knights who can intervene in desperate and complex circumstances to save a vulnerable person – and not the practitioners of nationwide counterterrorism surveillance. The ideological components of militant recruitment are recast as extremist grooming performed upon persons pathologised as ‘vulnerable’. The Vulnerability Assessment Framework (VAF) lists 22 factors used to determine radicalisation by Prevent officers, presented in the style of a psychological ‘structured judgement’ – a type of evaluation which is professionally normed and performed only by trained clinicians (unlike Prevent):

However the scientific validity of these risk typologies has been subject to intense criticism by Forensic Psychologists, as well as professional bodies representing clinicians, and charities concerned with the profiling of Muslims undertaken on this quasi-scientific basis.

Safeguarding as Surveillance; Surveillance as Safeguarding

The performance of Prevent as ‘safeguarding’ is meant to reassure the public that Prevent only provides support vulnerable people who might be ‘groomed’ into supporting/becoming terrorists. This rhetoric of protection softens the appearance of the strategy, so that the nationwide extension of counterterrorism responsibilities can be facilitated without robust opposition. This is not a war fought with an enemy, but a series of apolitical protective interventions undertaken in the style of social service response. But to accept the depoliticised framing of Prevent as ‘safeguarding’, one must ignore multiple legal, professional and experiential realities.

Firstly, safeguarding is governed by an established set of protocols and laws – which Prevent blurs to the points of meaninglessness. The Care Act 2014 collects and formalises standards for safeguarding. It defines adult safeguarding interventions as occurring when:

an adult has needs for care and support (whether or not the local authority is currently meeting those needs); is experiencing – or is at risk of – abuse or neglect; and as a result of those needs, cannot protect themselves from that abuse or neglect.

In the context of adult safeguarding, care and support needs are formal criteria including severe mental health needs, dementia, significant disability, homelessness and drug/alcohol addiction. The British Medical Association emphasises that these needs alone do not mean an adult should face a safeguarding intervention, as they still maintain agency. Rather, an adult with such needs who simultaneously faces financial, physical, psychological or sexual abuse can be given protective assistance by safeguarding teams.

But Prevent bypasses the ‘care and support needs threshold’ for safeguarding – advocating that an unspecified process of ideological grooming constitutes abuse, and that this grooming is potentially dangerous for every member of society. By removing the ‘care and support needs threshold’, every member of society becomes a potential subject of safeguarding intervention regardless of their agency and capacity. Prevent is divergent from safeguarding protocols and laws.

Secondly, the information governance standards usually associated with safeguarding are bypassed in Prevent referrals. Safeguarding referrals strictly require informed consent for personal information to be shared with other agencies. Exceptions can be made when the person lacks mental capacity to give informed consent, or a serious crime has been committed, or people are at risk of harm. However, the Prevent Leads and safeguarding professionals interviewed in academic studies of Prevent in the NHS all confirmed that they have never obtained consent before making a Prevent referral.

Furthermore, NHS England has released information governance guidance for Prevent referrals which emphasises that consent is not required to share information. The justification for not informing patients of a Prevent referral is the ‘prevention of crime’ exception to the Data Protection Act, which enables public sector information sharing in the public interest without prior consent. This exception is commonly used in Prevent referrals, where referred persons often don’t find out they have been reported until a Police Officer knocks on their door.

There is a major contradiction with safeguarding protocol here. If Prevent operates in an upstream, non-criminalised space, then why are public sector workers using the criminal exception to the Data Protection Act to make referrals? The Prevent pathway is not designed to take reports of imminent crime or terrorist conspiracy – such reports should be phoned through to the emergency services or police. So what kind of crime is thought to be imminent in the ideological discourse or disenfranchised status of those people referred to Prevent? None. The ‘crime prevention’ exception is pragmatic and expedient, facilitating the greatest number of early-stage referrals for evaluation. The apolitical safeguarding framing of the Prevent Strategy enables the rollout of surveillance under the cover of benign protection.

Finally, to accept the Prevent Strategy as a safeguarding procedure one must ignore or refuse the evidence that referrals can damage wellbeing. While Home Office statistics outline the support provided to Prevent referred persons through Channel or public sector organisations, nearly 500 people have applied to the charity Preventwatch for support after discriminatory and/or traumatising experiences of Prevent referral.

But Preventwatch is one of those Muslim organisations which is critical of Prevent, and was labelled by Home Secretary Sajid Javid as being ‘on the side of extremists’ for its publication of their testimonies. It seems that organisations led by people of colour and faith are to be vehemently dissuaded from allying with referred persons and highlighting problematic, and sometimes racist, interventions. Despite all the government’s efforts to frame terrorism as apolitical vulnerability to grooming, and to present Prevent as neutral safeguarding, the politicality of political violence resurfaces in the Home Secretary’s attempt to silence criticism.

Counterterrorism operates in securitised terrain, no matter how much officials protest that radicalisation is apolitical and that Prevent is safeguarding. Everything about the use of care structures in the service of counterterrorism is ideological, even if the Home Office cannot discern the political opinions of 38% of people referred to its deradicalisation program.

[1] The real figure is much higher, as the statistics only include those referrals which reach aren’t deemed inappropriate or malicious.

[2] While the Home Office doesn’t give an exact figure for this, the other ‘types of concern’ listed (right-wing and Islamist extremism) only made up 62% of referrals.