The third commentary in our forum on Robbie’s The Black Pacific, this time from Ajay Parasram. Ajay is a lecturer and Doctoral Candidate at Carleton University in Ottawa, unceded Algonquin Territory. His dissertation considers the gradual de-politicization of the colonial norm of “total territorial rule” emerging out of the collision of local and European ontologies of territory in mid-19th century Ceylon (Sri Lanka). One or two more posts to come before Robbie’s rejoinder.

I read The Black Pacific while walking through Coast Salish territories on Turtle Island, known in colonial vernacular as Washington State, USA, and the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, Canada. Attesting to the wide reaching applicability of the ideas advanced within this book, I engage it by drawing examples from Turtle Island, where I live.

The Black Pacific asks readers to reconnect with our shared humanity through cultivating a decolonial science of “deep relation.” This starkly contrasts with the prevailing “colonial science” of categorical separation and developmental hierarchy that is essential to ‘uni-versal’ modernity. To understand the distinction between “deep relation” and “categorical separation,” Shilliam says “We must start by acknowledging that the manifest world is a broadly (post)colonial one, structured through imperial hierarchies that encourage the one-way transmission of political authority, social relations and knowledge from the centres outwards” (20). Colonial science depends on the rigid separation of manifest and spiritual domains, as well as the separation of people into categories such as “enslaved, indentured, native, free, poor and masters. None can relate sideways to each other. They are fixated by the gaze of Britannica, the master” (23).

The Black Pacific is a nuanced, multifaceted call to abandon the science of separation that renders “profane” the myriad knowledges that people cultivate globally. The distinction offered between knowledge production/consumption vs. knowledge cultivation makes a valuable methodological contribution to decolonial research by treating the past (as opposed to History) as something in need of oxygenation:

Unlike knowledge production/consumption (a subaltern under-taking), knowledge cultivation turns matter around and folds it back on itself so as to rebind and encourage growth. This circulatory process of oxygenation necessarily interacts with a wider biotope, enfolding matter from diverse cultivations. (128-129)

The book oxygenates pasts, challenges the linearity of modern temporality, and refutes the ontological assertion that material and spiritual realms are separate. In service to these objectives, readers are guided through the manifest and uncolonized spiritual hinterlands of Māori, Pasifika, African, and RasTafari people. The process of this journey elucidates the emancipatory project of Black Power’s “soul power,” solidarity-building between the children of Tāne/Māui (Māori and Pasifika descendants) and the children of Legba (African descendants, see pages 14 – 19). Shilliam’s central argument is that resistance, rehabilitation, and decolonial futures can be built through deep solidarity-building that overcomes categorical separation by reaching into uncolonized pasts horizontally across territory and race. As Shilliam describes, “Colonial science has never been concerned with deep relations. It is only concerned with cutting the ties that bind for the sake of endless accumulation” (172).

Shilliam offers readers the choice of simply reformulating colonial science, or instead, rigorously cultivating a decolonial science that is able to “repair colonial wounds, binding back together peoples, lands, pasts, ancestors and spirits”(13).

Multiplicity as Deep Relation

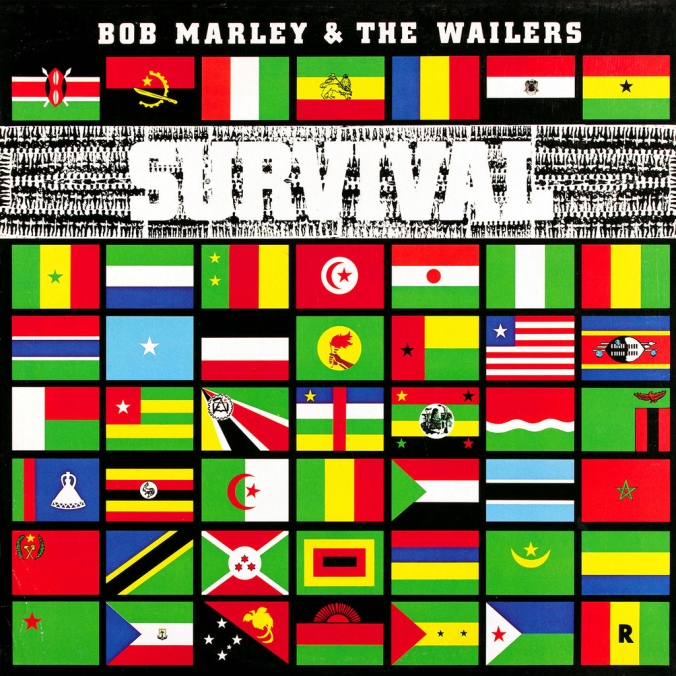

One of the great joys of graduate student life is the privilege to take long walks, immersed in a text and aided by reggae to deafen the concrete jungle of modern society. Bob Marley & The Wailer’s album Survival is a brilliant accompaniment to be listened to in full alongside this book, especially in light of roots reggae’s important role in opening pathways for deep relations between RasTafari and Māori/Pasifika, discussed throughout the book. Perhaps a foundation for horizontal solidarity in opposition to the colonial science of separation can be found in the words and spirit of the song “Babylon System” that Shilliam invokes on page 8: “We refused to be what you wanted us to be. We are who we are, and that’s the way it’s going to be.”

Lp cover released 1979.

In the book, that refusal of the Babylon System of modern/colonial categorization is accompanied with alternative guiding principles of unity embodied in the RasTafari “I and I” and the Māori “tatou tatou,” which act like a lantern casting light on the many decolonial pathways that colonial science has abandoned. Deep relation exposes the radical political, spiritual, and rehabilitative potential of one love. Said differently, it is a kind of “multiculturalism before Multiculturalism: of multiplicity as deep relation rather than categorical separation” (184). This is one way of fostering an anti-colonial solidarity that does not submit to the divisiveness of identity politics, nor the liberal narcissism of “sameness.” Instead, “grounding” is the conceptual framework in the text, and it emerges from the Māori principle of whakapapa and the RasTafari principle of grounation. As Shilliam describes,

Cognate to whakapapa, but adding an explicitly political impulse, grounation etymologically brings together ground, foundation and nation. As such, grounation announces the binding together of manifest and spiritual domains guided by the collective pursuit of self-determination. (27-28)

Deep relations, made possible through groundings, are a process of meeting and learning that connects the material world to the ancestors, all the way to the “spiritual hinterlands” in which the oldest of relations walk together in solidarity:

the ancestors are meeting because we have met. We can mark this material-and-spiritual relationality with the Māori term tatou tatou, that is, “all of us and all of us,” meaning everyone must be recognized as relatable entities rather than as categorically segregated objects. (23)

Building the book firmly on Māori and RasTafari theoretical foundations effectively de-links this project from tired and inappropriate Western theoretical foundations, and in so doing, Shilliam offers methodological, theoretical, and empirical leadership in how to do decolonial scholarship. One of the great strengths of grounding as explained in the book is that it is not a process of same-making (i.e., the denial of differences and assertion of uni-versal experiences that is essential to colonial science) nor is it a process of pluralism that harkens a descent into a spiral of cultural relativism. Grounding does “not seek to collapse domains, but rather, to make their agents relatable and their energies traversable” (21). Said another way, it is a process of meeting and learning between human siblings in the presence of their ancestors, in order to discover and recover ways of knowing and being that are politically powerful, joyful, and rehabilitative. It is well described in the grounding examples offered in the text between RasTafarai and Māori musicians:

Kirk Service found many resemblances between his Africentric cosmologies and those of Māori…At the time, Chauncey Huntley expressed his appreciation – and understanding – of the relating skills of his hosts thus: ‘When you just go and shake a man’s hand, it’s over. But when you bring him to a place where all your fathers rest and sing him a song fe get on the same vibrations as him, and him sing you back a song, you know? Yes! That’s what I call a greeting! (99)

Who can deny the depth, warmth, and power conveyed through such a greeting, especially in contrast to the clammy cold handshakes and pithy introductions that recite polite pleasantries about earning coin?

“There are no subalterns reading this book” (183)

For those who have endured many years of academic indoctrination into modern/colonial thinking, The Black Pacific is a difficult, important, and rewarding read. It begins by excommunicating the concept of the “subaltern” (4-12), done in part by linking the trope of the subaltern with the helpless “fatal impact” thesis that argues the moment of contact with Europe would have set in motion an inevitable chain of events leading to indigenous subordination (7). Over-valorizing European contact – as colonial science in all its variations does – makes the absurd assumption that the most defining characteristic of a people is their relationship to Europe (see Blaser 2013 and de la Cadena 2013). Shilliam recognizes and appreciates the political context in which subaltern studies emerged, but concludes that “the category of the subaltern becomes singularly unhelpful, if not meaningless” (8) for the purposes of decolonial projects which always exist in practice and never simply in the abstract.

Subaltern studies, as a historiographical intervention into Hegelian World-History, indeed democratizes and pluralizes History, yet it continues to do so on the ontological and epistemic terrain of national Histories that reflect the earth-writing (geo-graphy) of imperial design (see Ó Tuathail 1996). Modern/colonial categories such as “land” or “nation” fail to capture the depth of meaning residing within ontologies and practices that are other than modern/colonial. For example, writing about the incompatibility of Euro-centric understandings of sovereignty and indigenous nationhood, Mohawk scholar Taiaiake Alfred (1999:56) observes:

Traditional indigenous nationhood stands in sharp contrast to the dominant understanding of ‘the state’: there is no absolute authority, no coercive enforcement of decisions, no hierarchy, and no separate ruling entity. In accepting the idea that progress is attainable within the framework of the state, therefore, indigenous people are moving towards acceptance of forms of government that more closely resemble the state than traditional systems. Is it possible to accomplish good in a system designed to promote harm? Yes, on the margins. But eventually the grinding engine of discord and deprivation will obliterate the marginal good. The real goal should be to stop that engine.[1]

Alfred’s distinction between indigenous nationhood and the state speaks to the limitations inherent to accepting the ontological assertions of Euro-centric social science when decolonial research is what you are after. Ranajit Guha (2002: 45) is right to mark India’s entry into World-History at 1802, when Ramram Basu wrote Raja Pratapaditya Caritra and boxed Bengali pasts into sovereign narratives comprehensible to his modern/colonial employer, the British East India Company. The question remains, however, why must survivors of colonial violence continue to force diverse and nuanced practices of knowledge-cultivation into terms that are legible and audible to colonial science? (We’ve been trodding on that winepress for much too long.) The intellectual and political terrain upon which subalterns might exist cannot allow for meetings between distant relatives of the human race: there is no grounding here, which brings about the just rage of those who constitute the colonial side of the modern/colonial coin. Like Kwakwaka’wakw artist and activist Gord Hill animates, Indigenous people of the Western Hemisphere have been engaged in over 500 Years of Resistance to colonialism – subalterns exist only in colonial science because the terms on which they engage are defined by the colonizer.

Deep Grounding and Black Power

Between chapters 2 and 3, Shilliam situates the radical spaces opened by Black Power that enabled a generation of anti-colonial Māori and Pasifika youth to “ground” horizontally across oceans through the empowering politics unfolding in Africa, Turtle Island, and the Caribbean. An older generation of Māori, The Te Aute Old Boys, wanted to operate within the modern settler-state structure to bring about mana motuhake by trying to “to balance Pākehā means with Maori ends”(43). Shilliam describes how “the young warriors now saw their fluency in the Pākehā world as destructive and disabling of Māori ends: ‘The Māori just wants to be what he was and is, a Māori! He doesn’t want to be a brown skinned New Zealander. He is proud of his ancestors, and ancestral background, and he is proud of his customs and traditions’” (43). In a way, the struggle of the Maori warriors relative to The Te Aute Old Boys is similar to the obstacle of modern/colonial science described above through subaltern studies as well as Alfred’s challenge regarding the state – are modern/colonial frameworks capable of bringing about mana motuhake, or are there better ways? Shilliam argues that Black Power enabled a spiritual and material process through “inhabiting blackness” and fostering deep relation and solidarity with movements on Turtle Island as well as anti-apartheid movements in South Africa. “In a generational sense, then, young African-American radicals spoke more directly to the situation of Maori youth than many of the latter’s kaumatua (elders)” (45). It was through grounding between RasTafari, Black Power activists, and the children of Legba that Māori and Pasifika youth were able to overcome colonial geographic/racial separation; they reached into decolonial pasts to see the shared struggle of the children of Legba and the children of Tāne/Māui.

This deep relation occurs, in the material domain, in a specific moment of global politics: the rise of Black Power and the official decline of administrative colonial rule in the mid-late 20th century. New pathways that were perhaps shrouded to Te Aute Old Boys were open to indigenous youth growing up in this global context, and they could access these decolonial pathways through reggae (like many indigenous youth of Turtle Island do through hip-hop and electronic music), and traverse them through solidarity-building. For example, Shilliam discusses the Polynesian Panthers’ merging of indigenous relationship-structuring with Huey Newton’s concept of “revolutionary intercommunualism” to reconnect Māori and Pasifika peoples. As Shilliam explains, “the Polynesian Panthers sought to redeem the tuakana/teina relationship between Pasifika and Māori by mobilizing Blackness as a political identification through which to bind together the diverse yet related peoples of (post)colonized Oceania in a global anti-colonial project of restitutive justice” (58). The common experience of racism was the political rationale.

The alternative pathways charted in the book make visible how anti-colonial solidarity-building can be done across culture on different terms of reference than the ones popular in most academic writing. Invocations in this book are not to Kant or Rousseau, they are to Tāne/Māui, Legba, Ham and Shem. The book moves beyond criticism and offers a decolonial pathway for reconstruction and rehabilitation for all who will take their appropriate place around the campfire of liberation (167). In doing so, the text demonstrates that opposite the claims of modernization or development theories, it is the modern/colonial global system that is the problem. Said another way:

…the Babylon System is the vampire, falling empire,

Suckin’ the blood of the sufferers

Building church and university

Deceiving the people continually.

Marley’s lyrics, like Shilliam’s, speak not only to the problem of the modern/colonial condition of Babylon, but also to the epistemic injustices served by its reification via powerful modes of knowledge production and consumption in the institutions of church and academy.

In the last chapter, entitled, “Africa in Oceania,” the conceptual, methodological, and empirical offerings of the text come together. This unorthodox chapter pulls together the spiritual hinterlands (the un-colonized past) with the material realm and rapidly transports the reader across time, place, and peoples, artfully disorienting modern/colonial presents in order to re-orient decolonial realities. The written archival sources join with the living knowledge traditions and Shillam teleports across oceans, land, and ancestors, meeting the characters that inhabit decolonial science – not Cooke and Colombus, but the Jamaican cook onboard a beached ship at Maketu. Rather than stating the obvious – that colonial archives don’t talk about regular people –Shillaim instead turns over the past and oxygenates it by asking plausible questions: “This Jamaican cook: perhaps he is one of the riotous subjects?” (181). Like Sufis spinning in prayer, as a reader you cannot help but emerge from “Africa in Oceania” with a dizzying awareness that enables the decolonial connections that are carefully woven throughout the preceding chapters to fall into place.

Territoriality of Spiritual Hinterlands?

Shilliam does an elegant job showing the complex relations through which the gods of Christians, RasTafari, and Māori were bound together (see chapter 7). There are nods throughout the text regarding Africa as the ancestral home of all people, demonstrated through whakapapa in Aotearoa back to Africa (99). However, not all whakapapa lead to Africa, and here on Turtle Island, Pākehā[2] argue that humanity’s shared origins in Africa discredits indigenous knowledge that whakapapa to creation not just on this land, but in some cases, as part of this land. The territoriality of the spiritual hinterlands thus raises an important tension between colonial and decolonial science. As Dene scholar Glen Coulthard explains,

In the Weledeh dialect of Dogrib (which is my community’s language), for example, “land” (or dè) is translated in relational terms as that which encompasses not only the land (understood here as material), but also people and animals, rocks and trees, lakes and rivers, and so on. Seen in this light, we are as much a part of the land as any other element. Furthermore, within this system of relations human beings are not the only constituent believed to embody spirit or agency. (Coulthard:61)

Such ontologies of land appear incompatible with Biblical accounts that assume that animals and nature are separate from (and in some readings) subservient to humans. The Black Pacific distinguishes between the arrogant imperialism of missionaries guided by the philosophy of John: 5.23 (131) and details several ways through which grounding occurs between indigenous, RasTafari, and Christian spiritual realms. For example:

Toleafoa argues that the special relationship between brother and sister, prevalent in many Oceanic cultures, was done great damage to when missionaries proselytized that only one beloved relationship was allowed – to a Jesus that they claimed to be the sole avatars of. This is surely one of the deepest colonial cuts in need of repair: to segregate a people from creation, thereby commanding them to surrender their souls to the master’s sun. (85)

In this way, Shilliam works to de-colonize the Bible and the Abrahamic traditions that grew from it. For example, chapters 6 and 7 speak to the Maori indigenization of the god of the Bible as their own (142). RasTafari offers a de-colonized biblical pathway that many Māori chose to inhabit. The fact that Māori elders would occasionally whakapapa back to Africa (99) suggests that there is no ontological tension between being tangata whenua (people of the land) while identifying with a spiritual hinterland that is not grounded to territory in the way that it appears to be for the Dene of Turtle Island or the Quechua peoples of the Andes.

I was surprised by this, and wondered if there might have been more to say about land, creation, and the tension within Māori/Pasifika groups concerning how to engage the spiritual realm of the Bible. Locating the spiritual hinterlands in the cosmological terrain of an Abrahamic tradition – even a de-colonized one — risks leaving ontological and territorial assumptions under-interrogated. The book of Genesis, for example, is often mobilized to justify the separation of humanity from nature long before colonial science wielded it’s surgical knife towards insisting on this separation. The establishment of hierarchies of living beings and segregation of material and spiritual realms is a constituting component of post-enlightenment secular science, which appears to be fundamentally at odds with many indigenous knowledge systems. If the territoriality of the spiritual and ancestral realm implies a starting point in Africa, it poses a problem where indigenous whakapapa is ontologically anchored to land, such as the example of the Dene above and the many others that whakapapa to creation within and as part of the land.

Questions of this nature are important for scholars residing in settler-colonial societies who want to continue the important work that Shilliam begins in The Black Pacific. Can grounding and deep relation overcome differences that have deep roots in both the material (colonial) and spiritual (ontological) realm? Would the creator of the Dene or the Ojibway inhabit the spiritual hinterlands alongside Ham and Shem? Grounding, as offered in The Black Pacific, is likely the avenue through which to begin learning the answers to these questions, because as Shilliam makes clear from the beginning, there can be no abstract theorizing in decolonial science (8). This is perhaps why modern society has not found such answers. Imagine the world we might inhabit today had Cooke, Colombus, Cabot, Cortez, (and all the other ‘C’s of colonialism) practiced deep relation instead of genocide and slavery.

Conclusion

In parting, The Black Pacific is a smashing book about building de-colonial pathways and roads off modernity’s beaten path that are capable of navigating from Ethiopia to Aotearoa to Turtle Island to the Caribbean, without having to stamp a passport in London, Rome, or Washington. As a reader, you begin by stumbling across the same campfire that Jean-Paul Sarte discovers in his preface to Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth. You have nothing to fear however, because this campfire is of a very different nature. As Shilliam puts it towards the end of the book, “Take your appropriate place around the campfire of liberation; perhaps it is at the front, at the side, or at the back. Tatou tatou. I and I. Let us tell some stories of Africa in Oceania.” We arrive at the campfire of liberation via decolonial footpaths like the one Shilliam guides us along. This path was about groundings between the children of Tāne/Māui and the children of Legba, but Shilliam throws the gauntlet to the reader to begin oxygenating pasts in order to recover other pathways across time, place, and domains that can lead us to the campfire of liberation. And as Bob Marley reminds us, “no water can put out this fire.”

References

Taiaiake Alfred. Peace Power Righteousness: an indigenous manifesto. Don Mills: Oxford University Press, 1999

Mario Blaser, “Ontological Conflicts and Stories of People In Spite of Europe: Towards a Conversation on Political Ontology” Current Anthropology 54/5 (2013): 547 – 568

Bob Marley & The Wailers, “One Love/People Get Ready,” Exodus. Harry J. Studio Kingston Jamaica and Island Studios, London England. Release June 3, 1977

Bob Marley & The Wailers. Survival. Tuff Gong Recording Studio, Kingston Jamaica, 1979.

Damian Marley and Nas. Distant Relatives Universal Republic Def Jam, Los Angeles and Miami, 2010.

Marisol de la Cadena, Earthbeings: Ecologies of Practice Across Andean Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.

Marisol de la Cadena, “The Politics of Modern Politics Meets Ethnographies of Excess Through Ontological Openings” Fieldsights – Theorizing the Contemporary, Cultural Anthropology Online. Jan. 13, 2014.

Glen Sean Coulthard. Red Skin White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014

Gord Hill The 500 Years of Resistance Comic Book Vancouver: Arsenal Press, 2010

Gearoid Ó Tuthail, Critical Geopolitics: The Politics of Writing Global Space. London: Routledge, 1996

“Rebel Music: Native America” Rebel Music. Available online.

A Tribe Called Red, “Burn Your Village to the Ground” Special ‘Thanksgiving’ online release. Available online.

[1] See also Alfred’s 2015 presentation on Research and Indigenous Resurgence: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tuXc1uuMehU,

[2] I use Pākehā here not to refer to people of European descent, but as outlined in the book by Maori Black Power gang president Reitu Harris: “to me the word ‘Pākehā’ no longer stands for ‘European’…it stands for a type of person who…when it rains, will rush for shelter themselves and not care about others getting wet.”

Pingback: This blog by PhD candidate Ajay Parasram was published as part of a week-long symposium on the book The Black Pacific by Robbie Shilliam - Department of Political Science

thanks for sharing !

LikeLike