Britain’s Conservative government recently released its much-awaited (or much-dreaded) ‘green paper’ on higher education (HE), a consultation document that sets out broad ideas for the sector’s future. Masochistically, I have read this document – so you don’t have to. This first post describes and evaluates the centrepiece of the green paper, the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF), and measures on ‘social mobility’.

There have already been several commentaries on the green paper, many pointing out the obvious: that the British government has reduced higher education to a private investment that students make to acquire ‘skills and job readiness’ (p.8), whose public benefit is limited to ‘increasing productivity’ by addressing a ‘sharp rise in skills shortages’ (pp. 10-11). That much was already obvious in the Browne Review, but in this green paper all references to the non-economic value of education have evaporated entirely. This is philistine utilitarianism taken to its extreme, by a bunch of people educated in History and the Classics.

Another general point to consider is this: just how much regulatory power do state managers really think they can exert over institutions whose income now largely comes from private not public sources? As I’ve written elsewhere, UK HE combines the worst aspects of the market with the worst aspects of Soviet-style bureaucracy. The British state has become highly adept at shifting the financial burden of services from the public to the private while retaining vastly disproportionate regulatory power. A simple example is the conditionality attached to Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) studentships: recipients must be given quantitative research methods training. As a result, universities must be able to provide this training and end up giving it to everyone, despite the pathetically small number of ESRC studentships received (and despite its general disutility to most students).

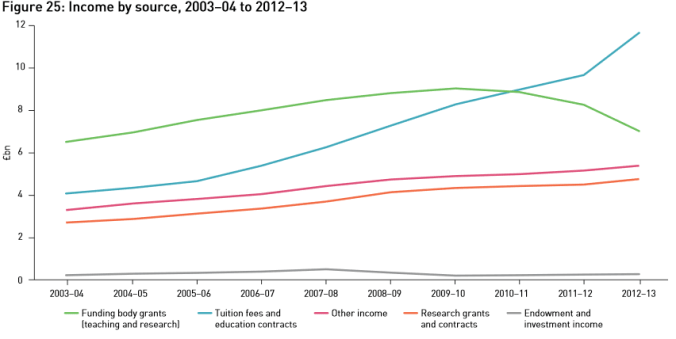

At a broader level, following the ‘reforms’ in the last parliament, public money is now a increasingly minor proportion of income for UK universities. As the chart below shows, the combined income from tuition fees, external research grants and elsewhere now exceeds the public investment via funding body grants. In 2015/16, the teaching grant for the whole sector was just £1.42bn (HEFCE 2015: 2). Since the sector’s total income in 2013/14 was £29.1bn (UUK 2014: 23), the HEFCE teaching grant comprises under 5% of income. What little public ‘support’ for HE teaching is still provided now comes entirely through the state backing of the student loans system. The state’s contribution here is a notional one; it only pays if students fail to repay their loans (which will certainly happen, but that is an unintended byproduct of a disastrously designed system, not an intentional ‘subsidy’).

UUK 2014: 24

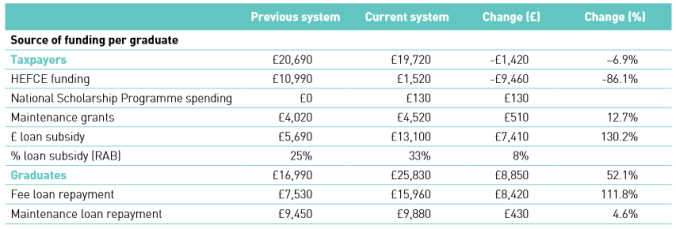

UUK 2013: 11

Despite this dramatic shifting of the burden of supporting HE from the public purse to private individuals, and the overt aspiration of converting HE into a fully functioning marketplace, the state apparently still feels entitled to subject universities to stupendous, and increasing, amounts of regulation. This is, of course, how neoliberalism works in practice: entrepreneurs’ animal spirits are not simply unleashed; a market has to be made through state regulation. But one question about what follows is whether the state’s reach now exceeds its grasp.

A final preliminary comment is that, as with other recent ‘reforms’, there is no real evidence that the changes proposed in the green paper are actually necessary. In HEFCE’s recent consultation on quality assurance, since there was no suggestion that the system was in any way broken, I had to conclude that its main purpose was to weaken quality assurance to enable private providers to enter the market in greater numbers. Likewise, the putative reasons for change given in the green paper – that teaching is being neglected for research, that students are demanding greater transparency, and that employers are dissatisfied with graduate quality – have been debunked by Dorothy Bishop.The NSS data have been deliberately ‘spun’ by the minister of state to do down universities. As Bishop argues, when the stated goals do not match reality we rightly suspect unstated goals are the real guiding force, which again means the government’s concern to open up HE to ‘new providers’, i.e. private companies wishing to become ‘universities’.

Jo Johnson MP, minister for HE, enjoying his own ‘student experience’.

The Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF)

The TEF is of course the centrepiece of the green paper. To put it simply: if you hated the REF, you’re really gonna hate the TEF.

The government’s ideas for the TEF are as follows. Every department would be subject to review on a 5-yearly basis by an disciplinary panel comprising educational experts, students and employers. These panels would review quantitative metrics and qualitative evidence on teaching quality submitted by institutions. But TEF ‘levels’ will be awarded on a rolling basis to institutions as a whole, not individual subject departments. TEF Level 1 would merely involve meeting the basic quality assurance standards – subject to a recent review by HEFCE (slated by me and others here). There would be up to three additional TEF levels, using metrics and standards yet to be devised – subject to a further ‘technical consultation’ next year. Institutions that achieve higher TEF levels would have their maximum fee cap raised in line with inflation. They are also expected to be able to increase their student intake due to the ‘reputational’ gain. This will ‘incentivise’ institutions to ‘reinvest the additional income’ in further improving teaching quality and drive a virtuous cycle. The government also wants to encourage universities to shift to a grade point average (GPA) grading system, though this is not anticipated to be a compulsory part of the TEF.

There are endless problems with these proposals, but here are just a few.

- The government clearly has no idea how to measure teaching quality. The green paper repeatedly moans about the ‘imperfect proxies’ currently used to denote teaching quality (pp.19, 20). It then proceeds to admit: ‘Because there is no single direct measure of teaching excellence, we will need to rely on proxy information’ (p.31). There is a huge amount of vague waffle about benchmarking and developing quality metrics with the involvement of the Office of National Statistics. But the green paper suggests only three concrete metrics: employment/ destination; retention/ continuation; and student satisfaction indicators (pp.33-34). These can only be understood as highly ‘imperfect proxies’ of teaching quality.Graduates’ employment is shaped by diverse factors, many of which have absolutely nothing to do with teaching quality, such as social capital, social class and networks. The government may moan that 20% of graduates are in non-graduate jobs, but this is obviously in large part because the economy is not generating high-quality graduate jobs – it is hardly the fault of university teachers. Retention/ continuation is important, but again is only faintly related to teaching quality. Students drop out of university not because their teachers are bad, but for a variety of personal, social and economic reasons beyond the control of universities. Yes, universities should support students facing difficulties and try to keep students engaged – but this is a role generally (and rightly) performed by administrative/ support staff, not teachers. And student satisfaction tells one little or nothing about teaching quality. As we all know, the NSS is extensively ‘gamed’ at most sensible institutions, which encourage students to give positive feedback to boost the ‘value’ of their degree. Moreover, there is no necessary link between ‘satisfaction’ and ‘quality’ – a point developed further below.The government itself admits: ‘these metrics are largely proxies rather than direct measures of [teaching] quality and learning gain and there are issues around how robust they are’ (p.34). In effect: we know the metrics are crap. So this is no solution to the supposed problem of ‘imperfect metrics’. This is the explicit reason why they include a resort to qualitative data submissions to TEF panels.

This is obviously a gaping hole in a scheme whose entire purpose is to grade teaching quality. The green paper breezily declares that they will develop new metrics through a technical consultation in 2016. But there is no reason to suppose that a ‘robust’ way to measure teaching quality can actually be found. If there was, it would already have been discovered. The reality is that teaching is a complex relationship between teachers and students, who each bring something to the table. Teachers bring subject expertise, pedagogic skills, experience and specialised knowledge. Students bring their prior learning experiences, their inate intelligence, their effort and drive, and their structural position, including, for example, their family’s wealth or poverty, which may dictate how many hours per week they can actually devote to their studies. Given this, separating out who or what is responsible for a given educational outcome is virtually impossible to do with anything like scientific accuracy.

- The TEF will be a REF-like bureaucratic nightmare. Precisely because metrics are not a reliable measure of teaching quality (and also because what ‘quality’ means varies by subject area) the government proposes to assign judgement to expert, discipline-specific panels, which will review the metrics and qualitative submissions by departments on a 5-year basis, with a constant ‘rolling cycle’ of assessments. If this sounds familiar, it’s because it essentially duplicates the bureaucratic monstrosity that is the REF, which involves expert, discipline-specific panels reviewing quantitative and qualitative submissions by departments on research quality on a 5-year basis. The bureaucracy and costs associated with the REF are staggering: the 2014 exercise cost HEFCE just £14m, but institutions spent £230m on constant ‘dry runs’, paying ‘consultants’ to write submissions, modelling outcomes, and otherwise gaming the system. This approach – which academics widely regard as unfit for purpose – would simply be replicated for the TEF. As I pointed out in my response to HEFCE’s recent consultation on quality assurance (QA), institutions already spend £1.1bn annually – 8% of the teaching budget – on QA. Now the government proposes to waste even more money on bureaucracy and the employment of more middle-managers and administrators (who already outnumber academics at most British universities), under the guise of providing better ‘value for money’ for students.

- The costs of the TEF very obviously outweigh its dubious benefits. Put simply, there is no good reason for universities to comply with the TEF. This relates to my introductory points on finance and the government’s reach/ grasp. The only benefits to institutions participating in the TEF is reputational gain, which might increase student recruitment, and an uplift in fees in line with inflation. So when the green paper suggests that there will be ‘additional income’ to reinvest in teaching, this is either a lie or self-delusion. Even if student numbers rise, that simply means more students to teach; it is not a rise in the ‘unit of resources’, i.e. the amount of money per student that universities have to spend. Since fee rises are capped at inflation, therefore, the best that participating institutions can achieve is for income-per-student to stagnate in real terms. Moreover, these increases would take years to feed through the system because the government does not envisage increasing fees for currently-enrolled students, only future cohorts (pp.29-30). Furthermore, the green paper states that universities ‘would be expected to bear the costs of the TEF assessment process’ (p.28). Once you subtract the hefty formal and informal costs from the extremely meagre benefits the net result is almost certainly a net financial loss. Clearly, the only way that teaching quality could be improved under these circumstances is to demand that staff do ever more with fewer or the same amount of resources. It will not ‘bring better balance to providers’ competing priorities’ (p.20), it will just intensify the pressure on staff time, when academics are already working an average of 50+ hours per week.Vice-chancellors would have to be idiots to sign up to this regime. The UCL provost has already said UCL would be ‘unlikely to submit to the TEF for purely financial reasons’. Whether other VCs will follow his sensible lead remains to be seen, of course. VCs have been extraordinarily short-sighted and supine in response to the government’s post-2010 HE ‘reforms’, so to expect a sudden discovery of backbone now may be naive. The sector is also so fragmented, with VCs primarily interested in securing market position, that any collective response would be undermined if some turncoats think they can gain by embracing TEF. I understand London Met’s VC has already suggested TEF could rebalance funding towards less research-intensive institutions like his. He needs to re-do his maths.

- The TEF will be a constantly moving target. As noted above, the government has no idea how to measure teaching quality, so universities are being asked to sign up to a regulatory system whose regulations are entirely unclear and which, indeed, is explicitly intended to ‘develop over time; the TEF will evolve as more metrics are integrated’ (p.23). This confirms that the TEF will be a REF-like monstrosity. The REF, after all, started out as a rather simple, quaint exercise where departments submitted just five outputs and four sides of A4 text; today it is a crippling burden.Again, it is sheer idiocy to submit voluntarily to a regulatory regime whose contours are constantly changing.

- The TEF will incentivise negative changes in universities. The real problem with the ‘new public management’ approach of measuring everything is that it creates strong incentives to focus on gaming the metrics and/or focusing resources on activities designed to improve metricised scores. When it comes to education, this is particularly pernicious. Take, for example, the supposed ‘proxy’ of student satisfaction scores. The green paper notes that students often use the NSS to express a desire for more contact hours (p.11). But caving to this admittedly frequent demand (even if there were extra resources to enable this, which there are not) would not necessarily improve the quality of students’ education. It would subtract time from the independent study that is crucial to higher learning. When students demand more contact hours it is often because they would prefer to be spoon-fed material, as they are at school, rather than struggling to develop their own understanding. Research shows that students express greatest satisfaction with easier courses that make them learn less. Turning ‘student satisfaction’ into a proxy of teaching quality is not a recipe for excellence; it is a recipe for dumbing down and teaching to the test. This will become particularly true if the pilots of tests of ‘learning gain’ currently underway produce a standardised examination used to test students at the end of their degrees.

As Dorothy Bishop has rightly observed, the green paper wants feedback on how to implement its plans; that the TEF will be implemented in some form is not opened to question. But as the foregoing shows, the TEF needs to be rejected in its entireity, not subjected to technical critiques and and offers of advice and refinement.

Social mobility

The only vaguely progressive aspect of the green paper is its stated concern with social mobility, by which it means access to HE by disadvantaged social groups. The government has made the charging of fees above £6,000 dependent on ‘access agreements’ with the Office for Fair Access, with universities now spending £745m annually on measures to improve access. The government’s target is to raise the participation rate of students from disadvantaged backgrounds from 13.6% in 2009 to 27.2% by 2020, and increase the percentage of Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) young people going to university to 20%. As the green paper notes, there are real problems in this domain, particularly: lower retention rates for BME students; ‘pronounced differences’ in degree attainment and progression to further education and employment between white and some BME groups; the fact that white men from the most disadvantaged backgrounds is radically lower than for their BME counterparts; and that only 3% of disadvantaged students enter highly selective universities, compared to 21% of their most advantaged counterparts (p.37).

However, despite paying lipservice to this problem, the green paper offers no real solution. The proposed TEF would break down scores by student characteristics ‘and this information will be used in making TEF assessments’, with a view to ‘recognis[ing] those institutions that do the most to welcome and support students from a range of backgrounds’ (pp.31, 20). No further detail is specified. There is no stated intention, for example, to provide a ‘handicap’ for TEF levels for institutions with large disadvantaged intakes, despite the fact these students ‘tend not to perform as well’ (p.31). Nor is there any financial incentive for institutions that deliver good outcomes for such students. There is simply nothing here, apart from a commitment to break down the data. How this is supposed to make any difference is not explained.

The only practical additional measure identified to enhance social mobility (aside from UCAS’s already-announced intention to introduce name-blind applications from 2017) is the possibility of empowering OFFA to set targets for providers that are failing to make progress on agreed widenining participation goals. Currently these goals are negotiated in the ‘access agreements’. If institutions failed to meet these new imposed targets, OFFA could decline the access agreement, meaning an institution could only charge £6,000 fees. Even if this very heavy-handed approach was legitimate, this could only work to improve access to university. It would not do anything to improve students’ attainment when they got there.

The bigger problem here is the larger debate about universities and social mobility, which the green paper does not really engage with. The big questions are the appropriate degree of responsibility that universities should be assigned for solving structural social problems, and the extent to which universities themselves contribute to these problems. If one takes the view that universities are the problem, it makes sense to place the burden on them. For example, one may argue that because white/BME student attainment varies when controlling for prior attainment and other factors, universities are systematically failing BME students in some way. However, there would still be debate as to the nature of that failure and how to overcome it. Even those sympathetic to this interpretation do not agree on what needs to be done, making it difficult to know how to proceed. Furthermore, if one takes the view that uneven outcomes are structural, driven mostly by factors beyond universities’ control, then to threaten the financial viability of universities for failing to change the situation is perverse.

Either way, the green paper largely describes the problem. It does little to solve it.

—-

HEFCE (2015) Funding for universities and colleges for 2013-14 to 2015-16: Board Decisions. 20 February.

UUK (2013) The Funding Challenge for Universities.

UUK (2014) Patterns and Trends in UK Higher Education.

Lee: this is typically incisive and illuminating and deserves a wide audience. An obvious thought that has struck me and others is that the Green Paper is indeed disingenuous about greater income for HEIs as things stand, but that it makes more sense if we project a further lifting of the fee cap in the next phase, creating different fee bands partly based on TEF (e.g. 6-9k; 9-12k; 12-15k), and perhaps also a repurposed REF (where the exercise delivers a rating influencing fee banding rather than direct resource flow from

HMG). Is this also your prediction?

LikeLike

That would make sense in theory. However, I tend to go with Andrew McGettigan on this: he thinks that the Treasury will not allow fees to rise further because of the impact on public finances, particularly further down the line when an anticipated c.45% of graduates default on their loans. You might remember that initially Jo Johnson said that the TEF would involve financial incentives, then that was dropped for a long time, before reappearing in the green paper – McGettigan argues the initial retreat reflects the Treasury’s opposition, and the very small financial incentive eventually offered suggests it has not budged very much. If the government did eventually decide to float fees further, they would probably need to change the repayment terms so that, e.g., there would be no write-off after a given period and the payments would be sequestered from your income for all eternity, a la the US. I’m not sure this would fly politically, but who knows.

LikeLike

I’m ambivalent about the TEF at the moment. On the one hand it seems like a good counterbalance to an increasingly research-oriented university culture. On the other I can imagine this just placing yet more burden on scholars who will be expected to be research superstars and teaching legends at the same time.

Nonetheless, I noted in Jones’s piece the same stock arguments that I have encountered in my engagement with the financial sector about new regulations and a pretty obvious rhetoric of futility being rolled out here.

For example, Jones says: “The green paper breezily declares that they will develop new metrics through a technical consultation in 2016. But there is no reason to suppose that a ‘robust’ way to measure teaching quality can actually be found. If there was, it would already have been discovered.”

Really? I mean, all metrics are imperfect but its seems reasonable to me that workable metrics could be put together just by asking students what they thought of courses and the teaching they receive. The idea that these survey-sourced metrics are intrinsically useless and incommensurate seems dubious to me (unless you can handle a bit of uncertainty then pretty much all attempts at regulation and institutional organization will quickly seem futile).

Already I can see that the TEF is changing the values of some Universities in terms of their hiring. And I think this is by and large a good thing! Do we really want universities full of antisocial mumblers who can churn out research but not engage students in any meaningful capacity? The TEF at least seems to bend the stick in the right direction. So, I remain undecided, but I don’t find this anti-bureaucracy rant particularly convincing. Like it or not the government does retain an influence over University HE and it seems to me that this is one of their least objectionable regulatory initiatives.

LikeLike

“workable metrics could be put together just by asking students what they thought of courses and the teaching they receive”

Well, I had thought I had addressed that very possibility already, since that is, after all, what the NSS does. Asking what students thought of courses and the teaching can be useful, but it is by no means a direct, robust or reliable measure of teaching quality. As I state in the post, students tend to report the highest levels of satisfaction with teaching experiences where they learn the least. Comparable difficulties arise with virtually every other proxy measure you can think of.

I also think you are very naive to suppose that the TEF will ‘rebalance’ universities’ priorities. Personally I would be in favour of such a rebalancing (though I would dispute your silly characterisation of excellent researchers as “antisocial mumblers” who don’t engage students – even Johnson doesn’t go that far). But that would mean placing less emphasis on research, and more on teaching. In practice, the same level of emphasis will be retained, along with greater emphasis on teaching, i.e. the exploitation of labour will simply intensify. As I have often said, the sector missed a trick when £9k fees came along. We ought to have opposed it, obviously. But if it was then imposed regardless, we ought to have said that this will obviously and deliberately inflate student expectations, so we must downgrade our research ambitions in order to cater to them. We could have forced a weakening of the REF, for example – a reduction in the number of outputs, or the extension of the survey period to once every eight years or something. Instead, as usual, we get shafted from both ends.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“by no means a direct, robust or reliable measure of teaching quality”

I’d have to know what standards you are applying here for that statement to be meaningful. How reliable? Robust in what sense? My point is that on the whole student surveys of teaching are probably good enough to supply useful metrics for comparative teaching evaluation across large sample sizes.

“I also think you are very naive to suppose that the TEF will ‘rebalance’ universities’ priorities.”

Its seems to be from the conversations I’ve been privy to at my institution. We’ll have to see what happens in practice though.

“I would dispute your silly characterisation of excellent researchers as “antisocial mumblers” who don’t engage students”

If I gave that impression it wasn’t my intention (I was being a bit tongue in cheek obviously). I was just trying to make the point that there are *some* excellent researchers who lack good teaching skills or the ability to engage meaningfully with students and colleagues.

More or less agree with the rest of your comment.

LikeLike

The burden of directness, reliability and robustness lies with those who think they can measure the quality of teaching. Lee has given at least one very good reason why that burden is not met (namely, that students tend to subjectively rate courses highly where they objectively learn the least). Now, a generalisation from that alone is problematic. But it is still a better piece of evidence than either you or HMG have offered so far as to any true measure of quality, or any genuine problem that requires the TEF to solve it. After all, the measure you prefer (NSS scores) already show that teaching is excellent and getting better all the time. Now, you might reasonably object that the NSS is bullshit, but not whilst simultaneously relying on that same NSS for your case on rebalancing funding in line with students’ judgements of what constitutes good teaching.

LikeLike

Pingback: The HE Green Paper: (Don’t) Read it and Weep – Part 2: Completing the Market | The Disorder Of Things

John Holmwood is good on why the NSS is a poor metric. http://publicuniversity.org.uk/2015/11/08/slouching-toward-the-market-the-new-green-paper-for-higher-education-part-i

LikeLike

Pingback: The HE Green Paper: (Don’t) Read it and Weep – Part 1: The TEF & Social Mobility | psychosputnik

Reblogged this on Perspectives on professional development.

LikeLike

Pingback: The HE Green Paper: (Don’t) Read it and Weep – Part 1: The TEF & Social Mobility | Forwardeconomics

Pingback: The Gold Paper – a first draft and call for participation and submissions | Goldsmiths UCU

Pingback: The HE Bill: The Final Ditch | The Disorder Of Things