The assassination of Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophia on June 28, 1914 set of a chain of events that a few weeks later led to an all-out war involving virtually all key European powers and their enormous overseas empires at the time. How did this happen?

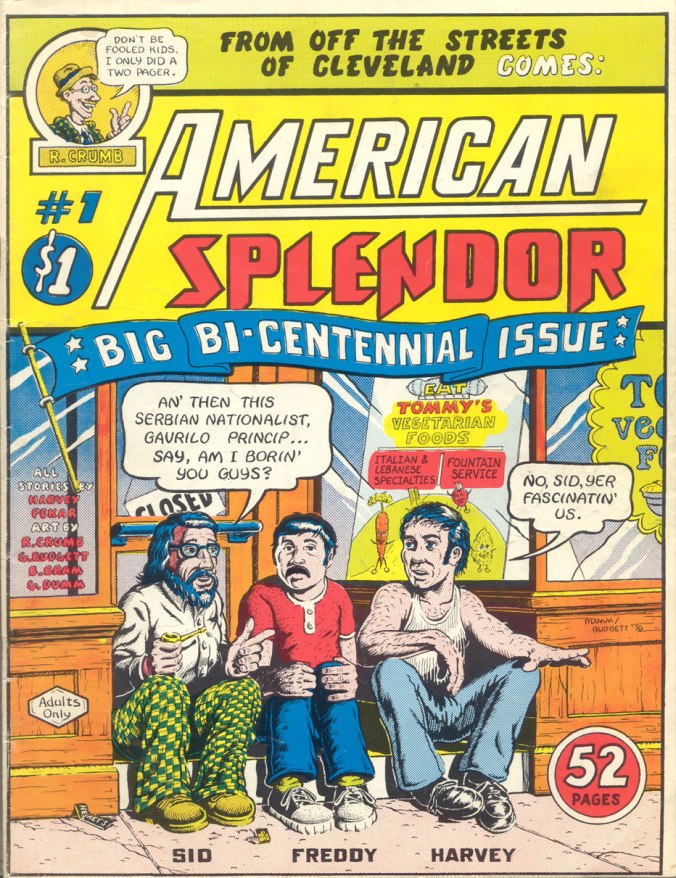

As a born and raised Sarajevan, I was socialized from an early age to think about the causes of the Great War – a question that happens to be one of the most studied in all of human history. I vividly recall my first primary school trip to “Princip’s footsteps” – markings embedded into the sidewalk signifying the spot from where the assassin, Gavrilo Princip, fired at the Viennese couple. We boys took turns to stand in the footprints and re-enacted the killing; the girls giggled. There was no doubt that this behaviour was desirable: with our teachers we read out the message on a nearby plaque that explained, in solemn Cyrillic script and even more solemn Aorist, how the assassin’s shots expressed the will of “our people” to be free of foreign tyranny. Is it true that Sophia was pregnant?, a classmate asked. Yes, said one teacher, but this was an accident. Princip’s bullet hit her only after it ricocheted off the car. It was intended for General Potiorek, Austria’s military governor.

Trying to grasp the meanings of “tyranny” and “ricochet” proved to be the easy part. In later grades we learned that Princip was a hero and that his “Young Bosnia” was a multi-national society of revolutionaries who fought for the unification of all Yugoslavs. The proof: one of Princip’s co-conspirators – seven teenagers armed with pistols, grenades, and suicide cyanide pills who nervously waited for Ferdinand’s motorcade that day – was a chap named Muhamed.

At home, alas, I learned that Young Bosnians were trained and equipped by a secret Belgrade-based organization called “Freedom or Death.” So was Princip a terrorist? By the time it became possible to openly discuss this question in school, Yugoslavia had started to fall apart, and the fact that one person’s terrorist was another person’s freedom fighter was no one’s idea of breaking news. Since this time, little has changed in fact: there are now two Sarajevos, and so two truths about assassinations past.

My primary school teachers also taught me how to think within a broader historical materialist framework. To understand World War I we must go back to Lenin, declared one of them in grade seven. Financial capital operating in the core needed colonies for materials, labour, and markets, and this is what ultimately led to inter-imperial wars among core nation-states and, in extension, to nationalist movements and anti-colonial violence in the periphery like ours. True, the teacher went on, socialist revolution never occurred in the core, but what Lenin wrote was that imperialism was the latest, not the last stage of capitalism. Many years later, I was amused to find out that even Eric Hobsbawm treated this point as particularly revelatory in one of his books.

I revisited the causes of World War I in earnest as a first-year university student. My international politics textbook, Joseph Nye’s Understanding International Conflict, explained it all with a brew of three levels of analysis, three types of causes, several analogies, half dozen counterfactual thought experiments, and with a dash of phrases like path dependence and overdetermination thrown in here and there. In this master concoction, some causal theories evaporated (Lenin’s, for one), others crystallized (the dynamics of the European balance of power system, nationalism, leadership complacency). Nye’s conclusion: “war was not inevitable until it actually broke out in August 1914. And even then it was not inevitable that four years of carnage had to follow.”

Things got more complicated in graduate school. The more I ventured into the philosophies behind the agent-structure problem, black swan events, pre- and post-Humean teachings on causality, fact-value distinctions and the like, the harder it became to accept not just standard textbook views, but even the most basic narrative structure of history. An example: “World War I broke out in August 1914.” Careful! The conflict may not qualify as a world war in a non-Eurocentric sense until a month later, which is when Japanese troops invaded the German settlement in Qingdao. Next, “to break out” is devoid of precision, while “August 1914” accepts the Gregorian calendar over the Julian calendar to say nothing of the Chinese, Hebraic or Islamic methods of recording the passage of time.

This was pure acadamese, of course, but it did vindicate an intuition I developed way back in Sarajevo – that all historical explanations are themselves historical. I also learned that truly multicausal explanations of the war may be rare and even impossible – I am referring to explanations that account for the complex interaction between and among causes that are both structural and agential, short and long term, intentional and unintentional, material and ideational and so on. If I could pull out a single plum from the rich pudding I ate during this time, it would have to be Richard Ned Lebow’s essay “Contingency, Catalysts, and International System Change” — it is dear to my heart primarily because of the way it revels in attention to agency, chance and accident.

Rather than turning into a lost cause, my search for the causes of the Great War remains alive, even if it is now “reduced” to an attempt to understand why people write about the past as they do. The centennial year has already seen no shortage of conversations and controversies about the war, many of which project contemporary debates about emerging powers, world trade, civil-military relations, multiculturalism and the like back to the summer of 1914. My fellow IR-ists are at it, too. Phrases uneven and combined development, perfect deterrence, and social network analysis stand for three very different recent theorizations of the origins of this particular war onset that aspire to tell us something new. This is how the academic game works: as scholars revise accounts about the past or, better yet, access new evidence, new dialectics emerge. This is why I am not ready to give up my quest: if the Great War is an object with great many functions, purposes and meanings, then paying attention to how historical interpretations of its causes shift – and fail to shift – always hold important clues and cues about our changing world.

An abridged version was published in The Ottawa Citizen today.

Good post. Planning to link it on my blog.

LikeLike

Are we not perhaps always at war in a financial sense & the dates simply denote when that constant war escalated into major shooting incidents ?

Great article.

LikeLike

Your post helps me open my mind to a different prospective. As a mid-westerner our only contact with the subject were our parents and relatives who were drafted into the World Wars to fight relatives in Germany. Even then we considered it an isolated incident with no current bearing on our lives. Unfortunately Eastern Europe (or Western Russia or even the Northern Middle East) is a cauldren that is boiling over once again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on WHAP 2014 … and BEYOND! and commented:

Let’s take another look @ WWI

LikeLike

Reblogged this on My Blog.

LikeLike

Gavrilo is not a Serbian. He is from Sarajevo which is in Bosnia and Herzegovina. I am a Serbian and this insults me and my entire nation, ’cause you americans are turning things around so, at the end, you will say that Serbia started WWI. That is so not true.

LikeLike

While the most heavy levels of Academic goes over my head, the public debate could certainly do with a bit of attention to semantics. Of course it would have been better if X million had not died in WWI, but if you were the British PM just before it broke out, it’s hard to see how it could have been avoided without something worse in turn.

Essentially I see it a bit like this: humans fight because humans fight. Stopping humans fighting takes a lot of careful socialisation and structuring, and even this isn’t always effective.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on spring13 and commented:

Great read. thank you.

LikeLike

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Entrepreneurship with twist.

LikeLike

I’d so like to read some future posts expanding your thoughts on the below quotes from your article.

” The more I ventured into the philosophies…the harder it became to accept even the most basic narrative structure of history.”

“all historical explanations are themselves historical”

“…paying attention to how historical interpretations…shift – and fail to shift … always hold important clues and cues about our changing world.”

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Making It Up As I Go Along – Trying To Think It Through and commented:

Food for thought concerning the causes of World War I.

LikeLike

Wonderful historical detail on the assassination. Interestingly, I just posted on my blog about war begetting more war… and using World War 1 as an example. Great post. 🙂

LikeLike

one main idea is that world war one, and world war two, were considered by many older europeans as one war, given that idea one might argue that humans are perpetually at war, as one other comment-er intimates, via financial means et al

perhaps our current challenge as a global community, that is climate change, will be the much needed stimulus to develop our minds beyond ‘war-think’ and re-focus on survive, thrive and explore -that is versus creating financial stimulus through human conflict

solution = create hi-tech mining and sustainable planetary systems for broad wealth stabilization

jf

LikeLike

Reblogged this on davkengfun's Blog.

LikeLike

History being written by the victors is the gist I think…

LikeLike

Good write-up by the way.

LikeLike

Pingback: Links 4/13/14 | naked capitalism

Pingback: Vote Now for the 2015 (The Duckies) IR Blogging Awards » Duck of Minerva

Pingback: The geopolitical unmoored: from exemplarity to deprovincialization | The Disorder Of Things