A shamefully-delayed commentary on Game Of Thrones, Seasons the Second and Third, since the first one went so well. As before, *great clunking mega spoiler alert*. You have been forewarned.

Recall three justifications for an analysis of pop culture politics. First, for all their superficial escapism, cultural products represent political ideas and ideologies, and do so in ways that may matter more than what we receive through the news. They are full of desires and fantasies that refract and reflect (and to some extent are themselves) real politics. Second, you can criticise the thematics of the show without hating the show. In fact you can do it while loving the show (and finding the fact of that love interesting in itself). In other words, look, I really like Game of Thrones. Moreover, that as great as comparisons with the source text can be, a TV series is a different kind of beast and is entitled to judgement on its own merits. Third, objections that “it’s just a show” don’t wash. If you’re reading this it’s because you have some sense that there are ways of understanding and being embodied in even the lowest of cultural objects (paging Dr Adorno!). That doesn’t mean that the substance of the relationship between media and politics is simple or settled, but it’s there.

Let’s start where we left off last time. It was claimed in some quarters that the plot subverts – even refutes – certain standard typical ideas about the feminine, and critiques feudal social relations along the way. So, rather than being a “racist rape-culture Disneyland with Dragons”, the many strong, complicated, agentic female roles in fact set Game of Thrones as a critique of patriarchy. But only the most one-dimensional of sexisms regards women as utterly abject. The mere presence of intelligent, or emotionally-rounded, or sympathetic female characters is not enough (and that it might be taken as inherently ‘progressive’ probably tells us a lot about contemporary gender politics). No, the issue is how a cultural product deploys some common tropes of masculinity and femininity and, with appropriate caveats about not reading every plot twist as an allegory, how those celebrate or reinforce certain orderings of gender. So a narrative which makes the family the primary unit, and which does so in a conventionally heteronormative register (twincest notwithstanding), is selling a particular idea of gender (and of community and nation and legitimate violence and…).

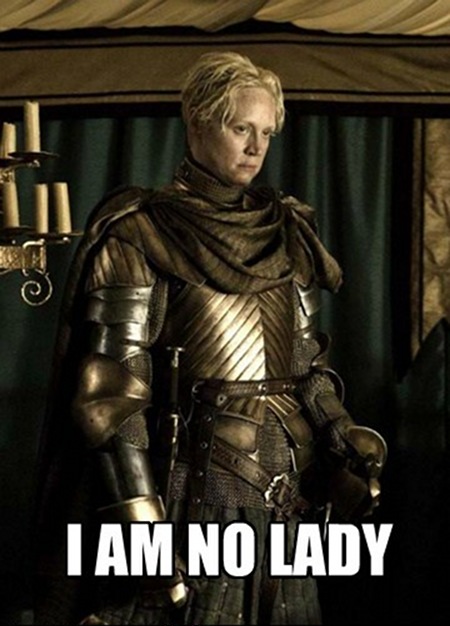

In Seasons 2 and 3, a few female figures threaten to upset the patriarchal framework. As before, there is Arya, astute, principled, fierce, and eager to promise death to her enemies. Brienne of Tarth, giant, loyal, lethal, dismissive. Ygritte, rugged, capable, sexually dominant, a hardened killer with no respect for rank (“If you ripped my silk dress, I’d blacken your eye”).[1] And yet in each case the threat is contained and wrapped in some familiar gender constraints.