Note: I decided to write this post because I got tired of trying to explain my position on discourse, reality, truth, and why Foucault is not to blame for the rolling shit-show that is US politics right now on Twitter in 140 characters. And then my 800 word blog post turned into a 4000 word essay. Sorry about that. Tl; dr version: truth is a social construct but that doesn’t mean anything goes. But the long version contains turtles and an Adam Savage gif, so do please read on…

Let me get a couple of things straight before I begin. First, I am not A Philosopher. I am not (often) a thinker of profound and important thoughts (not nearly often enough, anyway), nor do I consider the work that I do to be in the realm of philosophy, or even ‘grand theory’. I am not A Theorist either; I am, at most, a theorist with a lower-case ‘t’. I theorise, a bit, about the nature of the things that interest me and the relationships between them. It helps me make sense of the world and that’s about as far as it goes. So I am probably woefully underqualified to write this post. But here I am, because being woefully underqualified to write about postmodernism[i], and truth, and facts, and the world in general, doesn’t seem to stop a whole bunch of other people doing it and if they’re having their fun I want some. (Plus, the way you get qualified to write about Stuff is to write about it, amirite?)

Second, I have (quite unfairly, I admit), used bits of Helen Pluckrose’s recent essay on ‘How French “intellectuals” ruined the West: Postmodernism and its impact, explained’ as a sort of intellectual sparring-partner in this post, just because it offers such a full account of the charges laid at the door of postmodernism, and how this intellectual movement has affected truth, and facts, and the world in general. It’s unfair because Pluckrose’s essay is just the latest in a line of similar types of argument, and I could just as easily have chosen to respond to any of those. But I chose this essay because I am lazy and it popped up on my Twitter feed on Saturday morning and when I read it I thought: No. No more. No longer. For this, I cannot stand. So, again, here I am, to address what I see as the four key points of argument she presents in an effort to discuss the things I want to discuss about postmodernism, and truth, and facts, and so on.

1. ‘the roots of postmodernism are inherently political and revolutionary, albeit in a destructive or, as they would term it, deconstructive way’

So there are some issues here. I certainly agree that the roots of postmodernism owe much to nihilist philosophy, to radical political thought in Europe in the mid-20th century, and to the revolutionary impulses of ‘the Left’, broadly conceived (we can have the argument another day about whether ‘the Left’ was ever the coherent and homogenous political community to which these types of political discourse hark back; I suspect that just as Black women have a thing or two to say to and about White liberal feminism’s inclusivity and universality there are many who would have a thing or two to say about ‘the Left’, but that is another matter for another time…). I would certainly not agree that ‘deconstructive’ means the same as ‘destructive’ nor that postmodernism as an intellectual project is necessarily destructive (or solely concerned with deconstruction, for that matter).

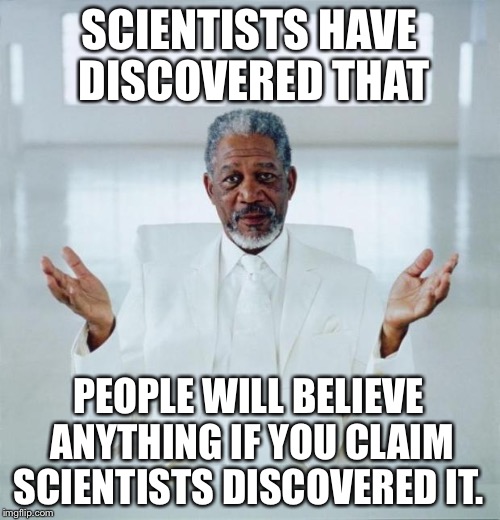

The charge most frequently levelled at postmodernism is that it has destroyed – or at a minimum seeks to destroy, for those optimist critics who are concerned but confident that the perilous postie plot will ultimately be defeated – Truth. That postmodernism is intrinsically implicated in our current and ongoing occupation of a ‘post-truth’ world of ‘alt-facts’ and wild unsubstantiated allegations, that postmodernism denies us any foundation from which to shout ‘LIES! DAMN LIES!’ in the face of such bold fictions, that claims about the ‘social construction’ of reality have led to a political environment in which anything goes.

(Source: https://media.giphy.com/media/1eKbAKgocJCta/giphy.gif)

But while I will agree that postmodernism is inherently political (though I remain unconvinced it is inherently revolutionary, for I don’t believe that postmodernism is an emancipatory project nor that it was ever conceived as such) I do not agree that the posties killed truth, and here’s why, in a series of fifteen annotated tweets I sent earlier when I was having this exact debate on Twitter a little while back:

i) The debate here is over the nature of reality but the confusion is in the distinction b/w Fact versus ‘facts’ & level of analysis.

This tweet was in response to the suggestion that I cannot claim that there are such things as facts (regarding, for example, the movement of the earth around the sun rather than vice versa) while maintaining a healthy suspicion about the status of ‘Fact’ that we attribute to certain kinds of knowledge and the social process through which that attribution happens.

ii) We – you, me, Trump, most people – operate w/in a social context we identify as reality.

Here is where I bring in the social dimension of social construction to the discussion of fact and reality.

iii) Discourse theory tells us this is a regime of truth rather than objective truth: reality is socially constructed.

To say that reality is a regime of truth, that it is socially constructed, is not to deny the existence of facts within that regime of truth. Rather, it is to acknowledge that the facts are inescapably social and therefore the fact of reality itself is socially constructed.

iv) [Aside: Don’t forget reality was flat earth and There Be Dragons not so long ago]

And also don’t forget that your reality might well be quite different to mine because the discourses that constitute it might be quite different.

v) W/in that reality there are multiple competing knowledge claims, hence the contested nature of both facts and ‘Fact’.

But even if our realities are different there are certain knowledge claims that have the status of ‘fact’, and if that is true (which I think we can agree that it is) then we share an overlapping reality in which there is such thing *as* Fact, even if we disagree about specific facts. Think of it as ‘fact-as-idea’ and ‘actually-existing-fact’: the idea(l) of Truth and idea(l)s that are true.[ii]

vi) Is ‘Fact’ an attribution that derives from an objective/material reality or can ‘Fact’ derive from discourse?

And it’s about here that the wheels start to come off for people who haven’t drunk the postie Kool-Aid. People who want to believe in the objective nature of reality (who want to believe that there just is this thing called reality to which we humans have unmediated access) can argue that reality is the foundation or basis for truth/fact. It is often assumed that postmodernist theories can’t talk at all about facts of any kind, because they want to draw attention to the ways that facts are socially constructed – discursively constituted, really – and, while they’re at it, remind everyone that the very status of Fact is itself a political, ethical, normative claim. The next four tweets need to be read as one.

vii) Your argument seems to be that if discourse theory wants to critique certain ‘facts’, they have to fall back on the objective reality of Fact.

viii) Or accept that all facts – Trump facts, alt-facts, flat-out lies – are equivalent, both politically and morally

ix) Not so, b/c that itself relies on acceptance that Fact derives its authority from correspondence w/ objective reality

x) Rather than itself being a (very powerful) regime of truth (see also Science)

The point that I am trying to make here is that I can be *suspicious* of Fact as a regime of truth and still have grounds to criticise the Trump administration for peddling outright blatant lies because they are lies within the total structure of meaning-in-use that we take to be our current reality.

xi) So w/in that context I can call out alt-facts b/c of the way the regime of truth we acknowledge as reality functions

xii) Renders them less credible than the other, actual, facts

So this is a sort of ‘turtles all the way down’ argument that posits a distinction between more and less credible claims (decided on the basis of evidence) such that some are true and some are not, because within the meta-level regime of truth in which we operate this is how Truth is decided.

xiii) But I make that distinction not by deferring to Fact as the source of authority *because it is Fact*

xiv) But b/c we attribute Fact its privilege and authority in our particular context (hence, socially constructed)

xv) Never again going to try and articulate discourse theory of reality in 140 characters at a time. LJS out.

So that was fun. And the reason I’m reporting it here is because (and thank you for bearing with me) there is nothing intrinsically destructive about this approach to life, or reality, or whatever it is that we think we are approaching here. It is not destructive to posit an alternative vision of reality, or life, or whatever, unless you believe that to challenge, or question, is to destroy, and I can’t believe that any humanist, scientist or philosopher could hold such a position – else we’d all surely be out of a job. Now, turning to the second point…

2. ‘Empirical evidence is suspect and so are any culturally dominant ideas including science, reason, and universal liberalism. These are Enlightenment values which are naïve, totalising, and oppressive, and there is a moral necessity to smash them’

Postmodernism is far from the only theory that combines empirical analysis with ontological propositions, which by definition cannot be proven through appeal to empirical evidence. This is not the same thing as claiming that ‘empirical evidence is suspect’. Honestly, show me a grand theory with an ontological proposition that isn’t self-referential: theories developed by proponents of scientific realism posit the existence of deep structures that cannot be proven but only referenced; theories influenced by postmodernism posit the ontological significance of language, which similarly cannot be proven but only referenced. But both engage extensively with that which can be observed – the realm of ‘empirical evidence’ – and interpret the world through the lenses of the ontological propositions that they posit. Foucault was profoundly concerned with medico-legal texts, government documents, and carceral practices. Derrida and Said were concerned with literature, cultural texts and film. All of them read their chosen set of empirical materials as communicative acts, asking What kinds of realities are made possible in the way that these texts claim to understand or represent political life?. It is manifestly not the case that these theorists avoided or were suspicious of ‘empirical evidence’.

It is, however, certainly fair to say that early postmodernist theorists questioned the things of which the evidence was deemed to be evidence, and questioned the things that are taken for granted in interpreting political life. These include ‘science, reason, and universal liberalism’. To be curious about how science/reason/liberalism functions in political life is manifestly not the same thing as feeling that there is ‘a moral necessity to smash them’. (We’re back to the whole destruction motif, aren’t we?) I would refute this, not least because it is not clear to me that postmodernism as a theoretical orientation posits any kind of moral necessity – in fact, and see Point 4 below – the lack of universalist moral impulse (which I would fit under the broad umbrella of ‘ethics-in-practice’) is something for which postmodernist theories are frequently criticised (although, as I explain below, I don’t think this criticism is entirely justified).

Further, science, reason, and liberalism are not the same order of thing: liberalism, as I understand it, is a theory, while the status of science/reason rests on their assumed value as modes of enquiry. Putting liberalism aside, then, the grain of truth in the critique that’s offered here is that postmodernism as an intellectual movement did indeed develop from a desire to draw attention to the ways in which that which is taken for granted assumes that status. We (in the ‘West’, an assumed Anglophone ‘we’) take for granted the superiority of rationality over emotionality, of science over religion and magic, and folklore, and other systems of belief. In fact, science has been elevated as a system of belief to the point where scientific truths have the status of unquestionable Truth and it is no longer visible as a system of belief. This is the power of science as a discourse to which Foucault was alluding half a century ago. The desire to point to this assumed value, the attribution of such a status to one mode of enquiry to the exclusion of all others, is not the same thing as saying that all truths produced within this mode of enquiry are false or themselves questionable but instead to make the rather different point that science itself functions as a particular regime of truth and that the politics, partiality, and potential problems with this ought to be borne in mind when wholeheartedly endorsing its knowledge as truth.

(Source: https://imgflip.com/i/qqitf).

Not so long ago, science, and an unquestioning fidelity to its findings, gave us eugenics. Before that, unquestioning fidelity to other belief systems had the lives of ‘heathens’ and ‘pagans’ afforded lesser value than Christian lives, and before that, Galileo met his unfortunate end for daring to question the orthodoxy. Science is, without a doubt, a powerful formation of knowledge. There is a reason that my endlessly inquisitive nine-year-old shuts up when I say ‘because science’ (which I do, because I am inconsistent, and also largely ignorant on many subjects, and I want him to go away so I can watch tv in peace. I am also a terrible parent, obviously). Any belief system with that kind of power does deserve investigation. I believe that we should enquire when, where, and how, science is deployed to discipline knowledge and meaning, and I believe that this is what Lyotard was getting at when he posited ‘a strict interlinkage between the kind of language called science and the kind called ethics and politics’ (1979, p.8, apparently, as quoted in Pluckrose’s essay). The nature of that interlinkage is, to my mind, the inescapably political and therefore ethical nature of scientific knowledge. With that in mind, on to the inevitably political and therefore partial nature of knowledge as a thing…

3. ‘“If I judge that tennis balls do not fit into wine bottles, can you show precisely how it is that my gender, historical and spatial location, class, ethnicity, etc, undermine the objectivity of this judgement?”’

This quote, attributed to Erazim Kohák by way David Detmer, exemplifies what I consider to be a conflation of various elements of postmodern thought in a particularly unhelpful way: here there is the allegation about anti-empiricism; there is the assertion that posties care too much about identity, and subsequently appeal to a highly individualised ‘subjectivity’ rather than adhere to a scientistic ideal of objectivity; everywhere is the implicit argument that postmodernism’s dealing with truth are faintly ridiculous.

For one thing, tennis balls do fit into wine bottles. Give me a good pair of scissors and half an hour and I’ll show you how. So the answer to the question of whether tennis balls fit into wine bottles is in fact conditioned by how you approach its investigation (the parameters of the investigation, the tools you have at hand, and so on). But the question of whether tennis balls fit into wine bottles is not really what’s at issue here. This anecdote is used to challenge relativism, not just the anti-empiricism of which postmodernism is accused and which I have dealt with above. The relativism here is perceived in the idea that ‘gender, historical and spatial location, class, ethnicity, etc’ affect how we make judgements about the world. There are a number of problems with this argument. First, the idea of standpoint epistemology – that your identity affects what/how you can know – was not initially advanced by postmodernist theories. You can blame the posties for a lot, but not this. Unless we’re reclassifying Marx as a postmodern theorist, which is a rabbit hole down which I am seriously not going to tumble in this already over-length essay.

Second, this argument falls prey to the conflation I allude to above, which confuses fact-as-idea with actually-existing-fact. ‘Objectivity’, in the above quote, is a quality attributed to the judgement (in this case, that tennis balls don’t fit into wine bottles). So the reader is being asked to endorse the judgement (that tennis balls don’t fit into wine bottles, an actually-existing-fact within the parameters of this exercise) and through that endorsement reach the conclusion that the judgement is objective (and therefore that the fact-as-idea proposition holds). It is actually the latter proposition with which the criticism is concerned, as I understand it, because what the author is really afraid of is that fact-as-idea as a proposition is undermined by the acknowledgement that different people have different approaches to, and understandings of, the social world – we might say their understanding and interpretation is relative to their positioning. But as I think I have outlined above, you can acknowledge that knowledge is relative – and therefore that judgement/truth/actually-existing-facts are relative to social context – without having that acknowledgement leave you in a position from which you can make no political or ethical claims at all.

Postmodernism is not, contrary to Point 3 above, ‘suspicious’ of empirical evidence, but rather is alert to the ways in which evidence is marshalled in service of particular sets of argument and the way that ‘common sense’ ideas are invoked in order to foster and perpetuate particular formations of knowledge such that they become regimes of truth. But this means that posties, at least as far as I am aware, would use evidence to determine the credibility of a series of knowledge claims just like everyone else, while maintaining fidelity to the assumption that the credibility is contingent and conditional on the particular historical, social, and political context, as is the meta-level idea that ‘evidence’ is the determinant of credibility (i.e., proceeding with the belief that actually-existing-facts are conditioned and produced by the fact-as-idea proposition in contemporary politics) (i.e. this thing is true because science).

4. ‘Our current crisis is not one of Left versus Right but of consistency, reason, humility and universal liberalism versus inconsistency, irrationalism, zealous certainty and tribal authoritarianism’

There is a particular irony in criticising certainty with such… certainty, not to mention a lack of humility in the assertion that what ‘we’ need is a total, consistent, my-country-right-or-wrong, commitment to universal liberalism. The point that I have been trying to make – the point that I believe postmodern theorists were trying to make – is that certainty is the enemy of critical thought. And I know there are nine million ways to define ‘critical’ and all of them are unsatisfactory, so let me return to where I started when I began to understand that there was an already-existing vocabulary that would help me explain how I see the world and this vocabulary could be found in the University library filed under ‘F’ for ‘Foucault’.

What I understood when I read Foucault for the first time (and it took me an embarrassingly long time to read my first book from beginning to end – it was History of Sexuality Volume 1 – and I confess that I threw it across the room many times in frustration) was that we – our subjectivity, our agency, our relationships to the things in our world and those things of which we speak – are constituted in and through discourse. There is no space outside of discourse from which to speak that is free from the power that produces certain possibilities of speech and action (including the labelling of this thing ‘true’ and another thing ‘not true’) and precludes other possibilities. We can have the discussion another day about Foucault’s rendering of subjectivity, whether his later musings on agency are enough to redeem him in the eyes of those who don’t wish to posit a subject wholly determined by and in discourse, but for now the point I wish to make is that discourse is what there is and therefore that is what I – along with others so inclined – study. To invoke Laclau and Mouffe, this is not to answer the question of whether a world exists independent of discourse, but rather to acknowledge that we cannot possibility apprehend such a world even if it were to exist, and so to turn to the study of that which can be apprehended (discourse, in case I haven’t made that clear).

But the important thing about discourse is that it is always in the process of reproduction. Discourses are neither stable nor immutable (though some are more stable and mutable than other) and always require reproduction, which is where contingency again features in a discourse theory of truth. Discourses are highly consistent (because they are, after all, structures of meaning-in-use, and it would not be good at all if discourse on a given topic were not so consistent as to provide a shared understanding of said topic) but they are not fixed, they are always in the process of becoming and change is therefore not only always possible but actively part of the process of meaning-making that is discursive reproduction. There is a logic to discursive reproduction, there is nothing irrational or authoritarian (zealous or otherwise) about this process, and underpinning this view of knowledge is the fundamental precept that all that is could be otherwise. If this does not lead a scholar down the path to humility, then I don’t know what would.

When it comes to having, as my granny would have said, the courage of my convictions, I suppose I am quite certain that discourse theory offers me a way to identify not only how things got to be the way that they are, but also how the way things are can be contingent on very particular configurations of power and authority, and therefore how the way things are need not be the way things will be in the future. Might this be wrong? Absolutely. Might there in fact be a foundation beneath the turtles after all? Of course. But in the meantime, I need a way to make sense of the world and a theoretical orientation that will allow me to level critique at the manifest injustices, inequalities, and outrages visited upon people across the world, whether in the name of religion, science, liberalism, security, or development. To me, this is the broad, shared, normative project of ‘the Left’, and we do ourselves and each other a disservice when we dismiss or disavow efforts at engaged critique because somebody once said something peculiar about giraffes and ants.

Endnotes

[i] So, here is a thing about terminology. Most of the essays I have read on this topic target ‘postmodernism’ but this is not a term I use in my own writing. In fact, I have spent a little bit of time explaining why I would identify my work as poststructuralist in orientation rather than postmodernist, because I, like many others, came to understand the ‘post-‘ prefix through literature and linguistics, rather than art and architecture where the designation of postmodernism is more common. Describing my work as poststructuralist emphasises its lasting connections and intellectual debt to structuralism and the work of Ferdinand de Saussure et ses amis. That said, I use postmodernism in this essay because a) that’s the description that has purchase in contemporary debates and b) no one really cares about the difference other than people who already know what the difference is and this essay is already a bazillion times too long, which is why I have buried this discussion in a footnote.

[ii] This formulation owes a debt to Kieran Healy’s very brilliant, very sweary, essay on nuance.

Dear Laura,

I thoroughly enjoyed this rant (although I was supposed to be reflecting on the reflections of rwanda, twenty-three years after a genocide, that was also civil war and indeed, a profundly regional, or even ‘world’ war… but not one with a Americo-European referential point… and also an event that was energised by democratic practices of ‘Hutu power’ and has not been genocidal under conditions of autocracy… An event/place where empirical questions such as the official death toll remain political).

While reading your piece, I also felt a bit negligent as a ‘dad’ because my 10 year old son was shunted away to play chess with his mum while I became embroiled in your essay. I do hope i have not created too much gender confusion for him.

Like you, I have thrown most of the iconic posties across the room. I suspect that is a common trait for those who persevered with them.

Like Baudrillard, I feel that we live in a time where “we” have come resent mere facts and truths because they interfere with our cherished representations. I tried to explain this idea to a couple of students, but they were not interested, at least not while they stood face to face communicating to each other on messenger.

Must go now, the finale of RuPaul’s Drag Race beckons…

LikeLike

I can’t resist but point out that the whole “reality was flat earth not ago” is a long-debunked myth I’m surprised to see in this intellectual essay! There might have been a bit of collective idiocy in the Dark Ages, but we’ve known about a round earth since Ancient Greece, and science has always been clear on the subject.

LikeLike

As a slightly longer reply – I enjoyed the piece, not quite as much as your other posts (maybe because mention of Foucault makes me slip into a coma), but I did, so I hope you don’t mind my criticism 🙂

The biggest issue I feel with postmodernism is when observing it as it occupies itself in a particular time i.e. ours. In a world of alt facts, postmodernist discussion taking over a good portion of the left only dilutes the issues – not just that, worse, they complicate them, degrading the arguments. Maybe not to a handful of academics, but they do to Joe & Jane Public.

You try fighting against counterfactual statements and total, threatening bullshit while also drawing upon postmodernism statements of “yes, the facts I’m trying to convince you with.. well yes, they exist in their own regime of truth… no not like alternative facts…” – now remember you’re having this conversation not with a fellow postmod academic but a layperson.

You’re not convincing with heavy essays aimed at a very small preaching-to-the-choir selection of peers – (and even if you were, to what benefit?) You’re arguing on social media, you’re talking to a friend or stranger in person. The argument is a grassroots one far more than an academic one.

Maybe the people you discuss with went to uni, maybe they didn’t, it doesn’t matter, they’re either already on your side or you’re losing them. The argument is still being needlessly complicated and diluted. Postmodernism is something that I feel needs to stay as caged within hardcore academia as possible until a much better hold is gotten of society’s worse impulses and we live in a more truthful society (if that ever happens) – even if said truth does exist in a “regime”, as long as it isn’t a toxic, dangerous one. And I don’t think empiricism is toxic – I think science is the best tool we have and are likely to ever have for examining factuality.

We can get all abstract and philosophical about reality, but we still have to live in it – and science has proven its mettle endlessly when it comes to practical usefulness. Ccountless people are not always so fortunate as to be able to philosophise about the state of their existence, and the nature of suffering and power structures, and objective truths are required both by them as a means to live and fight, and by others in order to support them and challenge that which directly challenges them.

Basically, one thing at a time. I’d struggle at this time to see what practical gains postmodernism is achieving these days, what it is contributing to the struggle of the marginalised and oppressed in terms of what they can actually observe and experience for themselves, rather than acting as an accidental ally to the worlds of post-truth and alt facts. It seems we like to strive for the highest, abstract, lateral forms of thought and argument while we don’t even as a population (nation or world) have a grasp of the most basic and fundamental.

LikeLike

Add science denialism and opinion-as-fact as the accidental allies postmodernism cultivates/allows to foster 😛

Sorry. I’ll stop now. No doubt I’ve completely missed the point.

LikeLike

Pingback: Spectacles of death – Stories of Conflict and Love

Pingback: Getting Used To Ourselves – and more words…

Pingback: How French “Intellectuals” Ruined The West (2017) | Foucault News

Your arguments supporting the idea that postmodernists use empirical data, showcase a misunderstanding of what the scientific method is, a misunderstanding of which postmodernism is also guilty. The most reputable of sciences make predictions and then test them with data. Postmodernists observe data and make theories but never test them. Merely observing correlations such as sexist public discourse and poor educational outcomes for women is not science nor a credible endeavor of any other name. Especially when the observations are made in a non-quantitative way.

LikeLike