A guest post in our resilience and solidarity symposium from Rhys Kelly and Ute Kelly. Rhys is a Lecturer in Conflict Resolution at the Division of Peace Studies, University of Bradford. His work currently focuses on the pressing challenges posed by ecological crises (including climate change) and resource depletion (including ‘peak oil’). Retaining a long-standing interest in (peace) education, Rhys’ work is now broadly concerned with investigating what kinds of individual and social learning are needed and possible in the context of increasing global insecurity, which might support just and peaceful transitions to more resilient, ‘sustainable’ communities. Ute is a Lecturer in Peace Studies at the University of Bradford. Her current research interests arise from the intersection of two areas that she has been interested in – the theory and practice of participatory engagement processes (particularly dialogue and deliberation), and the emerging interdisciplinary field of social-ecological resilience. Ute is interested in exploring the communicative and collaborative dimensions of resilience, the relationships between people and the places in which they find themselves, and approaches to enhancing resilience at different levels and in a range of contexts. She also teaches a module on ‘Peace, Ecology and Resilience’ within the BA in Peace Studies, encouraging students to explore the meanings, uses and limitations of ‘resilience’. Rhys and Ute are jointly engaged in exploring the meanings of ‘resilience’ on the ground, particularly for people who have been trying to engage with the converging ecological, economic and energy crises facing us today. Relevant recent joint publications include ‘An Education in Homecoming: Peace Education as the pursuit of Appropriate Knowledge’, Journal of Peace Education (2013); and ‘Towards Peaceful Adaptation? Reflections on the purpose, scope, and practice of peace studies in the 21st Century’, Peace Studies Journal (2013).

Those who responded:

engaged with resilience,

thoughtfully active.

‘I want you’, she said,

‘to ditch ‘resilience’ now’.

How, then, to resist?

Part of a sequence of haikus about ‘10 days in September 14’ for a collective zine, these two fragments are an attempt to convey Ute’s experience of the workshop on ‘Political Action, Solidarity and Resilience’. The first tried to describe the people who responded to a survey we had created to gather reflections on ‘resilience’.[i] The responses to our survey were thoughtful and reflective, and most came from people who are critical of the status quo and trying to respond to a set of crises that includes climate change and the degradation of ecosystems, energy depletion, austerity, conflict, inequality and injustice. Interestingly, many of our respondents appreciated the opportunity to reflect on their own understandings of ‘resilience’, on the contexts in which they had seen the concept appear, and on its strengths and limitations.

The second haiku poses a question that emerged from some of the discussions at the workshop itself – in particular, a tendency on the part of some of the contributors to dismiss the idea that ‘resilience’ might be a helpful concept, to conflate a focus on ‘resilience’ with neoliberal agendas, and/or to construct ‘resilience’ and ‘resistance’ as mutually exclusive concepts.

Such a construction, we feel, is too narrow, too caught up in looking at how ‘resilience’ has been used in some (not all) academic and policy discourses, and too dismissive of genuine attempts to grapple with ‘the fragility of things’, with a real sense of converging crises. This is a genuinely difficult context, with no easy answers. We think it is important to take this seriously, to read people’s responses sympathetically, and to introduce some humility into related academic debates.

What follows is a set of preliminary themes that have emerged from a first reading of our survey responses, from related conversations we have had with a range of people, and from our own experiences. These themes indicate some of the ways people are using and interpreting the concept of ‘resilience’ in finding responses to questions presented by a context of fragility, crisis, distrust, disillusionment, inequality, violence and abuses of power: What does it mean to live in this time, and how might we keep some sanity? What do we value, and what does this mean for how we (inter)act? What does it mean to develop and sustain a sense of agency in this context? What kinds of political projects actually make sense against this background? Where do we put our energies?

I. Hope and agency

Many of the people who responded to our survey commented on the potential of ‘resilience’ to generate some hope, to draw attention to positive assets, capacities and possibilities, and/or to strengthen their sense of connection with others. One respondent, for example, said in response to our question about what had been helpful about the concept of ‘resilience’ that ‘it gives me hope which I had almost lost for the past 10 years’. For another, ‘it provides the energy and space to not feel overwhelmed by circumstances or challenges’.

These understandings clearly relate to definitions of ‘resilience’ that emphasise the ability to ‘bounce back’, and that see ‘resilience’ as the positive end of a spectrum that includes different levels of vulnerability. In a context of increasing fragility and vulnerability, when “it’s mighty hard right now to think of anything that’s precious that isn’t endangered“, thinking about what, if anything, might be done to enhance their resilience seems a reasonable response. But is this hope as complacency, as an avoidance of more challenging questions? Is it, for those of us who are worrying about the future but not yet feeling immediately threatened, a bit too easy? Does a focus on resilience deflect attention to the recognition that, as Naomi Klein puts it, ‘we’ – ‘our individual bodies, as well as the communities and ecosystems that support us’ – ‘break too’? We are not sure.

It seems to us, though, that talking about hope, empowerment and positive possibilities is helping people to find a sense of agency that is otherwise threatened. In this sense, engagement with resilience seems to be driven less by the temptation towards retreat than by the attempt to reclaim a sense of agency, of being proactive in difficult circumstances. As one respondent put it, “[the concept of resilience] often gives me the energy to keep going. Sometimes it makes me change course, and take risks that I otherwise would not”.

We also suspect that engaging with resilience may be one way of responding to the existential questions raised by ‘the fragility of things’ with less hubris, resentment or ‘studied complacency’, fostering instead an ethos of care for people and the world. The sense that a resilience framework offers some hope and a sense of agency is further strengthened, for some of our respondents, by a sense of connection to a wider community of people (perhaps particularly for those for whom the concept has been closely associated with the transition movement):

I find it very encouraging to know that there are many other people all over the world for whom this concept and way of life is also important. Networking, support and sharing ideas is a key part of resilience.

We will come back to the ways in which ‘resilience’ can foster experiences of connection. First, we consider issues to do with scale and place.

II. Scale and place

Often, and understandably, the focus of efforts to enhance resilience is placed on relationships and places that people feel personally connected to. As Connolly puts it, “our identification with life – our tacit sense of belonging to a human predicament worthy of embrace – is partly rooted in the identities, faiths, and surroundings that already inspire us”. The recognition of affection for particular places as one motivation for getting involved in both resilience and resistance raises interesting questions about the scales at which engagement with complex systems becomes meaningful.

Part of the motivation for scaling down comes from the recognition that even small systems are highly complex, often exceeding our abilities to intelligently work with them. The level of local communities, for example, might represent a scaling down for many, particularly perhaps for scholars of political science and international relations. Yet in our own experiences and in critical conversations with people engaged in local initiatives, we have found that even at this level, the idea of building resilience can feel daunting. For instance, initial efforts to get a transition initiative going in Bradford felt much more overwhelming than empowering, with members eventually putting their energy into the more manageable (but still considerable) project of a community farm. Often, it seems to be smaller, more particular, or sometimes shorter initiatives that engage people’s interest and enthusiasm. There is a moral dimension to this question of scale too. As Wendell Berry suggests, “we must not work or think on a heroic scale. In our age of global industrialism, heroes too likely risk the lives of places and things they do not see. We must work on a scale proper to our limited abilities.” Building resilience locally therefore may be pragmatic, but can also involve a conscious decision to forge a responsible relationship with place.

III. Connection

Another important theme that emerges from our survey is that a resilience framework encourages people to make connections between multiple issues, to move away from ‘working in silos’. The tendency of ‘resilience thinking’ to emphasise connections may help to keep ‘the bigger picture’ in mind even as people focus on the here and now, and thus may facilitate building solidarity across multiple issues and constituencies. One respondent, for example, says that resilience “has given me a new angle with which to approach concerns I’ve had for some time; public libraries, climate change, the commons, technology”.

As well as connections between issues, resilience can also put ‘more weight and emphasis on building connections [between people] during times when we aren’t facing the external shock and also to help think about the value of connections that could hold strong whatever the shock’. In thinking about local level resilience, such connections do not necessarily imply agreement on values or politics. As Sharon Astyk has observed, creative adaptation to “a world where most of us are poorer [and] less secure” also means “work[ing] with people we once did not need”, with “people we did not choose”. This point is interesting in relation to the framing of solidarity, resistance and political action: Is solidarity necessarily ‘explicitly political’? Or can solidarity also mean an effort to connect even across political and other differences? If we accept, as Connolly suggests, that ‘we inhabit an entangled world’, is ‘the best hope … to extend and broaden our identities, interests and ethos of inter connectedness’, to cultivate generosity?

On a related note, it is worth noting that at a pragmatic level, several of our respondents observe that resilience has been a concept that has allowed them to express their concerns and values in ways that resonate more easily with others than alternative framings. For those concerned with inclusive and creative responses to change, then, the mainstreaming of ‘resilience’ is not necessarily a problem – and again, we would emphasise that recognising when it might be ‘instrumentally useful’ to talk about ‘resilience’ is compatible with critical reflection on problematic uses of the term.

And there are, of course, also critical questions to be asked in this context: When does an emphasis on inclusion, connection and partnership become counterproductive? Is resilience, after all, driven by “a conservative, indeed pacifying rationality of governance”? Does “coming to terms with fragility … undercut the political militancy needed to respond to it”? As Connolly suggests, this is ‘a living paradox of our time to engage and negotiate’.

IV. Resistance

For many of our respondents, their engagement with resilience is informed by a sense of the unsustainability and dysfunction of economic and political systems, and their negative implications for social and ecological systems. The dominant feeling is more of a distrust in, and critique of, current economic and governance systems than uncritical acceptance of them or the willingness to fit within them. On the one hand, this comes out in the reservations that people expressed about (some of) the uses of resilience, and which resonate with critiques of ‘resilience from above’. A number of comments express worries about the co-optation and use of the term by governments, business, and neoliberal institutions, about understandings of resilience as the maintenance of a problematic status quo, about a focus on resilience at the expense of a critique of inequality and injustice.

On the other hand, and often at the same time, people are also using ‘resilience’ as a way of expressing their critique of wider systems, and as a framework that has helped inform their responses. The following comments from respondents are examples of how ‘resilience’ can inform systemic critique:

I have been arguing for many years that current systems are not sustainable and that we need to make changes in pretty much everything. I have found it hard to stomach many of the changes in modern Britain. I believe in fairness; taking care of those who cannot take care of themselves; renewable energy; sustainable food growth; the need to move away from money as the centre of everything; people having more time for themselves, their friends and families… I think it’s all part of resilience.

it has radicalized me, seeing how our industrial civilization has always traded away resilience in favor of the economics of scale, ever greater efficiency, productivity and private profits. Private property rights are an example of efficiency but not resilience

So far, it connects/intersects – politics, culture, community, resources. It’s political. It’s flexible.

For many, resilience includes self-reliance. Importantly, self-reliance, in this context, is not understood as a falling-in-line with an individualistic neoliberal ideology but rather as a practical way of expressing resistance. A dichotomised framing of ‘resistance versus resilience’ is thus misleading.

The relevance of resilience for resistance, moreover, goes beyond resilience as building positive alternatives to the status quo. The resilience of resistance and activism themselves is an important theme that provides a counterweight to the idea that ‘resilience is by definition against resistance’. For some, an engagement with resilience is motivated precisely by the question of how to sustain resistance.

Drawing on resilience frameworks and neighbouring sets of ideas can shape and enhance activism and resistance in several ways: thinking carefully about how the human energy that goes into collective action can be valued and sustained, designing movement structures that are modular rather than overly centralised, valuing diversity, and preparing for repression. The idea of resilience as a helpful way of sustaining the personal and collective energy to engage in agency for change is also expressed by people who are working within systems they have little control over (e.g. in public sector organisations) but are critical of the wider structural pressures and constraints within which these are embedded. Something we have learned from conversations with too many people who have found themselves in such situations is that sustaining resistance in such settings requires a high degree of personal resilience, and solidarity needs relationships that are resilient to stress. In situations where people are feeling vulnerable and fragile, these forms of resilience are not easy to maintain. And yet it is the very sense of shared vulnerability that generates the need for both solidarity and resistance.

Concluding Thoughts

It does not seem, then, that the spread of ‘resilience’ to a variety of contexts, and particularly its use in ways supportive of the status quo, necessarily undermines its potential to inform critique, resistance, and the impetus to build alternatives to unsustainable and inequitable systems. People are capable of critical and reflective engagement with the concept, and of distinguishing between helpful and problematic uses!

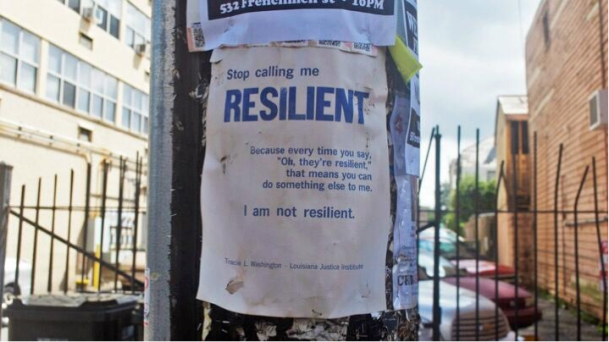

One distinction that has emerged from our survey and our own reflections is that the perspective from which people encounter ‘resilience’ really matters. There are significant differences between claiming resilience as a tool for thinking and/or a positive personal or collective attribute on the one hand, and experiencing it as a judgement that is made about individuals or communities.

I think that resilience is something that we can only assign to ourselves. It should not be directed at us by others, especially not in a passive aggressive way. We come to it ourselves.

I first came across it in training provided to staff undergoing a bruising restructure, when useful as I found it, it seemed like the smile on the face of the tiger. A bit like ‘I’m going to throw these sharp heavy rocks at you and at the same time teach you how to jump out of the way’. Well. Just don’t throw the rocks?

we need to be alert to the fact that the introduction of individual resilience into our parlance does offer greater opportunity for pathologisation than previous ways of talking I think.

There is, then, a need for continuing personal and collective reflection on whether, and in what contexts, putting the emphasis on resilience may stimulate or marginalise engagement in resistance, on how and when it engenders solidarity, and on the differences between, as one participant put it, ‘selfish resilience and resilience for humanity’.

The important thing is that these questions are being raised, discussed and reflected on. Many survey respondents finished with a thank you for the opportunity to engage in this reflection. In responding to our question about what had been helpful about resilience thinking, one survey participant named ‘the debate itself. It is a kind of discussion that should never end from now on’. So instead of a conclusion to what remains an open project, this is a thank you to all those who responded, and an invitation to continue the discussion.

[i] We initially chose to focus on a cluster of networks – the Transition Towns network, Permaculture, the De-Growth movement, the Post-Carbon Institute, etc – who share a broad set of assumptions about the likely impacts of climate change and energy insecurity. We expected, as participants ourselves in these networks, that this would be a useful and relevant starting point for inquiry. In addition, we also connected with a network of academics and practitioners involved in peace/community-building/dialogue work in the UK. As we started receiving responses, and having conversations with people, we also followed up some additional links that emerged from people’s responses (e.g. BoingBoing, Sustaining Resilience). So far, this has generated 90 responses. For more on the survey – or to participate! – see this link.

Resilience is a concept greatly used in psychiatry and in the recovery movement. The first part of your paper really speaks to this, especially the notion of bouncing back. In psychiatric or other contexts that involve suffering, I would argue that it is this suffering that teaches the lesson of resilience. Is it true I wonder in the context in which you argue it here too?

LikeLike

Pingback: Why We’re Not Ditching Resilience Yet… | Equities Canada

Pingback: Why We’re Not Ditching Resilience Yet… | mollyellarae

Pingback: Why We’re Not Ditching Resilience Yet… - Resilience