A guest post by Amit Julka and Medha.

Amit is a PhD student at the Department of Political Science at the National University of Singapore (NUS), and he is working on India’s engagement with Afghanistan from the perspective of Indian identity formation. Previously he worked as a media specialist with the US Embassy in New Delhi and at the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA), New Delhi. He holds an M.A. in South Asian Area studies from SOAS, and is a computer engineer by training.

Amit is a PhD student at the Department of Political Science at the National University of Singapore (NUS), and he is working on India’s engagement with Afghanistan from the perspective of Indian identity formation. Previously he worked as a media specialist with the US Embassy in New Delhi and at the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA), New Delhi. He holds an M.A. in South Asian Area studies from SOAS, and is a computer engineer by training.

Medha is a research fellow/doctoral student at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg. Her research focus is on the role of Islam in India’s identity and foreign policy. She previously worked at the IDSA, and also as a journalist in India, Germany, the Netherlands and Canada. She holds an M.A. in Media Studies, jointly from Aarhus and Swansea Universities.

Medha is a research fellow/doctoral student at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg. Her research focus is on the role of Islam in India’s identity and foreign policy. She previously worked at the IDSA, and also as a journalist in India, Germany, the Netherlands and Canada. She holds an M.A. in Media Studies, jointly from Aarhus and Swansea Universities.

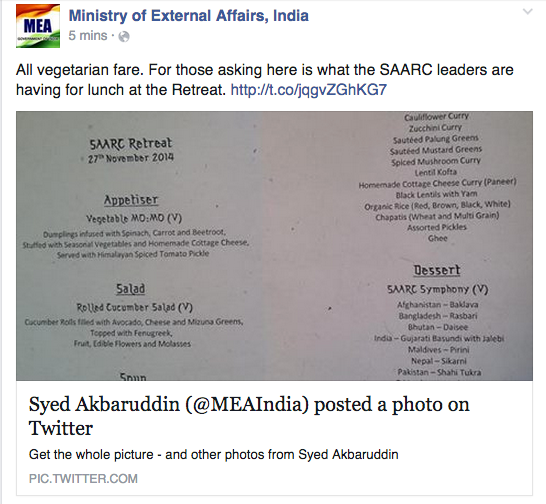

Among the many anodyne reports from the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) summit held in Kathmandu recently, there was a curious piece of news: an article about how the Indian Prime Minister was being served ‘simple vegetarian fare with less spices and oil’ while his Pakistani counterpart was enjoying ‘halal meat dishes’ during their respective stays in Nepal. The next day, on social media, India’s Ministry of External Affairs posted a photograph of a menu with the caption ‘All Vegetarian Fare. For those asking here is what the SAARC leaders are having at the Retreat.’

While it may be routine for the media to report about the dishes served during meetings and summits, this emphasis on Modi’s vegetarianism—and his apparent success in making sure all the leaders consume vegetarian food, at least at the Retreat—is particularly noteworthy. Especially when the fact that Modi was fasting for Navratri during his visit to the US was also equally publicised. Was this an attempt at burnishing Modi’s image as the Hindu Hriday Samrat within India as well as the increasingly vocal Indian or more precisely, the Hindu community abroad?

There is a definite hierarchical ordering of food in Hindu thought. At the top, in terms of the moral order, sit sattwik foods: vegetarian, non-spicy, simple—ideally involving little or no harm to the source of the food. These foods are supposed to result in clarity and equanimity of the mind. Then there are rajasik foods or stimulant foods that supposed to produce mental restlessness, followed by tamasik foods which are supposed to be harmful to the mind and body. Meat falls into this last category.

Inherent in these categorizations is an element of morality. Consumers of rajasic and tamasik food are thought to be more subservient to their gross urges, while a sattvik diet is associated with spiritual purity. It is important to add here that these categorizations are not considered rules within Indic philosophy—unlike the proscription against pork in Judaism/Islam—but rather serve as norms for the upper castes. Select Brahmins such as those from Kashmir and Bengal, for instance, continue to enjoy the quasi-illicit pleasures of meat eating. In the case of the Kshatriyas, the warrior caste, consumption of meat is even considered necessary for them to carry out their dharma or duties. These norms, thus overlap—though not always neatly—with caste categories, and sometimes aspiration to social mobility takes the form of adoption of the norms of the upper castes. Even renowned anti-corruption crusader and social reformer Anna Hazare’s attempt to transform a village in Maharashtra involved persuading lower castes to abstain from ‘impure’ practices such as meat consumption. The hegemony of vegetarianism can be ascertained, for instance, from the term ‘non-veg’, which refers to meat as well as the person who consumes meat. Meat eating in India is thus defined in negation to the norm of vegetarianism, lacking an independent identity of its own.

Muslims, Christians and Adivasis, who fall out of this moral universe, are referred to by the rather derogatory term mleccha. Similar in a sense to the term barbarian, it encapsulates connotations of a superior, clean and spiritually pure us and an unclean, inferior, spiritually degraded them. This idea of food as marker of difference—of corporate identity—in the sense of defining who belongs to the in-group and who doesn’t has found expression in recent years in the increasing imposition of vegetarian only residential societies —primarily in Mumbai and Gujarat.[1] The vegetarian rule here serves as a politically correct tool for exclusion of those considered undesirable, namely Muslims, Christians and catch-all others.

In the political sphere, this delineation of boundaries is exemplified, for instance, in the Hindu nationalists’ praise for ex-President Abdul Kalam. It is not only his contributions to science and India’s defence program that are highlighted, but also his simplicity and acceptance of vegetarian diet—underscoring the point that he is our kind of Muslim. On the other hand, prior to the hanging of Ajmal Qasab, a Pakistani national involved in the 26/11 terrorist attack in Mumbai, Hindu nationalist discourse on the internet often castigated the Congress government for going easy on him and feeding him biryani—a rice and meat preparation commonly associated with Muslims in the subcontinent. Thus, while Kalam’s vegetarian diet is conflated with his simplicity and industriousness, Qasab’s consumption of meat is equated with his wickedness and his militant and aggressive nature.[2] Meat thus becomes a litmus test to judge who is ‘our’ kind of Muslim and who is not. The consumption or non-consumption of meat as a yardstick for patriotism isn’t restricted to Muslims alone. Track II diplomacy delegates from India—usually berated as peaceniks—are often blamed for compromising India’s agenda by letting themselves be seduced by the ‘meat laden hospitality’ of their Pakistani hosts.[3]

This sense of illicitness associated with meat-eating—many people eat meat, but not at home or in the presence of parents—also represents a kind of desire and envy. This can be gleaned, for instance, from the fact that jokes that deal with taboo topics such as sex are referred euphemistically as ‘non-veg jokes’. The desire/envy of meat is not only a matter of taste, but also towards the supposed benefits that it bestows. Thus, even a staunch vegetarian like Mahatma Gandhi had a brief stint with eating meat as a teenager so that he could be as ‘strong’ as the British.[4] Later, however, Gandhi looks back at this brief fling as a temporary detour from the path of righteousness.

In this context, the emphasis on Modi’s ‘simple’, ‘less spicy’ vegetarian diet carries with it connotations of his supposed moral uprightness, simplicity, and single minded devotion to India’s interests. Unaffected by temptations of the flesh—dietary and otherwise[5]—Modi thus emerges as the ideal karmyogi[6] of the Gita, a noble warrior fighting the cause of Mother India. Barring the militant undertones, it also resonates with Mahatma Gandhi’s conception of a virtuous man, standing on the twin pedastals of vegetarianism and celibacy, untainted by desire. That this characteristic of Modi acquires special salience during his diplomatic tours is also critical for constructing this identity. The contrast between Modi’s moral uprightness and dedication as symbolized by his vegetarian diet and the habits of other leaders—Nawaz Sharif’s predilection for meat, for example—can be easily conveyed to the domestic audience.

Both the specific mention of Nawaz Sharif’s meat eating in general, and the emphasis on the meat being halal is relevant here. Nearly all leaders whom Modi has met till now, in South Asia and otherwise, have been meat eaters. However, the singling out of Nawaz Sharif, and the emphasis on his Muslimness via the prefix halal conveys an attempt to delineate the Self versus the Other. Nawaz Sharif’s halal diet is thus juxtaposed with Modi’s vegetarianism, which by extension become symbols for the opposition between India and Pakistan. This also serves to highlight the precarious position that Indian Muslims hold as internal Others. Also, the fact that the presumably halal diets of Bangladeshi, Afghan and Maldivian delegates were not mentioned does give credence to the notion that for India, some halals are more halal than others.

Also noteworthy is that the release of the copy of the all vegetarian fare at the SAARC retreat by the MEA: is it a subtle suggestion that our virtuous vegetarian leader was able to prevail—morally and otherwise—over other presumable meat eaters? On its part, Nepal’s choice of an all vegetarian fare for the banquet too could perhaps be construed as an attempt to highlight the shared Hinduness that binds India and Nepal, a notion that would surely resonate with the current dispensation in India.

The Indian Prime Minister’s conduct outside India thus becomes a means to construct a specific kind of India, with Modi exemplifying an ideal type of an Indian. Modi is the best possible leader for India because he represents the best of what it means to be Indian. This is contrasted, in this particular instance with the stereotype of a Pakistani as embodied by Nawaz Sharif. The leader and the nation are thus mutually constituted in this discourse. The Othering of Nawaz Sharif and thus Pakistan based on dietary preferences borrows from, and reinforces the larger discourse of the Muslim Other within India. India’s external interactions become a field for defining what it is, or is ideally supposed to be, domestically.

This conflation of an ideal Indian with an ideal Hindu has troubling consequences for the delineation of minorities in India. It is as if there is a hierarchy of Indianness and some are more Indian than others, harking back to the Hindu Right’s assertion that all minorities are welcome to live in India as long as they accept that they live in a Hindu nation. The premise being that only Hindus can be entrusted with the project of constructing and defining the nation. The Other here is not considered completely external to the nation, but a second class citizen who cannot be entrusted with this noble task. The Muslims further bear the burden of being ‘related’ to an external antagonistic Other.

In making these interpretations, we may be accused of reading too much from an innocuous detail. However, the very act of inclusion—or omission—and framing is political and endowed with meaning within a contextual realm. When it comes to politics, there is no such thing as a semantically free lunch.

Notes

[1] India’s Open Magazine recently discussed this issue: http://www.openthemagazine.com/article/living/off-my-table-you-damn-carnivore,

[2]For an elaboration of this aspect see this review of the film Aamir by Sohail Hashmi: http://kafila.org/2009/03/19/the-discreet-poison-of-aamir/

[3] The accusation of ‘kabab diplomacy’ is very evident in readers’ comments on this article.

[4] From Mahatma Gandhi’s autobiography: “A doggerel of the Gujarati poet Narmad was in vogue amongst us schoolboys, as follows: Behold the mighty Englishman He rules the Indian small, Because being a meat-eater He is five cubits tall. All this had its due effect on me. I was beaten. It began to grow on me that meat-eating was good, that it would make me strong and daring, and that, if the whole county took to meat-eating, the English could be overcome.” Extract taken from http://www.arvindguptatoys.com/arvindgupta/gandhiexperiments.pdf

[5] Based on information from public sources, though Modi is married, his wife Jashodaben Modi and he have lived separately since their marriage

[6] For more on karmyogis: http://sivanandaonline.org/public_html/?cmd=displaysection§ion_id=1144

Pingback: Secession lagniappe | The Mitrailleuse

Your blog and ts contents are an exciting discovery: many of our ideas appear to converge and I look forward to following you. Regarding “Politics and Modi’s Vegetarianism”, the opposite is true of Pakistan, where being vegetarian would be considered an illness in need of treatment and downright seditious by some! And your sensitivity to any encroachment on India’s hard-won secular democracy is commendable.

LikeLike

شکریہ گل صاحب

shall follow your blog too

LikeLike

Morarji Desai, prime Minister of India between 1977-79, practiced an even stricter form of vegetarianism (he believed in naturopathy, which prescribe thart most vegetarian food be eaten in raw form) than Narendra Modi. No one, to the best of my recollection, accused him of resorting to cultivating an image of Hindu Hriday Samrat. And there have been innumerable news articles about his food fetishes in the politically correct and very secular press.

LikeLike

Of course, we understand that vegetarianism does not automatically imply sympathy with Hindutva. It is however how diet is interpreted that is of more interest to us.

LikeLike

Leave Modi, I’m wondering what kind of food you guys are eating to come up with such convoluted & nonsensical piece of trash?

LikeLike

thank you for your insightful critique. As far as your query is concerned, mostly tamsik. probably that explains the convolutions

LikeLike

Pingback: Opening | Randal Putnam Loves to Pedal

Pingback: Brahminised Environmentalism: Why moral vegetarianism in India is shaky? - Maktoob media