UPDATE (8 September 2014): Lee originally wrote this as a guest post – providing some much needed concrete detail on journal open access policies – but is now with us for good.

Following the launch of HEFCE’s consultation on Open Access for any post-2014 REF, and the generally positive reaction to it here, I examined the potential implications of HEFCE’s proposals for journal publishing in Politics, IR and Political Theory. I wanted to know whether the serious threat in HEFCE’s earlier proposals – notably the rush for ‘gold’ OA and associated Article Processing Charges (APCs) – had been eliminated by a downgrading of the proposals to permit ‘green’ OA, by depositing a ‘final accepted version’ (FAV, i.e. post-peer review, but pre-type setting) into an institutional repository. I also wanted to see what embargoes journals placed on FAVs (i.e. how long after the ‘Version of Record’ (VoR) is published in the journal the FAV can be made public); what re-use was permitted (what sort of licensing); and also to compare this route with the ‘gold’ access favoured by the Finch Report and the RCUK policy. I also wanted to gather information that could be used as part of a ‘soft boycott’ of OA-resistant outlets.

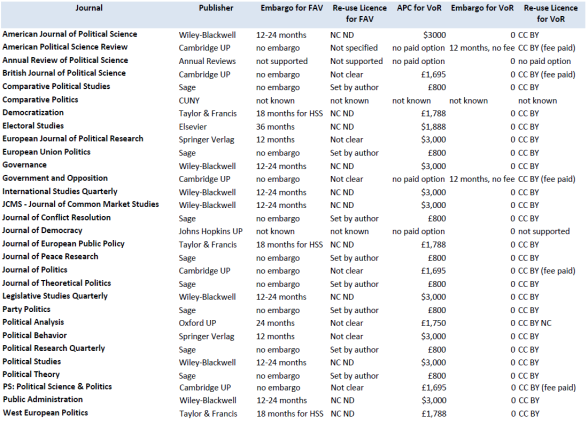

To do this I selected 57 journals that broadly represent the ‘top’ journals in the three subfields. I used composite rankings from Google Scholar, the ISI Citations Index, and surveys of scholars where available, and got feedback on an initial draft. The list isn’t intended to be definitive, just to give us a better sense of where the ‘big journals’ in which many scholars aspire to publish actually stand on OA.

It is not easy to get this information. Policies can vary by journal, not merely by publisher, and their websites are often opaque on the issue of self-archiving, particularly in terms of licensing. This may change if, as seems likely, HEFCE forges ahead on OA; but publishers also need to be pushed to display clearer information. The exaggerated nature of the Finch Report’s estimate of UK HE’s market power to change publishing models is underscored by the fact that US journals tend not to provide the information I was looking for (my thanks to Sarah Molloy for help with this).

The results are presented below for Politics, IR and Political Theory (click to enlarge each image). There are a lot of complexities with various journals which are shown in the full spreadsheet of results which you can see here; the spreadsheet also lets you reorder the information by different criteria.

Several conclusions can be drawn.

(1) Most importantly, Pablo and Meera were basically right: the threat of HEFCE rushing to a ‘pay to say’ approach with hugely detrimental financial consequences for universities and the potential for internal rationing of APCs, has been defeated, for now (although RCUK’s policies remain intact). Some journals, particularly in the US, don’t seem to support green FAV self-archiving, or have gold APC routes – this is a problem because they would be non-compliant with HEFCE’s proposals; so we will need to push for exemptions on this score. However, by and large, where they allow FAV self-archiving, none of the journals appear to charge a fee; HEFCE’s current proposals now intend to compel more researchers to do what they are already entitled to do. So long as this does not change, HEFCE’s proposals should not involve ruinous costs or lead to APC rationing.

However, because the OA issue is fundamentally an ongoing struggle over economic flows, we should be wary of assuming stasis. In the long term, the widespread availability in FAV form of all research conducted in the UK potentially poses a significant threat to publishers’ rent-seeking business models, which rests almost entirely upon their exclusive right to charge for access to research paid for and conducted by others. Although academics currently prefer to have the VoR for referencing purposes, this is hardly true for many other users of research, and may itself change over time. The utility of exorbitant institutional journal subscriptions obviously declines if academics can access the research for free in a different form; cash-strapped institutions may well cut subscriptions. Publishers could try to increase the ‘value-added’ of the service they provide, but a more common response of rent-seekers to external shocks is to reconfigure their practices to defend their unearned rents. To me, this seems the major threat to continue guarding against. (Interestingly, HEFCE has received a Freedom of Information request demanding all submissions made to its earlier ‘call for advice’. Ironically, HEFCE cannot identify the person(s) who made this request for ‘data protection’ reasons, but it is not implausible that it could be a publisher concerned to read the wind and make its own response to the consultation.)

In the case of FAVs, the rent-defending response could involve publishers introducing charges for FAV self-archiving. If this happened after HEFCE locked in OA requirements, universities would be back to where they were under HEFCE’s initial proposals. In responses to the consultation, therefore, HEFCE needs to be warned of this possibility; told that their guidance should insist that no fees are to be paid for green OA; and be prepared to revise/ suspend its regulations if publishers move to exploit them by terminating free FAV archiving.

The ‘green’ route proposed by HEFCE still involves costs, but these will mainly fall at the institutional level in terms of the design, maintenance and staff support for repositories. Universities should be setting aside funds – including seed money received from RCUK – to put the necessarily infrastructure in place. However, to promote the widest and easiest possible access there must not be a rush to develop fragmented, individual repositories. I understand the Russell Group is considering developing a common repository and policies – this sort of scale is necessary and welcome. But why should it be confined to the Russell Group? Wouldn’t it make more sense to create a single national repository, perhaps one managed (and funded) by HEFCE? Imagine being able to use Google Scholar (which indexes repositories) to search for and access – with a single click – every piece of research conducted in the UK! This would largely eliminate the only real value-added of publishers, their large-scale distribution networks (another reason to be wary of their response to all this).

There is thus still a struggle to be had around the governance of green OA. National-scale leadership is required to overcome the fragmented and marketised response to an increasingly incoherent policy thrust.

(2) Embargo periods for FAVs being placed in institutional repositories vary widely. Top marks go to Cambridge, SAGE and Brill, which each impose no embargo at all. Cambridge also allows authors to post the VoR on their personal/ departmental websites as soon as they appear online, and on institutional repositories 12 months after publication – all for free, which is the best offer from any press. Springer-Verlag is next at 12 months, followed by Wiley-Blackwell at 12-24 months, Taylor & Francis and Palgrave at 18 months, and then – unsurprisingly – the profoundly scummy Elsevier at a whopping 36 months. There is therefore still a big fight to be had around embargoes. If Cambridge, SAGE and Brill can all sustain their business models without FAV embargoes, there is no good reason for other presses impose lengthy embargoes, except to extract even fatter profit margins. This is a first lesson for the ‘soft boycott’ campaign.

However, because of the political economy of the publishing sector, using the HEFCE consultation to push for reduced embargoes could have the perverse outcome of reviving the pressure for ‘gold’ OA. Recall that the Finch Report took the unrealistic view that widespread and cheap compliance with very specific OA requirements, like embargo period, could be achieved through the use of UK universities’ market power. The idea was that oligopolistic publishers would somehow be forced to ‘compete’ with each other, driving down embargoes and APCs to acceptable levels. RCUK thus imposed maximum embargoes of 6 months in the natural sciences and 12 months in Humanities and Social Sciences (later increased to 24 months). Compliance with these criteria could be achieved in a ‘green’ manner via FAVs with some journals; for those with longer embargo periods, the researcher would be forced to seek ‘gold’ compliance by paying an APC. RCUK implicitly recognised this by admitting it ‘favoured’ the ‘gold’ route as the fastest way of securing access, and providing (grossly insufficient) block grants to help pay APCs. There is apparently no evidence that this policy – which many research councils have had for a long time prior to RCUK adopting a standardised policy – has driven down APCs or embargoes (see point 4, below). This is hardly surprising given the pathetic leverage that RCUK-funded research has in the global marketplace.

HEFCE’s new proposals don’t suggest any particular embargo; just to ‘provide access in a way that respects agreed embargo periods’. Although it may be tempting to try to use the consultation to push for lower embargoes, the imposition of fixed embargo periods could, rather than successfully pushing journals to reduce embargoes, merely revive ‘gold’ OA. Although a REF-wide policy, covering all UK research, would involve more leverage than just RCUK-funded research, recall that, each year, UK universities’ journal subscriptions total around £100m, whilst Elsevier alone makes $1bn in profits. The UK makes up only 6% of the global journals market. It remains fanciful to believe that we can leverage change just by insisting on certain regulations. It is far more likely that publishers would amend their policies to continue to extract rents, e.g. by lengthening embargo periods, thereby compelling authors to pay APCs to achieve compliance. Again, HEFCE needs alerting to this possibility and safeguards must be established.

(3) The re-use licensing for FAVs also varies considerably, which again raises questions about how publishers would justify their practices. SAGE again comes out well on top for allowing the author to retain their own copyright and decide on licensing. Many other outlets have no clear policy on this. Those that do – notably Wiley-Blackwell, Taylor & Francis and Palgrave – generally only allow NC ND licensing. This means that the work can be distributed freely, but must be attributed, may not be reused commercially, and no derivative works (alteration, transformation or building upon the work) are permitted. For OA purists, this could be seen as a problem, since it is the most restrictive of the six license types promoted by Creative Commons. It definitely avoids the problems identified around commercial plagiarism, reuse, etc, seen by some in the Humanities as a particular problem under RCUK’s demand for CC-BY-ND licensing for green OA (which also deprives researchers/universities of potential IP exploitation rights). However, it is arguably too restrictive. CC-BY-ND, for example, allows work to be translated into other languages, and Braille, but NC ND does not. However, challenging this through the HEFCE consultation could involve similar risks to challenging embargo periods.

(4) The top journals also vary enormously and bewilderingly in terms of OA for VoR. Here the approaches are so complex that there are trade-offs to be made between APCs and embargoes. The standout is probably CUP: as mentioned, it allows authors to upload VoRs to their personal websites as soon as they appear on Cambridge Online, and to institutional repositories 12 months later, with no APC. This unusual position seems to reflect the fact that the owners of journals, not CUP, are the copyright owners. To eliminate the embargo, though, some (though apparently not all) CUP journals offer a ‘gold’ route with an APC of £1,695. Ethics, published by the University of Chicago Press, took a similar approach: the VoR can be made OA in a repository 12 months post-publication, for free; but they have no APC option to hasten this. SAGE is again fairly good, and consistent: authors retain copyright, APCs are relatively modest at £800. Then we are into the familiar realms of the outrageous: Oxford’s APC is £1,750; T&F, £1,788; Brill’s, $2,800; and Wiley-Blackwell’s, $3,000. Several top journals, especially in the US, don’t appear to offer gold OA at all. It remains clear that ‘gold’ OA is generally extremely costly, primarily benefiting the publishers. The costs that would be incurred were HEFCE pushed into indirectly supporting ‘gold’ stream OA remain very high.

In conclusion, I broadly agree with Pablo and Meera that the big threats from HEFCE’s early proposals have been neutered and what is currently proposed is broadly good news for OA advocates. Several issues remain to be contested, but these battles are best fought elsewhere, not within the consultation. However, I’d qualify that by cautioning that the regulatory environment that subsequently emerges could create opportunities for publishers to amend their practices to safeguard their rents. Consequently I suggest that the general tone of responses to HEFCE’s consultation should be positive, but defensive. They need to draw attention to the risks of publishers’ responses and try to suggest ways HEFCE can guard against them. Above all else, if publishers move to impose APCs for FAVs, any insistence on OA could create financial chaos for UK HE and would need to be instantly relaxed. We also shouldn’t forget that RCUK’s policy, with its bias towards gold OA, still exists, and is detrimental.

The priorities now, as I see them, are:

- Warning HEFCE about the potential for rent-seeking publishers to exploit any new OA requirements and suggesting appropriate safeguards.

- Suggesting to HEFCE that its proposed policy be adopted by RCUK, to eliminate their push for APCs insofar as possible.

- Asking HEFCE (and RCUK) to pressure journal publishers to issue clear guidance on OA on their websites.

- In the meantime, continuing to ensure that policies developed for the distribution of APCs within our institutions are needs-based, transparent, defend academic freedom, and do not involve attempts to evaluate the alleged merit of research or authors.

- Pushing for the rapid development of a national, publicly-funded and -managed repository for all UK research to achieve appropriate scale and maximise ease and breadth of access (PLOS is a possible model). Opposing the wasteful development of individual repositories, which drain institutional funds, operate at inefficient scales, are often poorly designed for users, and may make smaller/poorer institutions struggle to achieve compliance.

- Recommending 100% compliance with HEFCE proposals (rather than a lower proportion or exceptions), but conditional upon good behaviour from publishers and the development of a national repository.

- Using our influence with journal editors/ scholarly societies to encourage them to move their journals to ‘better’ publishers, notably SAGE and Cambridge.

- Implementing a ‘soft boycott’ of the worst journals. For the Politics, IR and Political Theory fields, these would appear to be (depending on how you weight embargoes/ APCs):

- Elsevier (based on its 36-month FAV embargo and $1,800 APC, plus its other practices) *

- Oxford (24-month embargo and $1,750 APC) *

- Wiley-Blackwell (12-24 months, $3,000)

- Taylor & Francis (18 months, £1,788)

- Springer-Verlag (12 months, $3,000)

* each of these publishers only have one journal in my sample – their policies may vary substantially across journals. However, Elsevier is well-known to be highly problematic and is already subject to a hard boycott.

Awesome.

Two things strike me. First, it’s interesting that where mainstream, established publishers like Sage are trying out stronger open access policies, they’re doing it through new journal ventures (like SageOpen) rather than by taking the plunge and making an already established brand of journal less pay-walled. This will skew any ‘experiment’ because they won’t be comparing like with like (a high-profile closed journal with a high-profile open journal), instead building in all kinds of hard to distinguish prejudices into the mix.

Second, it’s disappointing that Oxford’s policy seems so poor. They’ve won the contract to publish ISA journals from 2016 and, in the absence of a better open access policy on their part, this means that many of the leading journals in the field will be on the more restrictive end of the spectrum, presumably until at least the early part of the 2020s.

LikeLike

TAKING PUBLISHER POLICY OUT OF THE LOOP FOR HEFCE OA POLICY

Lee makes some good points, but underestimates the power and purpose of some of the very HEFCE policy points that he questions.

It is the fact that HEFCE proposes to mandate the immediate, unembargoed deposit of the FAV in the author’s institutional repository — even if access to the deposit is not made immediately OA — that (1) restores authors’ journal choice, (2) protects authors from having to pay Gold OA fees, (3) takes publishers out of the loop for HEFCE OA Policy, and even (4) equips users to request and authors to provide “Almost-OA” to embargoed deposits, via the institutional repository’s eprint request Button, with one click each.

Institutional repositories start-up costs (a) are mostly already invested, (b) repositories have multiple purposes, with OA only one of them, and they (c) allow archiving costs to be distributed and local, keeping them small, rather than big, like the costs of a national archive like France’s HAL or a global one like Arxiv. Central locus of storage is in any case an obsolete notion in the distributed digital network era.

See:

http://j.mp/HEFCEpolicy

http://j.mp/LOCUSofOA

http://j.mp/oaBUTTON

LikeLike

I very much like the idea of a e-print request button as a way of achieving immediate FAV open access by stealth. I hadn’t thought of that. But not all institutional repositories have this feature. This is a further argument for a national repository, which – as I maintain in another response – has many advantages over a fragmented approach. I find it highly implausible that the cost of running one super-repository will be greater than that of running dozens of mini-repositories.

You also seem to overlook the fact that some journals – admittedly a small minority in the sample – still don’t formally allow FAV self-archiving, as my survey reveals. So your point (2), and thus point (1), are far from certain. Furthermore, as I said, I think it would be naive to assume that publishers will not react, so whether (3) is right remains to be seen. That is why I suggest alerting Hefce to the problems and risks and making compliance flexible when journals don’t allow FAV or APCs, and generally dependent on publishers’ attitudes to APCs not changing. I have been told that CUP people at a recent conference said the only reason they could afford to allow self-archiving of VORs was that so few authors did so. Hefce proposes a vast increase in the number that will do so. Will CUP stand pat? We shall see. For now, I can’t simply support your uncritical cheer leading of these proposals.

Finally, while what you say may be applicable to Hefce’s proposed policy, it isn’t to RCUK’s, which still endorses paid gold access; in this sense I also find your response to the consultation unsatisfactory when you say the former supports the latter. It doesn’t. Ideally the former would replace the latter – that’s something we should be lobbying for in my view.

LikeLike

LET REFLECTION PRECEDE RECOMMENDATION…

I. Both major repository softwares have the Button (and the rest can easily create it, following the model):

http://wiki.eprints.org/w/RequestEprint

https://wiki.duraspace.org/display/DSPACE/RequestCopy

II. Local institutional self-archiving is (a) multi-purpose (not just OA), (b) cheaper than central self-archiving (just local output), (c) distributes the costs (who should pay for the central repository — Arxiv has trouble making ends meet — and why, when it’s not their own research output?), (d) reinforces and converges with funder self-archiving mandates (all research originates from institutions — not all is funded), (e) serves an institution’s other interests (showcasing as well as monitoring their own research output) and (f) makes it only necessary to deposit once, and in the same place, for all researchers (the rest can be accomplished automatically by automatic central harvesting, by discipline, institution, funder, or nation). See: http://j.mp/InstCent

III. You seem to have completely missed the point that immediate-deposit without OA is *not* Green OA self-archiving! Journals have no say whatsoever over institution-internal book-keeping if the deposit is Closed Access rather than Open Access. Indeed the Button is precisely for articles in journals that embargo Green OA, whether for a year or a lifetime.

IV. Your advice to HEFCE to allow exceptions to the immediate-deposit requirement is unfortunately very counterproductive advice, based on a profound misunderstanding, conflating the immediate-deposit requirement with the immediate, unembargoed Green OA self-archiving that Green-friendly publishers endorse and that embargoing publishers embargo. (It is immediate, unembargoed Green OA self-archiving that CUP endorses, and even though I hope my former long-time publisher will never disgrace itself by withdrawing that endorsement, even if they do, all institutions and funders can still mandate immediate-deposit without immediate OA, and all authors can comply.

V. I’m not “cheer-leading” these proposals: I’m helping to design them. If you want to help too, the first thing you need to do is to wean yourself from anecdote and half-truths and get up to speed on the many, many things you don’t know yet about OA and OA policy-making.

VI. HEFCE’s proposed immediate-deposit requirement for eligibility for REF 2020 complements RCUK’s mandate and will help reinforce RCUK’s neglected Green component by providing the all-important Green compliance montoring and enforcement mechanism that the RCUK mandate sorely needs. And the ingenious thing about the HEFCE immediate-deposit requirement is that by its very nature it applies to just about all UK research output (hence just about all RCUK-funded output) because in 2004 a researcher does not yet know which will be his best 4 articles for HEFCE submission in 2020! So the only way to hedge his bets is to deposit all of them immediately… (Think about it!) http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/355015/

LikeLike

I hadn’t heard that – very disappointing and a real missed opportunity. I guess they aimed to maximise revenue, not access to research outcomes.

Perhaps one simple thing we could do is draft a model resolution that OA proponents could aim to have passed at meetings of their professional associations, directing them to shift to OA (or at least OA-friendly) publishers as soon as possible.

LikeLike

I had a twitter discussion with their representative recently, who suggested some scope for looking again at OA policies. Don’t know if anyone properly empowered within the ISA hierarchy might still be in a position to maximise openness on this. I guess someone should make an effort to find out!

LikeLike

Pingback: Open access journal publishing – the change is coming | simonbatterbury.wordpress.com

Excellent. Could do this for other disciplines. But then I thought ( not being in the UK anymore); what exactly is wrong with an individual respository? Mine has been available since 1993 on a stable website and been added to, while working in four different countries and in seven different jobs. Most papers are available there and come up on search engines. An ‘institutional’ repository tied to your current employer would be out of date (when you leave and move on) and time consuming (uploading publications repeatedly to different institutions, or crosslinking back to your last ones-which some universities would not like). Imagine loading up an increasing number of publications to an IR at seven different universities.

What is wrong with unis encouraging people to maintain their own, and asking you, on new employment, to verify that you have one (on wordpress or whatever) or to contribute to theirs to meet the national requirements? I ask this because the chances of holding and retaining a single job in the UK are now poor, and the workforce has internationalised so much, with many moving round the world like I have done.

As an extra – I need to add a licence (CC-BY-ND or whatever that means) to my journal (http://jpe.library.arizona.edu) which just has words about authors retaining copyright at present. Any suggestions? Too many choices for the un-initiated. Thanks

LikeLike

There is nothing ‘wrong’ with such a strategy, and I don’t think anything in Lee’s post suggests there would be. Indeed, this is the general green route which will likely become dominant. The point is that different journals have different repository policies. These policies apply to the ‘FAV’ versions (post-peer review), not just to the final copy-edited ‘VoR’ (versions of record). So it will make a difference whether you go for Cambridge (immediate VoR ‘personal’ repository) or Wiley-Blackwell (up to 24 months for FAV institutional repository). Pressures can usefully be applied to bring those periods down, as well as to ensure that publishers don’t feel that it is possible to go APC-only (which they technically can whilst still being compliant with UK policy).

LikeLike

Thanks Simon. The reason I advocate a national repository is threefold: to maximise user ease and access, to minimise costs, and to maximise compliance. A national repository is best for users of research because it is a one-stop shop for all research outcomes. They know where to go, and they can become familiar with one website and one way of accessing items, etc. Think how many lame institutional repositories there are out there right now, with countless clicks to get through, only to find no file at the end, or a demand for an institutional login. Well designed, a national repository would do away with all that and even allow people one-click access from google scholar. A national repository is also less costly and more efficient. Rather than tens of thousands of individual academics maintaining their own repositories – which many are not tech-savvy enough to do – or dozens of institutions (or smaller numbers of institutional / mission groups) making their own, duplicating procedures, inventing clashing access procedures, etc, it makes obvious sense to pool resources and design a functioning, well run, well designed repository for all to use. This also takes the cost burden off individual universities and shunts it back to the institutions actually pushing for OA, like Hefce and RCUK. It’s about time that regulatory costs were assumed by those who impose them. It also makes it easy when people move jobs, because they don’t have to start over. Lastly, a national repository makes it easy to monitor and therefore enforce compliance, while minimising costs. Ensuring that all work submitted for the REF is in a repository is easy if Hefce can simply issue a standard spreadsheet to HEIs, then run it through their system to check it against their own repository. It becomes incredibly cumbersome if the work is spread across dozens, hundreds or even thousands of fragmented repositories. Compliance either cannot be enforced, or the costs of ensuring compliance will, as with repository costs, be shunted down to HEIs, with yet more useless bean counters hired to check off each item submitted.

LikeLike

What if you move country?

LikeLike

So, I moved to the UK in 2017. And ORCIDs have come in, which addressed my point about portability of a single scholar’s record around the world, at least. Since 2013, it looks as though ‘institutional repositories’ are still mandated quite widely, but Researchgate and Academia.edu, both portable of course (if potentially unstable, since commercial and liable to incur costs, be bought out, or disappear one day) have been the archives of choice. My former employer actually searches them and adds links in its own institutional archive.

LikeLike

Pingback: HEFCE/REF menyatakan sokongan & mandat terhadap initiatif Open Access | MALAYSIAN OPEN ACCESS SUPPORT GROUP

ozens of institutions (or smaller numbers of institutional / mission groups) making their own, duplicating procedures, inventing clashing access procedures, etc, it makes obvious sense to pool resources and design a functioning, well run, well designed repository for all to use. This also takes the cost burden off individual universities and shunts it back to the institutions actually pushing for OA, like Hefce and RCUK. It’s about time that regulatory costs were assumed by those who impose them. It also makes it easy when people move jobs

LikeLike

So the information on Sherpa-Romeo is wrong? For Electoral Studies it says:

“Voluntary deposit by author of pre-print allowed on Institutions open scholarly website and pre-print servers, without embargo, where there is not a policy or mandate”

I thought all Elsevier journals had the same policy.

LikeLike