At the heart of recent discussions on work lies an enduring tension. We can sense that modern work isn’t working anymore, but we don’t know how to let go of it. The disintegration and degradation of wage labor through technological “progress,” increasing commodification and devaluation of reproductive work, steadily rising unemployment and precarious employment, and sustained attacks on the last bastion of permanent employment (the public sector) together with our desperate attempts to resurrect a corporatist corpse that won’t return, all point to the fact that modern employment “exists less and less to provide a living, let alone a life.” Marxist outliers (Andre Gorz, Ivan Illich, Antonio Negri, Zerowork) have been announcing a crisis of work for some time now, remarking how automation both reduces necessary labor time and degrades work without, however, releasing us from the obligation to earn money for a living. Today work persists in a zombie state despite the disintegration of working class culture and organizations and a continuous process of proletarianization. These conversations have returned in full force in recent years with the publication of Kathi Weeks’ groundbreaking The Problem with Work: Marxism, Feminism, Antiwork Politics and Postwork Imaginaries and a sustained interest in these matters in the Jacobin and even mainstream media.

In these debates, however, there remains an unreconciled tension between the obligation (of any self-respecting socialist) to celebrate work as a source of collective power and personal pride and the more futuristic desire to overcome work and even our self-understanding as workers for a more multivalent understanding of life. This is effectively the tension between Marx and his son-in-law Lafargue, between laborists and anarchists, between a politics of equality and one of autonomy. Of course, there can never be a satisfying answer to this problem because the dichotomy itself is a sectarian caricature. Much more interesting would be to stick with this tension as a provocation for a politics whose form and direction has yet to be decided.

How do we, at once, celebrate the types of cooperation, organization, and identities born out of wage labor and recognize that these are inadequate and insufficient modern inventions that have run their course? How can we advance the cause of wage laborers and fight for people to one day stop functioning as workers? An impossible (and scandalous) proposition such as this is the “refusal of work,” the Italian autonomist theory/practice, which claims that workers are able to produce and sustain value independent of capitalist relations of production and centralized power.

Italy during the 1970s was a laboratory for new types of political activism and thinking. The wave of revolt began, like in many other places, in the late 60s with workers demanding wage increases, shorter work hours, and greater workplace democracy. Very quickly, though, the movement extended from factories and formal channels of political mediation into the streets of metropolitan centers, where it swept up students, precarious workers, and women, and acquired a much more autonomous character. By the mid-70s, a newly formed “social stratum recalcitrant before the notions of salaried work” started experimenting with ways to stage a collective exodus from capitalist life (not unlike Occupy). Bus riders refused to buy tickets, young people stormed theaters and cinemas for free, city dwellers stopped paying their rents en mass, students occupied universities and squats, and women demanded wages for housework. Autonomists did not limit themselves to a standard critique of exploitation in work. Neither were they purely troubled by alienation. Their ambition was the “refusal of work,” to reject work as “the highest calling and moral duty,” the ultimate measure for value, recognition and status. A heresy like this could only end in “failure.” By the end of the 70s, the movement found itself squeezed between state repression, from the one side, and armed terrorist struggle, from the other, unable to propose a viable political program for workers but against work.

This tension between the anti-work and the dignity-in-work position or between students and workers is dramatized excellently in Elio Petri’s little-known gem The Working Class Goes to Heaven (1971). Already in the second scene, which shows Italian students trying to organize workers at the factory gates, we begin to distrust such an alliance.

Workers! Workers!

Do it for your student comrades

It is 8 in the morning! When you come out it will already be dark

Today for you the sunlight will not shine

You will be doing piecework… 8 hours of piecework

And you will come out old and empty

Convinced you have earned yourselves a day-wage

And instead, you have been robbed! Yes, Robbed!

Workers, you are entering prison!

The film reaches its climax when one of the workers, suggestively named “Lulu the Tool,” loses his job, family and mind after taking the “refusal of work” to heart, and turns to the students for help only to receive empty Marxist slogans instead of genuine solidarity. Petri’s film confirms what we suspected about the New Left all along: a politics of refusal that lacks a social basis for struggle or any relation to material conditions cannot effect lasting social change, and will dissolve into childish extremism. Although a fair point, thus is also a much too convenient way to discredit utopian demands for less work and more pay (work reduction, wages for housework, basic income), and turn them into a “realistic” program for creating more and better jobs.

Today, the “refusal of work” lives on more as a path than a concrete goal. It is used more to restore confidence in the “invention powers” of workers than as an actual strategy for mass revolutionary struggle. The basic Autonomist insight is that labor is an inalienable property of human existence which capital systematically tries to bring under its control and channel towards profitable ends. However, this process is never complete or ultimately successful. Since labor power is the source of all wealth creation, workers always have the ability to produce and create value outside capitalist imperatives. What this might look like, however, has been left intentionally vague to defang the “refusal of work” of its anti-workerist connotations. Kathi Weeks’ book, for instance, manages to get away with having both the terms “antiwork politics” and “postwork imaginaries” in the title of her book only by letting these function as performative utopias, used to provoke desire and movement, not concrete alternatives to the present. By demoting the “refusal of work” from practice to provocation, its offensive and dangerous qualities are tamed and its detractors largely appeased. This way, the “refusal of work” is never at risk of becoming an actual “refusal to work.”

Doing nothing is a heresy of athletic and self-destructive proportions, frightening to both liberals and socialists, which is why it has usually been left up to artists, anarchists and punks. Bartleby’s “I would prefer not to” is the consummate refusal. What starts out as a refusal to do his job slowly becomes a refusal to perform the work of reproducing his body, his slow-motion suicide showing just how coterminous work and life are. To refuse work is ultimately to refuse representation, even the representation of one’s body.

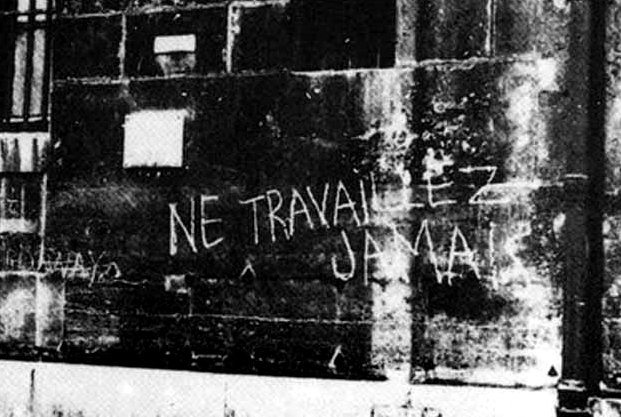

In the 60s, the refusal became a common tactic of revolt. Situationists insisted “Never Work!” and existential Marxists claimed that since all life is already subsumed to capitalism, doing nothing is the only virtuous option. In the film Un homme qui dort (1974), Georges Perec tells the story of a young man who decides to leave this world without actually killing himself. “You eat, you sleep, you walk, you are clothed. Let these be actions or gestures, but not proofs, not some kind of symbolic currency. Your dress, your food, your reading matter will not speak in your stead. Never again will you entrust them the mortal burden of representing you. You put on your shirt and coat, you read the paper, you pay your electric bill, you ingest, once or twice a day, rarely more, a calculable compound of proteins and glucosides…” and so on. Perec’s hero does just enough to remain alive, which means that, different from Bartleby, his refusal has no foreseeable end in sight. To not work is to exist outside of time.

A non-productive attitude is not an uncommon thing in art. Being the single other artifact, aside from money, whose value is entirely a construct of our imagination, art is always under pressure to convince us of its worth through constant production, representation and claims of authorship. Artists have tried to resist this injunction to perform, for instance by living the social life of an artist without making any art. If capital is accumulated wealth, the bohemian attitude has been to squander anything of value. If the bourgeois urge is to save and stash away, the artist wastes and gets wasted. This is not even about resistance, since resistance is also an instrumental activity that hopes to produce an event or model of opposition. It is non-action that exists outside the dialectics of cooptation and resistance. Yet to be uncooperative is not just to refuse to produce the content of communicative capitalism. It also means to refuse to communicate oneself and build communities with others. This is the problem with complete acts of refusal. For the “No” to be seen, there must also be a “Yes” to representation, communication and action. In the long run, a practice that refuses the latter is a kind of creative death. Even Bartleby needed Melville to do the work of representation for him.

When looking at the actual history of refusing work, we don’t see the welfare scrounger or the self-contented idler. What we see is nihilistic exhaustion, gratuitous expenditure of energies, a systematic suppression of all that is useful and productive in us to maintain an artificial and ultimately anti-humanistic stance of deliberate inactivity. Refusing to work is an act of sacrifice, a performance for others at the expense of oneself. Watching others not work helps us realize both how deeply lodged the Protestant values of personal responsibility and productivity are inside of us and how delusional it is to think that we could ever escape the material obligations of life. Exercises such as these cannot but be short-lived and disastrous. Constantly oscillating between exhaustion and exuberance, they are meant for failure from the very beginning, their failure only reinforcing that there is no path worth taking.

The difference between the Autonomist “refusal of work” and this much more drastic “refusal to work” is not that one is affirmative and the other nihilistic. (There is, in fact, a great will to power in these exercises of social resignation, they just happen to look like art, not politics.) The difference is that one presupposes a collective act of self-creation, whereas the other is an individual feat of endurance. Whereas one is trying to pool together our tools and resources for survival to stage a collective exit from wage labor, or at least a relaxation of its grip, the non-productive attitude refuses to engage with questions relating to the reproduction of human life. Who picks up the pieces when you reject work? Who does the work of recognizing your spectacular acts of inactivity? And who helps you when you fail? A feminist politics of refusal or a refusal “from below” would look very differently. Instead of remaining trapped between two ideal positions of submission and inaction, it would recognize that all forms of action and inaction are already indebted and dedicated to someone else’s labor. To act, therefore, is also to care or to be grateful.

Jan Verwoert: To All Those who Set the Stage from Smart Museum of Art on Vimeo.

To take a most explicit example, in the acclaimed anarcha-feminist sci-fi novel, Woman on the Edge of Time (1976), Marge Piercy imagines an egalitarian, communistic society where all work is mechanized except for child rearing and agricultural work. The very activities we tend to think of as most cumbersome and tedious are, in fact, the most essential to life and to collective self-determination. The realm of necessity becomes the realm of autonomy.

Autonomist feminists and ecofeminists flatly reject the great modernist promise that technological progress and planning will deliver us from material obligations into a world of cognitive work and creativity. Not only has automation not created the conditions for an egalitarian society, but the fantasy that freedom lies outside the realm of necessity is also a most bizarre form of fetishism. No amount of automation can replace the work of physically and emotionally reproducing life. Neither should this work be mechanized. If dead labor separates people from themselves and the world around them, through labor for life “persons come to belong to themselves and to one another in their communities” and become “rooted in their sensory materiality of the world and to share that world with others.”

To resist the hegemony of wage labor while maintaining the social usefulness and creative satisfaction of work requires access to collective, autonomous forms of subsistence. That is why the struggles against modern enclosures waged by indigenous people, landless peasants and women in the Global South are, in a sense, struggles against work. If we consider that modern work has its origins in the violent expropriation and separation from common means of subsistence (land, resources, tools, skills, knowledge, culture, social bonds), displacing the centrality of wage labor (and the commodification of life) can only begin with reclaiming the commons and restoring the centrality and dignity of reproductive labor. According to the prefigurative utopia described in Woman on the Edge of Time, the result could be a world where there no longer is a difference between caring and creating, and maybe even art could stop functioning as art.

Interesting piece. I was recently talking to a few feminist political economists about the hostility they often receive from conservative/marxist political economists about how socially reproductive labor isn’t really ‘labour’ and that non-valorized work isn’t a necessary metric.

I just wonder to what extent parenting/education/caring functions as work in the matrix you outline above? The fights for access to social programs (childcare and education funding) to help caregivers, is in a way about the right to ‘work’, because they should also have choices about how they engage their laboring practices. You mention Federici in your tags, I just wonder where social reproduction fits in here?

LikeLike

Excellent article. I tweeted it and expect my followers to retweet it.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on horstbellmer and commented:

Work and the Politics of Refusal

LikeLike

I think each person has to define what they mean by work/play. It is really different for different people. Being with children is play for me in a context where meals, cleaning etc are taken care of. As in a free school. Unless meal prep is a part of what you do together.

LikeLike

Pingback: Work and the Politics of Refusal | ΕΝΙΑΙΟ ΜΕΤΩΠΟ ΠΑΙΔΕΙΑΣ

Pingback: Victory At Last | QU South Africa