-“I Ain’t Got No Home in this World” by Woodie GuthrieI ain’t got no home. I’m just a roamin’ round, just a wandering worker, I go from town to town. And the police make it hard wherever I may go. And I ain’t got no home in this world anymore.

My brothers and my sisters they’re stranded on this road. A hot and dusty road that a million feet have trod. Rich man took my home and drove me from my door. And I ain’t got no home in this world anymore.

Was a farmin’ on the shares and always I was poor. My crops I lay into the banker’s store. My wife took down and died upon the cabin floor. And I ain’t got no home in this world anymore.

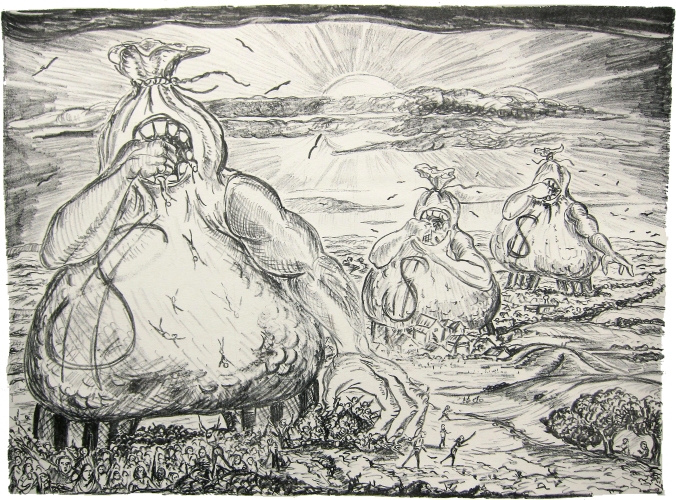

Now as I look around it’s mighty plain to see this world is such a great and funny place to be. Ah, the gamblin’ man is rich and the working man is poor. And I ain’t got no home in this world anymore.

Beginnings Are Difficult

How to start something new? This question troubles the academic as well as the activist. At the moment it troubles me both as a question of inquiry and as a meta-question of method.

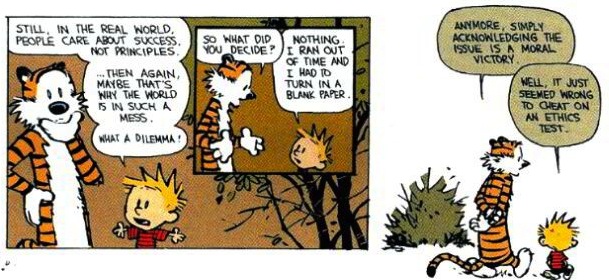

In my previous work I have argued that human rights should be judged first and foremost by the consequences they bring about. Do human rights enable new forms of politics? Do they enable politics that increase the control we have over our lives, or that reduce the suffering and humiliation we are exposed to? Or do they confine us in a liberal subjectivity that makes wider visions of justice impossible, which push us to reconcile our beautiful revolutionary dreams to the limited horizon that contemporary liberal capitalism imposes?

I have offered a qualified defense of human rights as a democratising ethos, which suggests that human rights can enable everyday people to challenge the terms of legitimate political authority, including the institutional shape of their government and the makeup of their communities. This is done by formally opening up the identity of “rights holder” to anyone, regardless of their social position. This opening, however, is only formal and in that formality human rights have an ambiguous significance. For this reason, I have argued that to think of human rights as a democratising ethos also requires that we attend to the politics of human rights. This means that ensuring that human rights support democracy and equality is a political struggle as well as an ethical vision.

This understanding of human rights is speculative and depends upon an examination of the consequences of human rights. It requires an answer to the question: Do human rights actually serve the end of radical democratic change? I have just begun a project that attempts to answer this question by looking at social movements that have used the language of human rights to claim a right to housing. Taking my work in this new direction generates two worries, two uncertainties about what it means to begin.

First, this new line of inquiry is explicitly about the capacity that human rights have to open political space, to give birth to the new – in this case to new rights to land and housing. Can human rights serve movements that seek to reconstruct property rights in a fundamental way? To answer this question I am looking at a number of political movements in which human rights have been used to redefine the basic terms of the political and economic order. My plan is to study and engage with the Landless Workers Movement in Brazil, which has claimed a human right to land based on the productive use that everyday people make of “property” that is owned but either unused or used for socially destructive ends; the West Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign in Cape Town, South Africa, which has sought to organise poor communities facing eviction and various forms of deprivation to enact their right to housing through direct action; and the diverse groups working in the United States under the banner of ‘Housing as a Human Right’, whose work I detail below. My hope is that learning from the communities and individuals engaged in radical and transformative politics will lead to insights into the possibilities opened up, or closed down, by human rights ideals and institutions.

Second, beginning this project raises a series of difficult questions about how ethical inquiry should be done. Implicit in what’s been said thus far is a claim that ethical inquiry needs to engage with the world, it must seek to know something about how the good is sought, defended, opposed, rejected and thwarted in the lives of everyday people. Making this claim at all, much less making it explicit, raises issues that are best (though imperfectly) described as methodological (both in terms of methodology and methods) and which usually go unaddressed by those working on ethics as an academic discipline, whether theoretical or applied. Following the logic of my own process of reflection and inquiry I will start with this second question of beginning and then move to the first question – using initial research I did in the USA during March and April 2012.

Ethics and Critical Social Inquiry

The study of ethics is dominated by rationalist forms of inquiry that are largely hostile to the idea that ethics have an importantly empirical aspect. Whether we begin from the transcendentalism of deontology or the instrumentalism of consequentialism, the world of everyday experience hardly needs to be considered. It is telling that the distinction between facts and values remains as contested as ever, and the risk of running afoul of the naturalistic fallacy is still live. Even where intuitionists have made forays into the field of “experimental ethics”, these “experiments” are designed to confirm the accuracy of the philosopher’s presumptions about “our” intuitions, rather than examining the deeper role of intuition in ethical reasoning.

There are strains of ethical thinking that emphasise practical reason embedded within social traditions, but these contextualist understandings of ethics tend to constrain reason without suggesting the good or the right are objects of inquiry that we search for in the world of everyday experience, in all its multiplicity and ambiguity. And those who dare to tread such a path are quickly accused of relativism, an abandonment of the idea of moral truth. Moreover, even those thinkers that risk the charge of relativism, who suggest our values are ironic commitments or singular moments of choice, rarely study the whole of ethics.

Why is that we so rarely consider the logic of ethics (encompassing the formal properties of ideas such as the good, or the function of ideals and standards in human conduct) in tandem with its psychological dimensions (such as the habitual aspect of ethical conduct and when/why moments of ethical decision are brought to our consciousness) and the place of ethical ideas in our social institutions and customs? If we think that ethics is a matter of rational reflection, in whatever mode, such an empirical or naturalistic ethics is secondary at best, and unnecessary at worst. Determining what is right or what justice demands can be done with minimal engagement in the world, even if knowing something of the world is important for applying the philosopher’s wisdom – hence the proliferation of “applied ethics” manuals. And if we think that ethics is irrational, is a matter of commitment or poetic creativity, then the appropriate test of such an ethics is authenticity rather than consequence, is individualised rather than socialised.

I do not want to suggest that the world, either scholarly or lay, is filled with radical rationalist and irresponsible relativists. The distinctions I am drawing here highlight tendencies and tensions that pull us as we contemplate ethical questions in a systematic and thoughtful way. In response to these stultifying tensions I have suggested a situationist ethics based in the work of John Dewey, which sees ethics as both an inherited set of customs and institutions, as well as an active engagement with the world. We are inevitably already in the world, a world dense with values, goods, duties, obligations and privileges that define our many relationships with each other. To study ethics, then, is to understand how these ideas function conceptually, how our psychology leads us to conform and dissent from the given ethics we find, and how they are embodied in society. Yet, custom and tradition are insufficient justifications for ethics, for the job we expect them to do – constraining our behaviour and improving our future actions. The critical dimension of ethics is pursued when we face moments of crisis and indecision, when we must question the goods we are given, making choices, commitments, compromises and, sometimes, making new values. Reflection is insufficient, however, as a situationist ethics insists that the solutions we find to our ethical problems must be put to the test of the world. In the always ongoing work of being ethical, we may find that our ends are no longer worthy of our effort, or we may find that our dearest values require great effort to change the world of our experiences, or we may find that we need new ends. This work is always partial, contestable and ongoing.

Taking this starting point, ethics becomes a form of critical social inquiry and can no longer be divided off from empirical studies not only of what “we” take to be the good of individual and social life, but also of the consequences of pursuing and realising our ends. This critical social inquiry is, however, an inquiry in context – situationism demands a different kind of investigation, drawing on the tools of the social scientific tradition, but not reducible to any conventional practice of social science. The end is not to find truth or produce knowledge, but to inform and improve our conduct through intelligence – though doing so will involve new knowings.

Housing is a Human Right, USA

Well armed with my convictions, however, I find myself entering a strange intellectual territory – seeking to study both what human rights are as ethical claims and their consequences in specific social contexts, in spaces where human rights ethics is being practiced. Yet this is only half the job, as what remains to be done is to offer an evaluation of how far human rights enable the ends they are intended to serve, as well as the value of those ends. How one does this is not only unclear but fraught – to conduct such an inquiry is to become involved in ethical and political work, to do and to participate, to claim some authority and to take responsibility. This is a very different orientation in ethics, rejecting the authority of theory and giving the everyday practice of ethics pride of place.

I came to study the movement for a human right to housing/land in part for academic reasons – the use of a human rights framing to make radical claims that undermine core presumptions of liberal ideology is important to my broader thinking. Yet that is a partial motivation. I was drawn to this study because I am moved by deprivation and inequality. I cannot stand to see women and men of good character and dignity made to feel powerless, small and abused. I am convinced that patterns of land distribution and property ownership contribute to social misery in ways that can be countered but for want of an alternative to capitalist social relations. I am convinced that if human rights do not help us to address these issues – in our varied but connected global context – then their worth as a political ethics is doubtful.

Despite these convictions I initially hesitated to “study” the movements of committed women and men fighting daily to improve their own lives and those of others – it seemed intrusive and my contribution to that work unclear. For that reason I chose to begin in the US – in the country of my birth – because I had a dog in the fight. Growing up working-poor I knew what it was to worry month to month if you could pay rent, saw relatives and friends lose their homes, and I felt a compulsion to contribute in some way. The process of doing that is only started but has proved a rewarding challenge.

I can only offer an unfinished vignette here, so to Chicago…

I had talked to Loren Taylor on the phone from London two weeks before I met him in Chicago. When I first spoke with him on the phone he was taking part in an eviction defence for Patricia Hill, a resident in the south Chicago neighbourhood of Bronzeville. Along with volunteers and other members of the Chicago Anti-Eviction Campaign (CAEC), Loren was occupying Ms Hill’s home to prevent her bank (Bank of New York Mellon) from evicting her. When we met finally, he offered to show me around Chicago and give me some background on how the fight for a human right to housing had taken shape in the city.

In Chicago, the movement for a human right to housing is a fight on multiple fronts to protect poor and working people from eviction and fraud, and to ensure affordable housing for the city’s residents. Cabrini Green was an infamous Chicago housing-project and it provides a snapshot of what a human right to housing means in the city. The housing project was a long standing target for demolition, as it not only sat on valuable real-estate on Chicago’s near north-side, it was a community beset with crime and chronic poverty. Nonetheless, Cabrini was a community and efforts to tear it down were opposed by residents who feared they would not only lose their homes but that they would be displaced to the fringes of the city.

The first struggle that Cabrini residents faced was to claim social housing as a right, emblematic of a social relationship between society and its least advantaged residents. The city of Chicago (and the US nationally) did not acknowledge or uphold such a right. Instead the city sought new ways to clear the housing-project, which included evicting anyone accused (not convicted) of a crime. As if this was not draconian enough, the policy applied to entire households and the accused need not have been a permanent member of the household. A houseguest accused of a crime was enough to justify an eviction. When this failed to clear the housing project quickly enough, the city resorted to entrapping residents who had to walk through a condemned part of the housing-project to get to the local neighbourhood – an act of trespass, which the police used as an excuse to charge residents as they went about their daily business. In time, Cabrini was torn down and sold off to developers and land speculators. Walking through the neighbourhood today, there are numerous empty lots and vacant buildings, as the financial crisis that started in 2008 prevented the development that justified the disruption of so many lives.

Cabrini residents ousted from their homes then faced the problems poor residents throughout the city faced – a lack of affordable housing, predatory lending by mortgage companies targeting communities of colour, gentrification and land speculation that drives up rents and a city government allied with lenders to such a degree that fraudulent practices were tolerated. To address these issues the political struggle necessary and the types of ethical claims being made needed to change – no longer was it about simply protecting public housing but ensuring that each individual has a right to a secure home.

And the economic crisis and lingering recession has brought this inhumane condition into high-relief. Chicago is a city with a growing homeless population, a mass of individuals and families struggling to find safe and affordable housing, an exodus of communities of colour and working poor from the city (some estimates suggest that Chicago has lost 100,000 residents in the last 10 years), neighbourhoods increasingly dotted with vacant properties and numerous households facing foreclosure.

As Loren describes it, the key thing that fighting for a human right to housing does is that it changes people’s perspective, they go from being an isolated individual beset by personal failing, ridden with shame and guilt, to understanding that not only are the conditions of their life social in nature but that for everyday people the current relations that define home ownership and housing rights are not working. Along with changing the self-understanding of those facing eviction, foreclosure, homelessness and a lack of safe and affordable housing, fighting for a human right to housing on the CAEC’s model involves the organisation of effected communities to fight back, not only through legal means, but through direct actions, which include eviction defences (such as the one I visited at Ms Hill’s home) and the occupation of vacant homes (what CAEC member JR Fleming describes as connecting homeless people and peopless homes).

These tactics violate the law and challenge the basic terms of legitimate social relations. And, as the CAEC’s long-term interest in community land trusts shows, they have an alternative model of economic and social relations in mind, which involves not only the social guarantee of housing but also a reconfiguration of property rights as such. CAEC’s activity, both strategically and ethically, is framed around the idea of human rights, but an understanding of human rights that is deeply political and starts from the idea that a right is a demand enacted and secured by the people most affected by onerous social conditions.

A fuller account and analysis of my fieldwork will have to wait for a later post, but what I have taken away thus far is that engaging with the practice of human rights is vital to how we understand them, both as intellectuals and citizens. I was struck by a comment JR Fleming made to me. He told me how he and other activists opposing the demolition of Cabrini were hopeful when the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing (Mrs Raquel Rolnik) wrote a critical report after her visit to the US. His naive expectation that the UN would do something about what was happening in Chicago was quickly dashed, but his energy, thankfully, was redirected. JR told me about meeting with activists from South Africa, who joshed him out of thinking that the human rights of everyday people in Chicago would be protected by national or international law and roused him to direct action.

Human rights are not a thing out there in the world for us to discover and observe, they are rather something that we do, which means the different ways they are done are important. Beyond confirming and informing an understanding of human rights that I have been thinking about for several years now, my time in Chicago also left me with a pressing question: what is my role as an outside intellectual? I cannot pretend to have much of anything to teach Patricia Hill, Loren or JR – I am learning from them, from their actions and their willingness to include me, even briefly.

As I work through my field notes and reflections, excited for the project ahead, it’s this question that lingers – how does critical ethical inquiry go to work? For now, it’s through conversations, through connecting the people I’ve meet to the people I know, through blogging and papers, and hopefully in the following year additional trips to work with the groups I met for a longer period of time contributing, at the least, my hours and energy to their endeavours.

Just fantastic Joe!!! Kant replaced the priesthood with the academic. you are saying goodbye to Kant. Once we say goodbye to Kant we then have to retrieve another meaning to aesthetics, wherein sensibility is integral to ethics and knowledge production. It is not the long convoluted propositions packed with terms of art that reveals. being with people who know a struggle is its own university. let us exorcise the university of kant and build critical solidarities with our many universities.

LikeLike

Enjoyed what I read Joe, my son, :), I never knew about what happened with the Cabrini Towers in Chicago – I remember when I got out of HS – yep in the dark ages of 1970 – I used to drive by close to that area to go to work. I’m not surprised it’s gone and mostly empty now as developers couldn’t continue –

LikeLike

really interesting piece. Apart from approaching the issue with loads of vigour and enthusiasm, it’s great to gain insight into the mind of academics/intellectuals who are careful to question their own role, purpose and utility. Particularly when studying social movements such as these. I learned a lot from this, thanks.

LikeLike

Pero todo este trabajo se marcha al garete si te metes en la ducha y te olvidas de cerrar el

grifo durante 10 ó quince minutos.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on radicalsubjectivityblog.

LikeLike