With the biggest economic crisis since the Great Depression continuing to slowly unfold, one of the most surprising consequences has been a non-event: the dearth of high-quality economic theorizing in leftist groups. [1] This is in spite of the opportunity the crisis presents for alternative economies, and in spite of the economic conundrum that developed economies find themselves in: too indebted for stimulus and too weak for austerity. This differend between austerity and stimulus indexes the insufficiency of either and yet few have taken up the necessity of thinking proper alternatives.

The leftist response to the economic crisis has instead been mostly been to focus on piecemeal reactions against government policies. The student movement arose as a response to tuition fee and EMA changes; the right to protest movement arose as a response to heavy-handed police treatment; and leftist parties have suggested a mere moderation of existing government policies. The project to bring about a fully different economic system has been shirked in favour of smaller-scale protests. There is widespread critique, but little construction.

Admittedly, the left is not entirely devoid of high-level economic theorizing. Rather, the more specific problem is that those few who do such work are a relatively tiny minority and are typically marginalized within the leftist scene. The attention and effort of the leading intellects of leftism (at least in the UK) are on social issues, race issues, rights issues, and identity issues. All important, to be sure, but there is no equivalent attention paid to economic issues.

The current academic literature on leftist economics is little better. In the words of Alex Andrews, this body of work can be roughly separated into three general tendencies:

1. Marxists – tend to operate in a critical mode. They provide the best analysis of the conditions of capitalism of the other groups. But in terms of talking about the economics and organisation of a post-capitalist society, the analysis is rather thin. This is part because economics was historically associated with a vulgar economism (which Marxism is not ultimately) that was linked to Stalinism. And it is part, of course, partially to do with the idea that the democracy of the workers movement would generate this construct.

2. Critical Realists, “Post-Autistic” school people, Tony Lawson, Cambridge Social Ontology group – strong critique of neoclassical economics, but lets be honest, this is shooting fish in a barrel. No positive project. Unlike mainstream economics that never talks about methodology, they *only* talk about methodology.

3. Keynesians – no class analysis, no wider politics, no understanding of why Keynesianism may have failed politically, or how it is the flip side of current situations.

As Alex notes, none of these approaches is sufficient on their own. Yet even more worryingly, I’ve been present at a number of events where it’s argued that leftists needn’t worry about such issues right now. Instead it’s suggested that all we need is to bring about a revolution (as though revolutions were some clean cut with the past, rather than being a complex mixture of diverse social forces). The presumption implicit in this response is that once leftists are given the opportunity to create a new society, the answers will just become clear. Perhaps through consensus decision making we’ll come up with a sophisticated answer…!

But the risk of relying on such unreflective people power is that when the opportunity comes to effectuate change, the actors involved fall back on habitual ideas simply because they can’t imagine an alternative. This is a crisis of imagination, but also – more significantly – of cognitive limits. Very few have done the hard work to think through an alternative economic system. And as a result, we remain embedded within capitalist realism – unable to think outside the socio-economic coordinates established by an all-encompassing capitalist imagination. Slavoj Zizek has been a popular exception here by consistently arguing for the necessity of thinking “the day after tomorrow”. Yet few appear to have taken up his call, and he himself seems to have ignored it as well.

This all raises the question of why this is the case. Here it seems to me there are three primary reasons for this neglect of economics in contemporary leftist circles.

In the first place there is the continued adherence to a form of ‘folk politics’ – the avoidance of systemic and abstract thinking in favour of immediate and bodily forms of action. Getting struck by a cop at a protest becomes a sign of success, at the same time that it displaces the conflict from incorporeal structures to physical individuals. Yet the systems that determine economic outcomes are complex and abstract, making them alien to everyday experience. We experience their outcomes, but only at a deferred distance (see my last post for more on this). It’s much more intuitive for individuals to protest and occupy spaces than it is to trace out causal chains and uncover more abstract spaces of contention (e.g. bank capital reserve requirements). Yet the latter are exponentially more effective in the long-run, albeit much less exciting. (This has led some to posit a protest trilemma between being effective, being risk-free and being exciting.)

Another part of the explanation for the missing economics has to point towards the cultural turn of the 1980s in the theory and activist scenes. Rather than continue to read Sraffa, Hilferding, Baran and Sweezy, a generation of students grew up focusing more on the issues of identity politics and the post-structuralist critique of subjectivity and desire. This is not to begrudge cultural theory for its achievements, but simply to point out that this became the dominant pathway for most students during this time. Those with a broadly leftist sensibility were immersed in this milieu, and opportunity costs dictated this was at the expense of economics training.

Yet this leads to the third, and more important, explanation. Because while most leftist students may have been raised in an era of cultural theory, one would still expect the current crisis to have brought about a major turn in leftist circles. One would expect a massive influx of leftists suddenly interested in economics and the scholarly work it requires. Yet, for the most part, this shift remains unseen. It seems to me that, as a result of the training of students in cultural theory, many leftists consider themselves to be incapable of doing proper economic work. We can make broad claims about cuts and austerity, but ask a leftist to analyze the consequences of a change in eurozone bank collateral and most are lost. Thus, the third major explanation of the lack of economics in leftist circles is that we don’t have the institutional basis to grapple with the nuance and details of modern economies. This, to put it simply, is a major failing. And moreover, it’s one that can’t be solved overnight.

So there is a massive gap at the heart of contemporary leftism, yet there is also space for collaboration. There are pockets of interesting work being done. From modern monetary theory to complexity economics to ecological economics to Parecon, along with people like David Graeber, Doug Henwood and Paul Mason, trajectories of innovative thought are being launched. But in the current conjunction, leftists in general need to be literate about economic matters and stop surrendering this ground to the scholars of capitalist realism.

[1] I should be clear from the start, the ‘left’ referred to here excludes the broadly Keynesian supporters ranging from Paul Krugman to Christina Romer to Matthew Yglesias. Instead, the term ‘left’ here indexes a mostly non-Keynesian group of thinkers – typically with Marxist tendencies, but more generally interested in post-capitalism.

Enlightening and brilliant article, not only a very good account of ”what;s wrong with the left” but also a good platform to build on post-capitalist alternatives. thanks Mr. Srnicek

LikeLike

One answer, in the context of US politics but broadly applicable, can be found here: http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2010/09/you-vs-corporations/

In a broader context the words of Wolfgang Sachs ring true: “The world will no longer be divided by the ideologies of ‘left’ & ‘right,’ but by those who accept ecological limits and those who don’t.”

Another point to consider is that there are dozens of radical schools of alternative economics competing for attention, from those espoused by eminent academics (Ecological Economics, Modern Money Theory) to the more drooling reactionary stuff from anarchists, libertarians and other extremists. That you haven’t heard of these is rather telling of your own insight into politics. You have only mentioned three alternatives to the neoliberal economic paradigm and these are flavours of neoclassical economics. In the words of Professor Steve Keen “here’s a simple guide for the public: Anything the vast majority of economists believe is likely to be wrong.”

Maybe you should cast you research net a bit further a field before you next sit down to write one of these silly little navel-gazing exercises.

LikeLike

Let me quote myself in response: “Admittedly, the left is not entirely devoid of high-level economic theorizing. Rather, the more specific problem is that those few who do such work are a relatively tiny minority and are typically marginalized within the leftist scene.”

As for missing other theories – I guess I could have gone through and listed every leftist economist and leftist economic theory I know of, but that would have been pretty pedantic, no?

LikeLike

You had no need to go through and list “every leftist economist and leftist economic theory [you] know of”. I’ve already observed that, as with most economic theories, the great majority originate from nutters and frothing loons with little or no insight. Steve Keen’s quote should have really driven this home but I can’t blame you for missing that, seeing as he’s an economist warning against heeding the words of economists.

No, instead what you could have done, in your role as commentator, was to research some of the more plausible alternative economic theories and ideologies and discussed their relevance and potential as solutions to our current economic crisis. You have utterly failed in that goal, which is why the subtext of my comments here are that you are a mindless fucktard. You’ve successfully identified self-censorship in “lefty” economics commentary and then gone on to censor yourself in exactly that manner whilst commenting on “lefty” economics. Its just so deliciously Kafakaesque.

LikeLike

it should be noted that “punk science” states on his blog that he is “trolling this post” and because of this he “rules”. i would suggest ignoring him although that is probably easily discernible just from the moronic content of his replies.

LikeLike

Haha, thanks for pointing out that post Nathan. And yeah, I broke the first rule of blogging: don’t feed the trolls.

LikeLike

A provocative post, and in a good way. My sense is that there is some variation here, and that there’s a deeper leftist engagement with economics in fields like development studies and international political economy within IR, but your generalised diagnosis certainly seems right to me.

That said, I think there’s a significant problem lurking here, which has to do with some differences between ‘left’ and ‘right’. Our objection is that there isn’t enough ‘constructive’ economics on the left, but it seems that this is vanishingly rare on the right too, presumably because the dominant economic agenda of the right is more easily translated into political terms (turn back existing achievements of social democracy, free up capital from ‘unnecessary’ restrictions) in a way that just isn’t paralleled in the agenda being hoped for on behalf of the left. Krugman, Stiglitz, Ha-Joon Chang et al. do seem to represent the leftist variant on this.

In other words, it’s not that the centre and the right ‘do’ economics with a gusto that the left lacks, but that the notion of a ‘leftist economics’ is by definition more comprehensive, more critical, and therefore more difficult to achieve in the first place.

I know that there are concrete coalitions which have worked towards neoliberalism over the decades, but it still strikes me that this is a more narrow technical application of economic theory than the wholesale rethinking your post seems to envision. That doesn’t undo the call for a greater engagement with economics, but it does indicate caution. Capitalism wasn’t brought about by a selection of committed theorists carefully thinking through the options – it was theorised by people who were observing a conjunction of forces pushing things in a certain way before their eyes. I see no reason to think that any move away from, or heavy modification, of capitalism could happen via a better understanding of economics since, as you seem to indicate, the complex combination of social forces prevents any such vanguardist control.

LikeLike

Yeah, that’s a good point about some leftist economics being done in IPE – that seems to be one of the remaining bastions for it.

Not sure that the right are lacking in constructive economics though. Rather, I think your point about leftists having to take a more comprehensive approach is the reason why it’s easier for those in the center or right to construct proper economic visions. When you’ve abstracted away from class, society (except families!), power, etc., it becomes much easier to make arguments about how to most efficiently allocate resources.

Entirely agree with your points about how such ideas actually get implemented, though I think there can be a more systematic vision in establishing new economies. Alex Andrews is the expert here, but I’m pretty sure neoliberalism is the prime example of such a case where a committed group of people had broadly systemic notions of what the ideal economy should look like and went about implementing that. Admittedly this was in piecemeal fashion, and only where possible, but still with an eye to the end goal.

I’m just not sure how we could think of making large changes to existing economies without having some relatively expert idea of how they function. There can (and should) be both some level of intellectualism about thinking through the economic consequences of actions, as well as a spirit of making-do with whatever the contingent circumstances present. The old theory and practice divide!

LikeLike

I should have been clearer on neoliberalism. What I mean is that the standard for a leftist economics appears to be how it can imagine a system which is non- or anti-capitalist in some deep sense, whether that goes by terms like ‘post-scarcity’, ‘ecological’, ‘anarchist’, ‘communist’ or whatever (less dramatic agendas seem excluded by your footnote). Now, what the Chicago School is usually held to have implemented in Chile is an example of a committed group putting into place an agenda for a particular kind of economy, but it still seems that this is less than what you’re asking for. After all, they were dealing with a single country in the context of an overwhelmingly capitalist world economy – a country that had embarked on a decade-long project of nationalisation and strong social democracy – and were trying to turn it in a particular direction, but a direction that still had a strong basis in previous practice, in patterns adopted elsewhere, and on principles updated from long-established ones in the history of economic thought.

That seems like a difficult project, but is still much easier than conceptualising (never mind implementing) a global post-capitalist economic system.

I take the point on abstraction, but what I meant by ‘comprehensive’ was that ‘leftism’ of this ilk envisions the transformation of a wide range of social relations, whereas discovering the principles that make an existing system work so as to sufficiently optimise it seems less concerned with comprehensive transformation when it comes to policy, imagination, utopia and the like.

LikeLike

Full disclosure, I’m coming at this from a Marxist perspective. I don’t think it’s fair to say that Marxists don’t look past the Revolution…rather, that Marxism as a theory is recognized to have limitations akin to the singularities in mathematical physics — after all, how can a theory whose formalism is the actions of competing classes be used to predict the social dynamics of an epoch without classes?

That said, my own inclination is to think there is some predictive power in even orthodox Marxism past the point of socialist revolution, and I’ve toyed with seeing if Marx-like models can accurately predict Stalinism & degeneration of workers’ states without relying on explanations like the isolation of Russia.

LikeLike

I swear I’ve had this same debate with a friend recently, and we came to the conclusion that we’re simply not sure whether Marxism proper offers any way to extrapolate from the dynamics of capitalism to a post-capitalist economy. Exactly like you say, it’s a matter of singularities within the theory.

The use of Marx-like models to try and answer this question sounds fascinating though! I’ve only had vague thoughts about doing similar stuff, but it’s really encouraging to hear others are actually experimenting with this.

LikeLike

‘That said, my own inclination is to think there is some predictive power in even orthodox Marxism past the point of socialist revolution, and I’ve toyed with seeing if Marx-like models can accurately predict Stalinism & degeneration of workers’ states without relying on explanations like the isolation of Russia.’

Some of the state capitalist analysis of the old socialist states go towards this, don’t they? CLR James wrote on the possibility of statalized capitalism and class struggle in the soviet workplace (the ‘vertical’ side of capitalism), and then the IS school’s consideration of the international politco-military struggle in the cold war as being the ‘form of competition’ compelling capitalist conduct internally (a sort of ‘horizontal’ complement to James).

As long as one does’t take these analyses to be ways of beautiful soul ‘quarantining’ actual socialisms but rather as outlining potentials for failure in transition, then perhaps in a negative way they can contribute to such a theorising. The focus would perhaps be on workers’ situational capacity for effective control.

I’d suggest a materialism-accented Gramsci could also be useful – the practical solution in transition to the big problems of hegemony, such as how to incorporate and transcend the urban – agrarian divide, would set the pattern for whatever dynamic the future society had.

Perhaps part of the problem is that the view of socialism as entailing more conscious control and democracy implies a much heavier use of natural language and the ‘linguistification’ of previously pseudo-mechanical economic processes.

Decision points would be sites for the suspension of activity to allow discoursing on consequences, which interposes a self-conscious labour of interpretation into what would previously have been ‘computable’ by price signals, accounting and the exclusion of arbitrarily selected ‘externalities’ from analysis. Perhaps this precludes the identification of a complex of law-like regularities in a communist mode of production analogous to those found by Marx in capital.

Though language does have its grammar (here I will stop due to my ignorance of linguistics).

LikeLike

(Though actually, perhaps that interpretative work is already included to an extent in capitalism behind the scenes – such as the work of actuaries and the ubiquitous use of ‘risk’)

LikeLike

Monthly Review has been doing good economic work for many years. I doubt there is a better magazine for linking environmental crises and economics. And we were far ahead of the curve in terms of an analysis that fits the current situation pretty well. Our Press publishes plenty of left economic analysis too. Michael Yates, Associate Editor and Editorial Director of Monthly Review Press.

LikeLike

Good point Michael. Monthly Review has been keeping leftist economic thought alive for decades now, and John Bellamy Foster’s work has been some of the best in trying to merge ecological economics with Marxist economics. In my anecdotal experience though, it’s not widely read enough amongst UK leftists. (I can’t speak for the US situation.) Which is the ultimate point I’m trying to get at – that while there are pockets of interesting work being done, the tendency amongst most leftists seems to be to have only a basic grasp of economics. In other words, it’d be great if more people were arguing and debating over Monthly Review articles!

LikeLike

Part of the problem might be “the Left” and the other part “Economics.”. Both have a predilection for blackboard exercises and rhetorical flourishes that don’t have a lot of traction in an actual crisis. A bird’s eye view is exhilarating and can provide a plethora of clues about where to start one’s analysis but ultimately one has to come back to ground.

What is it about people’s daily lives as they go about making a living? That’s the question at the core, not “how can we ideally make the economy work better?” or even “what’s really happening with all those numbers?” Those other questions become important along the way in telling the story and refining the analysis but strategies and solutions don’t come from the “numbers” or “the big picture”.

My own theorizing didn’t come from juggling numbers or reading Hilferding. It came from being unemployed and thinking hard about what that meant — the daily search for a job, relationships with my family, friends and col

leagues, the value given (or not) to my views on what needed to be done. The most important lesson I learned was that what I had to say, as an unemployed person, was the very last thing that most “experts” would consent to listen to. That included experts “on the left,” Fortunately there were exceptions.

What I did over the next 16 years was research and document the systematic exclusion of the voice of the unemployed from the discourse of economics about unemployment. I unraveled the history of the taboo and in doing so demystified its mystery. 2011 is the bicentennial of the Luddite uprisings. Those events were about the unemployed and exploited workers resisting their unemployment and exploitation. But the label “Luddite” has come to be used to brand people as ignorant and superstitious. Hence, if you are unemployed and you speak out against unemployment, you are ignorant and superstitious. Shut up and let the “experts” tell you what is good for you.

To make a long story short, I’ve parlayed my research into a book manuscript, Jobs, Liberty and the Bottom Line, It’s not “Left” and it’s not “Economics”. It’s sort of whats left out of economics.

LikeLike

Pingback: Irish Left Review · Has the Left given up on Economics?

i think this is a great post. full disclosure, i’m probably closest (although not fully in line) with a minskyian/chartalist (as you say, “modern monetary theory” although i hate that term. anything espoused by plato and ancient chinese thinkers among others i refuse to call modern) point of view. however, getting most activist left wing people i know to understand that sentence would take a whole lot of background. economics seminars that express multiple, conflicting point of views are badly needed on the left.

LikeLike

I’m only an amateur in these matters, but I always took it that the ‘modern’ aspect of MMT essentially referred to the fiat currency system. Which, so far as I know, is quite modern in historical terms. I’d be interested to hear how MMT traces back to Plato and ancient Chinese thought though!

LikeLike

i should be careful here. I’ve looked back and realized that the book i’m reading cites schumpeter’s history of economic analysis (http://books.google.com/books/about/History_of_economic_analysis.html?id=pTylUAXE-toC) as the source for plato being a cartalist. the book i’m reading right now happens to be on money and monetary policy in medieval (and earlier) china. http://books.google.com/books/about/Fountain_of_fortune.html?id=DNlv4f9tV_AC . it is very clear from china’s money creation myth and other direct quotes that cartalism was the dominant monetary theory for centuries in china, probably owing to the sheer size of china itself. i have however, not read plato in the original and will be sure to do so before i cite him as a cartalist thinker even though it is widely accepted in the literature. see page 25 of fountain of fortune for example.

LikeLike

Right, there is nothing modern about chartal money. Dr. Tcherneva puts all of what she knows about it here (The Nature, Origins and Role of Money: Broad and Specific

Propositions and Their Implications for Policy http://www.cfeps.org/pubs/wp-pdf/WP46-Tcherneva.pdf)

LikeLike

Thanks for the MMT shout out, if people would like to learn more about it, this PDF would be a great starting point: http://moslereconomics.com/wp-content/powerpoints/7DIF.pdf

and these fine blogs:

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/

http://neweconomicperspectives.blogspot.com/

http://www.winterspeak.com/

http://moslereconomics.com/

http://heteconomist.com/

LikeLike

Thanks for the links! I’ve found this to be a good introduction to MMT too (including the videos): http://pragcap.com/resources/understanding-modern-monetary-system

LikeLike

Ehh, careful. The writer of Pragcap never understood many finer points about MMT. It’s best to learn it straight from the creators themselves.

LikeLike

Pingback: Has the Left given up on Economics? – media and arts technology

Pablo’s point about the ‘right’ having a slightly easier time of it, I think is true. For a start, the ‘right’ conceives of economics as subordinate to a set of political ideas about individual autonomy. Sometimes they frame this as human nature, which seeks to obscure the political ideology at play, but it is there for all of them. For the ‘left’ I think there is a more fragmented set of claims about the underlying political ‘ontology’, much as I hate that word. Class, ecology, etc., you provide a long enough list to make the point very well. The left in this sense is an assemblage of alternatives, whereas the right is more coherent.

Secondly, there has been a tendency to confuse the relationship between economics and politics. For some ‘leftists’ economics has been an imaginarium of political solutions, and to some extent this meant turning to economics to produce fundamentally political outcomes, which would indicate a retreat from politics, perhaps in the 1980s, when it proved difficult to win power on the back of alternative models of social organisation than one based on a high degree of individual autonomy?

Therefore when you ask the question of whether the ‘left’ has abandoned economics, I would suggest the possibility that economics has abandoned the left, because the basic idea of individual autonomy (property, contract etc.) remains hegemonic. Which is why I also think that the current economic crisis is a crisis for the left, more than for the right. It’s actually a crisis for everyone, but some on the right can at least say ‘I told you so’ even if solving the problem is no easier as a consequence. (I don’t think that the crisis is a ‘crisis of capitalism’ which I have heard repeatedly, but is merely the logic of capitalism asserting itself after years of abuse.)

The deeper problem for the left, (and to declare an interest, that makes is not my problem exactly) as far as I see it, is to successfully articulate political alternatives, not economic alternatives. I’m sure this is much harder to do, but economics flows from politics, not the other way around (clearly not everyone will agree with this, but I think as long as an ideology of individual autonomy dominates public discourse, it remains an obstacle of persuasion for those who think differently). The abolition of property requires a political critique, not a demonstration of sub-optimal allocative efficiency. The latter might be a part of the former, but people have to be persuaded of a better alternative, and the example of leftist revolutions – or their consequences – does not yet provide much inspiration. (except perhaps those few lines of Wordsworth ‘to be young … etc.’ but even this has to be seen as a critique of revolutionary sentiments).

Just one last point, when the left see the current economic crisis as ‘an opportunity’ it implies that people will be looking for new economic theories. I don’t think so. The left will not capitalise on this current malaise with new forms of economic theorising, but by actually winning an argument about political alternatives.

And a further last point, I think you are absolutely right to say that the left need to be more proficient at making economic arguments. But I think this is true for everyone. Economics is not actually that complicated, its technical mystification has – as far as I am concerned – come about because economists wanted to mask political objectives with the authority of technical expertise. Obviously I think economics – as an academic discipline – has long been dominated by the left in one form or another.

LikeLike

Hahahaaa, yes. Because I’m trolling that makes me wrong. Logic FAIL.

LikeLike

i never said that. it does point to the fact however, that interacting with you is probably not worth the effort since your goal isn’t greater understanding, but greater annoyance.

LikeLike

Don’t you think people can evaluate themselves the benefits of interacting with a self-declared troll? And I don’t aim to annoy, that’s not what I understand as “trolling”: “In Internet slang, a troll is someone who posts inflammatory,[2] extraneous, or off-topic messages in an online community” – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Troll_(Internet)

You can’t accuse me of going off-topic. I do accept that it is highly likely that you will be annoyed by my communication, but I flatter myself to think that that’s more because I have presented an utterly devastating critique highlighting the intrinsic contradictions of this article than my scornful and inflammatory style. Again, I think people can decide that for themselves. Personally I see my role more as a therapist trying to tease the threads of reality out from your heavily propagandised thoughts. You may not enjoy the therapy but, if you genuinely adhere to the broadly humanist principles most self-declared “lefties” espouse, you definitely need it to aid in your quest help our civilisation survive and flourish

If you have an issue with the rationale of my comments above then why don’t you share them with us here? However appropriate your ad hominems are, they remain a logical fallacy and contribute nothing to the issue.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Red Tower or Weirding Wall street « Naught Thought

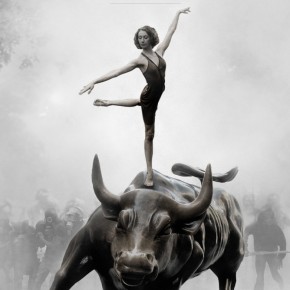

One of the most glaring problems with the supporters of Occupy Wall Street and its copycat successors is that they suffer from a woefully inadequate understanding of the capitalist social formation — its dynamics, its (spatial) globality, its (temporal) modernity. They equate anti-capitalism with simple anti-Americanism, and ignore the international basis of the capitalist world economy. To some extent, they have even reified its spatial metonym in the NYSE on Wall Street. Capitalism is an inherently global phenomenon; it does not admit of localization to any single nation, city, or financial district.

Moreover, many of the more moderate protestors hold on to the erroneous belief that capitalism can be “controlled” or “corrected” through Keynesian-administrative measures: steeper taxes on the rich, more bureaucratic regulation and oversight of business practices, broader government social programs (welfare, Social Security), and projects of rebuilding infrastructure to create jobs. Moderate “progressives” dream of a return to the Clinton boom years, or better yet, a Rooseveltian new “New Deal.” All this amounts to petty reformism, which only serves to perpetuate the global capitalist order rather than to overcome it. They fail to see the same thing that the libertarians in the Tea Party are blind to: laissez-faire economics is not essential to capitalism. State-interventionist capitalism is just as capitalist as free-market capitalism.

Nevertheless, though Occupy Wall Street and the Occupy [insert location here] in general still contains many problematic aspects, it nevertheless presents an opportunity for the Left to engage with some of the nascent anti-capitalist sentiment taking shape there. So far it has been successful in enlisting the support of a number of leftish celebrities, prominent unions, and young activists, and has received a lot of media coverage. Hopefully, the demonstrations will lead to a general radicalization of the participants’ politics, and a commitment to the longer-term project of social emancipation.

To this end, I have written up a rather pointed Marxist analysis of the OWS movement so far that you might find interesting:

“Reflections on Occupy Wall Street: What It Represents, Its Prospects, and Its Deficiencies”

THE LEFT IS DEAD! LONG LIVE THE LEFT!

LikeLike

Thanks for a really interesting post. Not sure, I understood it all, certainly not all the comments.

I read it because I had been thinking, rather more parochially, that the British Labour party (not identical with the “left”) seems to me to lack a coherent approach to the economic situation of the 21st century post-industrial worker. To be specific, the concept of the entrepreneur or contract worker seems to fall outside of its imagination, leaving the entrepreneur to be seen as purely a creature of a distasteful right.

The result is that its only model seems to be one employer-employee, which was fine when most labour was carried out in large factories, but is not helpful in an economy when relationships between workers and clients are more fluid and have more actors. This limited thinking applies not only to how it thinks about workers, but also the unemployed. For example, in a difficult market, when does a freelancer decide that she is unemployed? That is a going to be a lot less clear cut than redundancy form an employer. Yet this is precisely the model the party defends rather than thinking about its reform for a reality in which individuals may have multiple sources of income one week, none the following and different source the following.

I am not sure if this is what you mean by the left having given up on economics, but certainly it does seem to be something which they don’t think about, reacting only to the deminishment of old securities which are themselves in dire need of reform.

LikeLike

Pingback: On the stalled project of Marxian economics « Necessary Agitation

Pingback: Cultural Turns and Dead Ends in the Academy « Chaos and Governance

Pnkscnc hs fckd y mgs rght p!

Psdntllctl mppts.

LikeLike

Henceforth, all naked trolling and/or rampant abuse will be disemvoweled thusly.

LikeLike

Love the disemvoweling idea, just so long as we leave punkscience’s amazing self-delusions alone!

LikeLike

Fckng WRD!

ll y psdlft cnts cn lck m.

LikeLike

Your analysis of the Marxists may apply to Orthodox Marxists for the most part, but there are schools and variants of Marxism, and not to forget, Anarchism (not the lifestylist/individualist variant) who are not economic reductionists in the late Marxist sense but do stress democratic process. The task of a free society would have to overcome accumulation caused by the market system by democratically redistributing resources. Though there is a significant and excessive focus on politics within the far left which has created a climate of political cliqueism often manifested in divisive party-building vanguardism and de-theoretised lifestylist fun-fests.

What you have touched on lightly in your article is that good portions of the Left nowadays are excessively focused on identity politics, usually a liberal variation based on excessive focus on decontextualised choice within some existing institutions, instead of the social environment and dominant social philosophy which creates relations of domination and vilification often adhered to subconsciously by those they privilege (the social element being what radicals stress). While women’s rights and queer rights are important they are still politics confined to certain spheres, feminism does touch on economic arrangements to a certain degree – but this is often the problem, economics comes tangentially to a political understanding.

LikeLike

The problem as I see it is that the economists work within the system, whilst the politicians do as they see fit. New economic systems may be in poor stock, but the ones that exist have been ignored due to a mainstream mindset. If the left is ever going challenge the capitalist propaganda they need to influence social change before they can construct better systems.

LikeLike

I also don’t believe in a magical change that will come from revolutionary new system. It would be more likely that the current system would be modified to the better following political reform. The attitude of society has to be shifted from conservatism to a more scientific and egalitarian approach.

LikeLike

Pingback: Links 10/15/17 - Daily Economic Buzz

Pingback: Onapologetisch pleidooi voor een politiek van de vooruitgang | mondig